Gestures of the Generative Painter

Simulated brushstrokes have long appeared in digital art. But generative art's expressivity is less about imitating painterly gestures than devising a system to produce them.

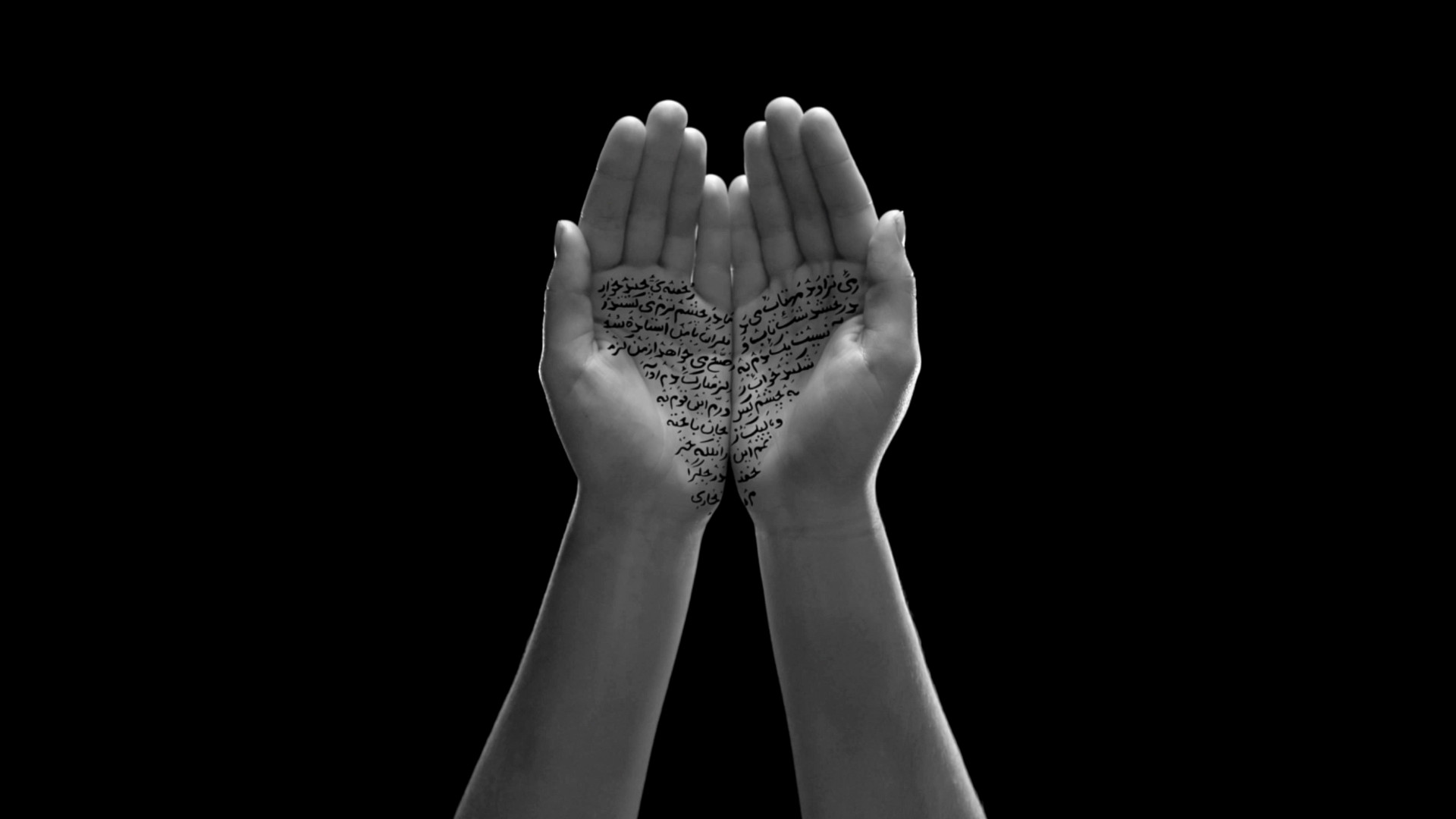

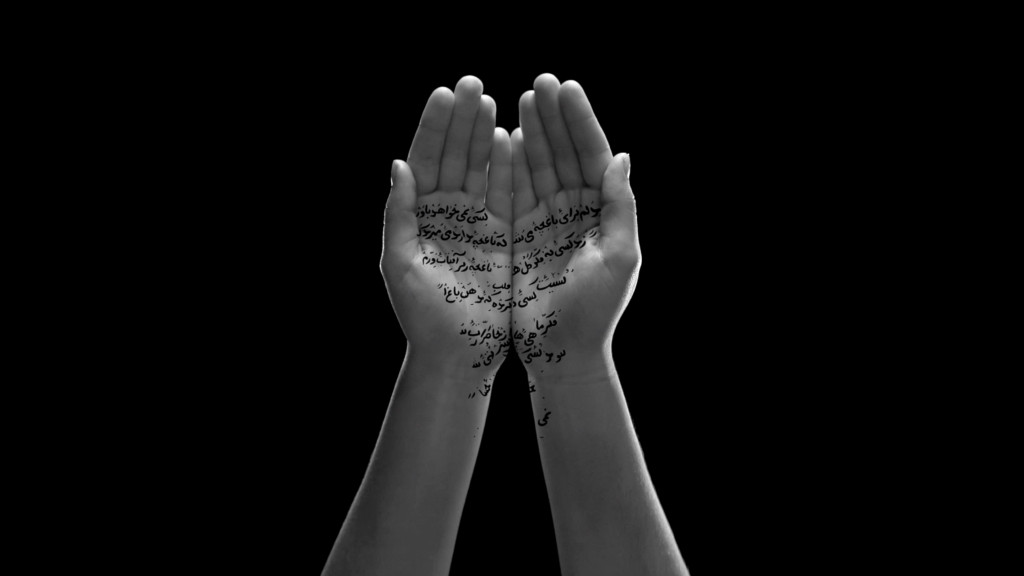

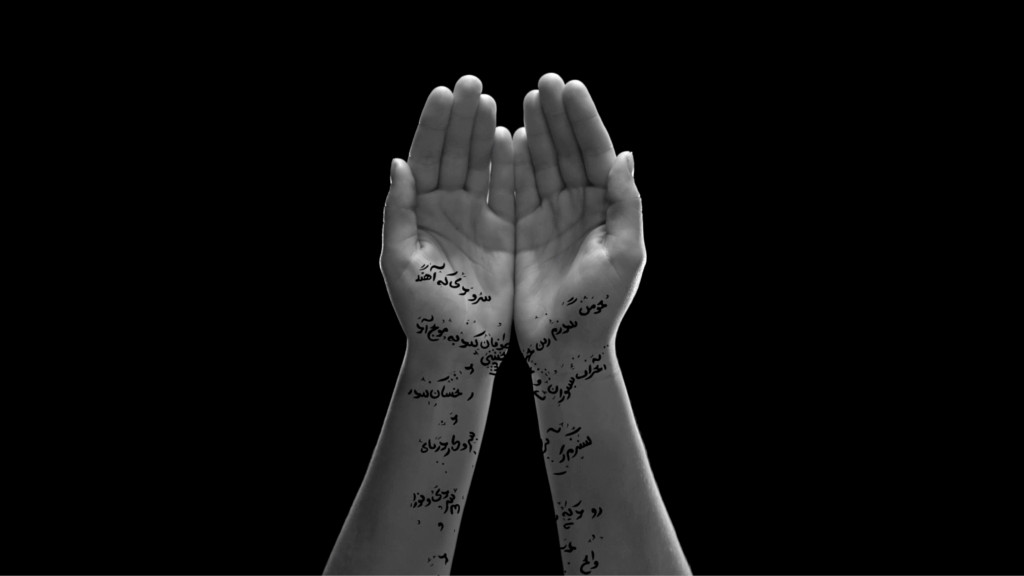

A Loss for Words (2022), a collection of short video animations by Iranian-American artist and activist Shirin Neshat, consists of ten pieces, each based on a poem by a well-known Iranian poet. The iterations are all black-and-white, showing hands held out as if in prayer. The hands open to reveal the poetry inscribed on the palms in Farsi. After a moment, the writing pours down the wrists and upper forearms, flowing past the edge of the frame. The hands close and then reopen, replenished with verse. Neshat has long made work about Iranian women’s experience of their oppressive fundamentalist regime, and these verses, cycling ad infinitum in a silent performance, evoke the act of summoning words from within the self—from thin, private air—so as to release them into a world that might not want to hear them.

