Meaningful Returns

For activists frustrated with the pace of change in the physical world, NFTs are opening up new ways of thinking about the digital repatriation of looted African artifacts.

When Mitchell Chan asked me to write about my favorite games for Outland, I said yes immediately. I like games. I like Mitchell. I like Outland. “Sure,” I said, “I would love to contribute.” But when I sat down to write, it wasn’t as easy as it had seemed. There was an immediate problem: in order to write about my favorite games, I first needed to know what a game is. Unfortunately, I realized, I have no idea.

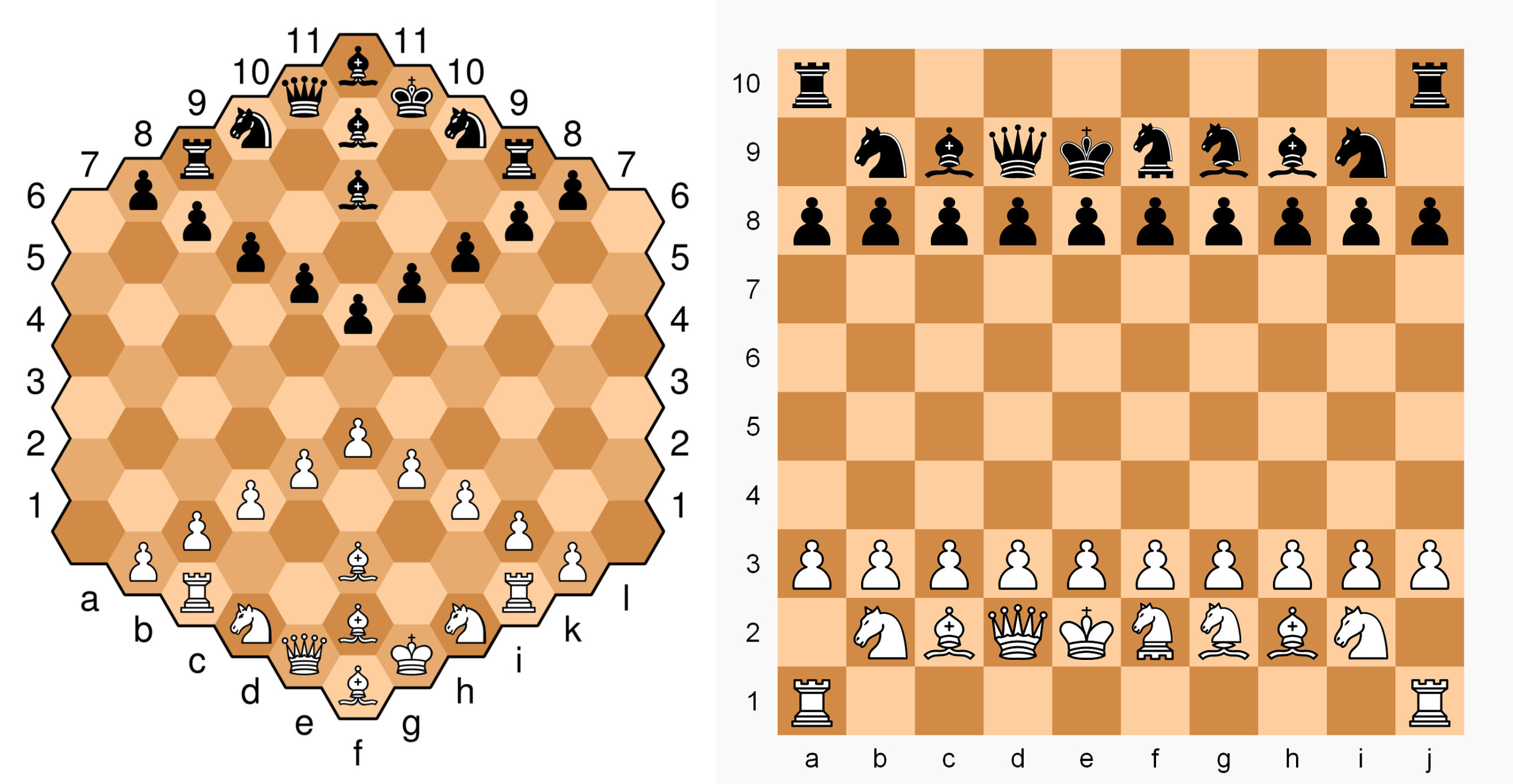

Yes, sometimes it seems obvious: a video game, a board game, a tabletop, a LARP. Many of these things are easily called games. But when it comes time to chisel the definition into the stone tablet and carry it down the mountain, I confess to you that I do not know where to start. Like so many things, I find, the more I look at the question the less I know. What does Truth or Dare have in common with Death Stranding (2019)? What does The Sims, first released in 2000, have in common with the ancient game of Go? Can something like “a game” ever be usefully and canonically defined?

What does Truth or Dare have in common with Death Stranding?

I’m not the first person to admit uncertainty. In his posthumously published Philosophical Investigations (1953), Wittgenstein considered the problem of defining what a game is and abandoned it as unsolvable. He wrote, “For how is the concept of a game bounded? What still counts as a game and what no longer does? Can you give the boundary? No.” He then uses the impossibility of defining a game as an exercise in questioning the task of creating precise definitions in general. “Is an indistinct photograph a picture of a person at all? Is it even always an advantage to replace an indistinct picture by a sharp one? Isn’t the indistinct one often exactly what we need?”

Of course, not everyone agreed; in The Grasshopper: Games, Life and Utopia (1978), Bernard Suits responded to Wittgenstein by offering a precise definition of games. First, according to Suits, games require bringing about a specific state—i.e., the ball must go through the hoop. Second, they have rules that prevent that state from being achieved by the most efficient means—i.e., you can’t carry the ball to the other side of the court, only dribble it. And finally, they are undertaken voluntarily. The book is structured as a series of Socratic dialogues between the grasshopper of Aesop’s fable, who spent all his time playing games and now must die because he has no food prepared for winter, and his disciples. Besides offering the definitional criteria above, the grasshopper argues that his choice—to play games all summer even though he must now die—is not only good, it is the supreme good.

Following the grasshopper’s definition, many things we don’t often call games must be included, such as mountain climbing. Many things often called games don’t fit. But over the years, practitioners have contributed other definitions and criteria for games. One famous example is the concept of a magic circle: a space, which a player enters and exits, constituting the reality of the game. This was paraphrased nicely by Seth Killian, a game designer who has worked on franchises like Street Fighter and Fortnite, during Summer of Protocols, a research fellowship we were both part of last year: “The game is the ability to exit.”

But, again, I’m not sure all games have a magic circle. What about The Game? The object of this thought experiment is to avoid thinking about The Game. Everyone who has learned about The Game is playing it. There is no way to quit or stop playing The Game. A person loses every time they think about The Game, and every time they lose they are required to announce it—for example by saying aloud, “I just lost the game.” Of course it’s impossible to enforce the no-quitting rule, and quitting is fairly easy (just don’t announce when you lose). But for those playing—still within the magic circle of the game—to quit is perhaps to cheat, or to dwell perpetually in the state of losing. There are conflicting realities existing on top of one another, like Photoshop layers. In one reality, there is no exit. Who is to say who’s right? Related in both scope and exitlessness is Le Grand Jeu, an existential proposal from Roger Gilbert-Lecomte and René Daumal, contemporaries of the surrealists. “It is played only once. We wish to play it every moment of our lives,” wrote Gilbert-Lecomte in 1928. “It is a case of ‘loser wins,’ since the aim is to lose oneself. And we want to win. Yet the Le Grand Jeu is a game of chance, that is to say, of skill, or better still ‘grace’: the grace of God, and the grace of action.” The game is, of course, life itself.

As another example of a game with no boundary or possibility of exit, let me tell you about Life and Death Pong. Its real name is Type 1 Diabetes, as assisted by a continuous glucose monitor, which is a small device worn usually on the arm that sends real-time updates about your blood sugar level to your phone. I can’t say that it’s particularly fun, but I play Life and Death Pong every day. The object of the game is to keep the ping pong ball in the green zone. The body of a person without diabetes would do this effortlessly, by producing insulin in response to meals eaten. For a person with Type 1 or some other insulin-requiring form of diabetes, it’s not so simple. They have to operate both paddles of the pong games themselves, using the tools of insulin, food, and exercise—all applied in the right combinations at the right times—to keep the ball in line. If the ball goes too high, the chance of long-term health complications increases. The low line? Almost immediate malaise and distress. In severe situations, it can cause seizures, unconsciousness, coma, and death. Keeping the ball in the green zone is difficult, but not impossible. A skilled and attentive player can sometimes do it for an entire day. I rarely manage myself. But every night, after game over, I wake up and start again. Just kidding! You have to play all night too. To stop playing is to die. The seriousness of the situation doesn’t disqualify it from being a game: There are plenty of games where death is a possible consequence, such as Russian Roulette, or gladiatorial combat. And fictional ones, like Squid Game (2021) and Battle Royale (2000).

Of course, Life and Death Pong didn’t start as a game—it’s an illness. And the designers of the tech did not intend to design a game, but it’s still hard to deny the game-like quality of its mechanisms and interface. Does a game need a creator? (Does a world?) Life and Death Pong’s lack of anything like a magic circle, its high stakes, and its unintentional creation could disqualify it from gamehood or it could disqualify those as important definitional criteria: you choose. I certainly don’t know. But perhaps that is not the interesting question. Instead, you could ask: What we learn about games when we look at them alongside medical tech? What do we learn about medical tech when we look at it alongside games? Medical tech is hardly the only such thing we could compare to games: One could scaffold a parallel about stock trading, social media posting, the NFT market, and most self-tracking endeavors (as Chan himself does in his 2023 game, Boys of Summer).

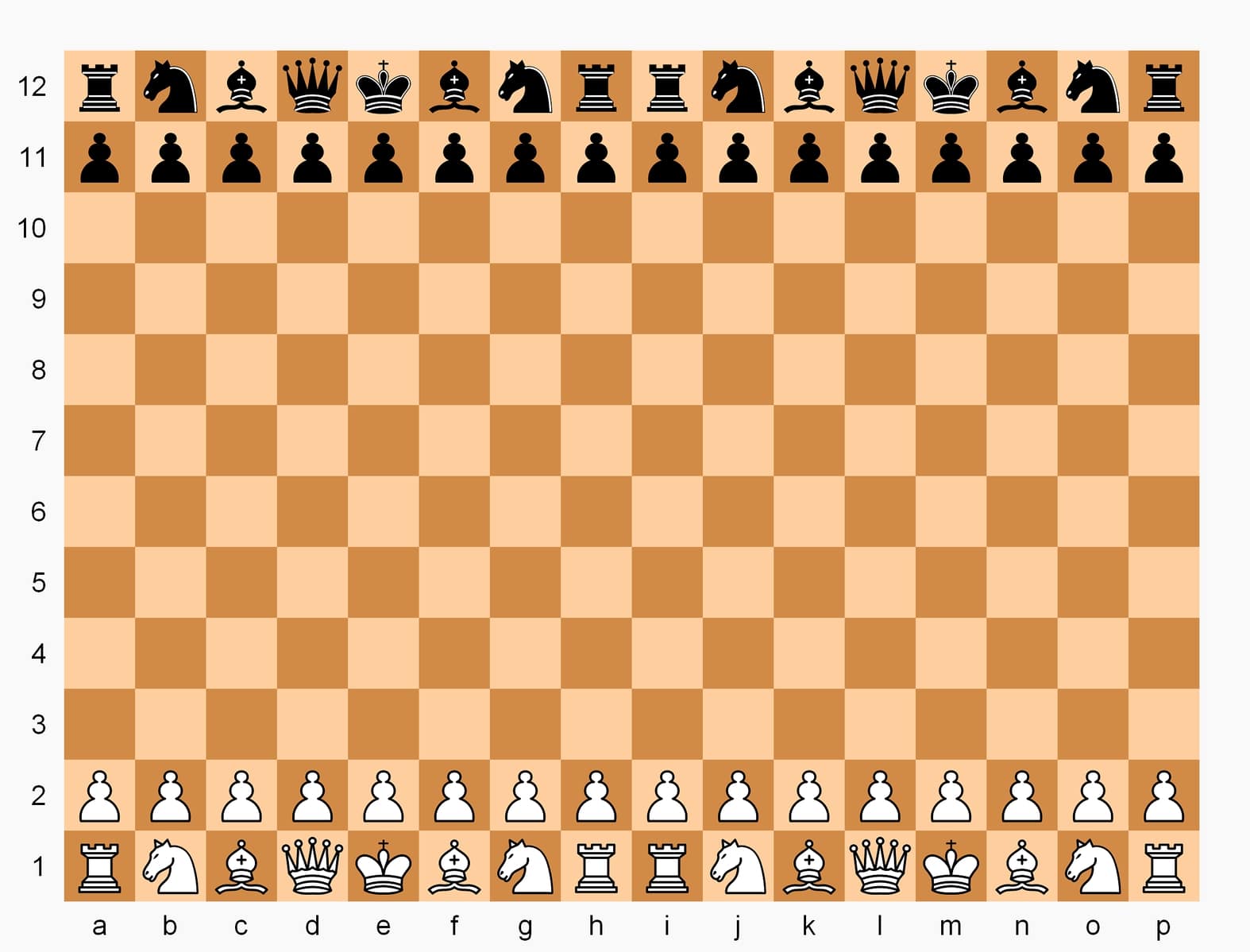

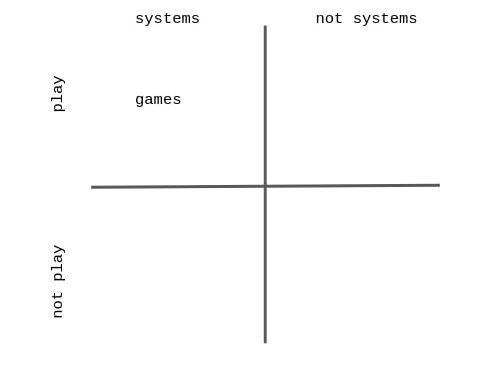

I have sometimes defined games as existing at the intersection of systems and play—but I do this usually to expand the matrix, following the model of Rosalind Krauss in her 1979 essay “Sculpture in the Expanded Field.” Krauss characterizes sculpture as that which is not-landscape and not-architecture in order to map the logical space around sculpture. All these terms or concepts, for her, characterize the “expanded field” and are related. This leads to a reflection on the collapse of medium-specificity: “[T]he logic of the space of postmodernist practice is no longer organized around the definition of a given medium on the grounds of material, or, for that matter, the perception of material. It is organized instead through the universe of terms that are felt to be in opposition within a cultural situation.” This is useful for the artist working with games today, in the sense that it can free them from stringency around the concept of “games.” Do artists’ games work as games—or are they too strange, non-linear, unfun, essentially not pleasing to a player? Placing these creations instead in the expanded field renders these concerns moot. It is also a source of new possible insights: what other concepts are near games, situated within the same matrix of logical structures we use to understand games? How do we understand both games, and other expanded field mediums better, when we focus on their relatedness?

The truth is that I am not that interested in having a definition of a game at all. I’m here for the metagame, what Wittgenstein calls “the language-game with the word ‘game.’” Look, the game-essence of 52 Card Pickup exists in its absurd proposal that picking up every card in the scattered deck could be a game. It’s a parallel gesture to the canonical one of Duchamp, in which a urinal was transubstantiated into art through its presentation in an exhibition. How can we interact with something differently when we see it as a game? And so my endgame is not to admit that I don’t know what a game is, but that I do not want to know. I am not a grasshopper. Or I am a different type of grasshopper, one more interested in questioning what a game is than in having an answer. Or am I the grasshopper after all, because isn’t such questioning exactly what the grasshopper himself is doing all through Suits’s book, as he works out the definition in dialogues? He dies when he has finished.

I’m here for the metagame, what Wittgenstein calls “the language-game with the word ‘game.’”

One of my favorite games doesn’t even exist, as far as I know—at least nothing I’ve found online matches the way I remember it. It’s the final Pac-Man level that I dreamed as a child, in one of those dreams so convincing you believe for years that it really happened. There I am, in my grandpa’s basement at an old desktop computer. I’ve been playing Pac-Man, and I’m really good. Good the way only a seven- or eight-year-old kid who has done nothing but play Pac-Man for the last several hours can be: running from the ghosts, gobbling dots, mashing on the arrow keys of a gray mechanical keyboard. When I reach the last normal level, the walls of the maze are red. It’s the hardest level yet, and in a cheap twist, they don’t just make you beat it once. You eat the last dot, and the red walls load again. You have to beat the hardest Pac-Man level twice. But, like I said, I’m good. My fingers are fast and ready. As I eat the last dot, the maze walls disappear and the screen goes black. Then Pac-Man appears from the side of the screen, chasing into the empty open expanse, and on the other side, there is one solitary flashing dot. That’s it. No ghosts, no points, no prizes. Nothing left between you and desire. No rules, no ending.

Sarah Friend is an artist, researcher, and software developer.