A Loss for Words was released by Artwrld, an NFT platform aimed at English-speaking collectors. Nothing of the poems is translated from Farsi except the titles: “Collective Love,” “Passenger,” “Moonlight,” “Song of Acquaintance,” “I Pity the Garden,” “I Will Greet the Sun Again,” and “Ungrateful/Blasphemy” (the latter three titles are each shared by two artworks that use fragments from the same poems). Because the titles are legible to Artwrld’s core audience, they would presumably carry more importance than the untranslated Farsi verses. And yet these words feel nearly irrelevant beside the much more expressive imagery of the calligraphy moving over the skin. The tension between what is obscured and what is revealed drenches these seemingly simple offerings with urgency.

The works in A Loss for Words wield the quiet confidence of conviction because the hands, both gentle and firm in their equanimity, do not give up. The unassuming way in which they open and close, softly lit against a stark black backdrop, faintly bent, smooth in their movements, evinces the steadfast grace of giving. Even when the hands hold still, there is a sense of kindness, benevolence, and generosity. Because the gift here consists of untranslated verse, it promises nothing but a manifestation of the wish to give. It’s an exchange that, though doused with poetic language, remains nonverbal. Words here represent not speech, but the desire to speak.

Words here represent not speech, but the desire to speak.

Though the viewer can connect intimately with each individual poetic offering, the narrative of the series also operates collectively. Each iteration gains strength by evoking the reiterative actions of the entire collection. Signification is decentralized across small, personal moments of connection that, nevertheless, work together. The hands could be anyone’s, and so become everyone’s. There is power in the voices of the many, but this power is built one voice at a time.

The cyclical structure of the works also generates a sense of sacrifice, a willingness to step back to plow forward. There is no evident end or beginning—no outcome—to the movements. The hands are willing to offer their verses to the world, possibly forever. After they empty, they take their time to refill, returning to a state of meditation, as if gathering new strength before engendering more words. Poetry, that most ancient medium, which employs elements such as rhyme and recursion to convey meaning beyond the literal, is both uncontainable and self-sustaining. Neshat skillfully harnesses its power to create a meaningful exchange that challenges suppression by showing that even mute verse, by virtue of its volition to exist, speaks volumes. And this verse can be written by any hand.

Calligraphy on the body is a recurring motif in Neshat’s art. The Museum of Modern Art in New York holds a photograph from Neshat’s series “Women of Allah” (1996), regarded as her first major body of work, in which fragments from Forough Farrokhzad’s “I Pity the Garden” are drawn on a woman’s fingers. In an interview with the artist, curator Fereshteh Daftari offers an interesting insight on that work: “the writing does not follow the dictates of Islamic calligraphy. It is in the artist’s own plain handwriting.” Not only does Neshat transfer authority from the translated to the untranslated, she expresses the untranslated in her own vernacular.

In both A Loss for Words and “Women of Allah,” Neshat uses the tools at her disposal—recursion, minimalism, calligraphy—to contest subjugation, to find ways to say that which is nearly impossible to say. But because A Loss for Words consists of video animations rather than still photography, Neshat can introduce the loop. Its insistent repetition conveys a rebellious silence, comparable to the tension created by the weapons in the hands of veiled women in a number of the photographs in “Women of Allah.” Hands, verse, and compositional friction accompany Neshat’s work, creating a visual language whose mission is to give voice to the shrouded.

When a woman is compulsorily veiled, her hands are some of the only parts of her body that can be seen. Her hands can communicate in ways other parts of her body cannot. Though the gestures in A Loss for Words signal prayer, this form of prayer is detached from the temple. It is personal and primordial; there is nothing institutional about its devotion. The hands give selflessly, without expecting anything in return. The commitment with which they give of themselves can be read as an emotive tribute to the risks Iranian women take to pronounce truth—such as they are taking now, with so much at stake.

The hands give selflessly, without expecting anything in return.

The recent death of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Iranian woman, from injuries sustained while she was detained by the local morality police for improper use of the hijab, set off explosive protests, with many more individuals now feared, and presumed, dead. Coded power has been turned against the women of Iran and is being used to regulate their bodies and choices. Words have failed them, and they must take action to refuse the void generated by such failure, such as cutting their hair and daring to renounce the veil. Their cries and acts of protest, heard around the world, are prompting massive rallies of support attended by those wishing to also call out, to amplify their courage.

In A Loss for Words, Neshat shows that it is not the flag, not the banner, not the title waving loudly at the top of each page that deserves focused reading, but the work being done behind it or beneath it. And no matter how many times a palm reaches out to cover a mouth, there are other lips, other throats, determined to exert their voices, via words or via action. When violence takes the form of coerced silence, the artist finds ways to make meaning speak.

Ana María Caballero is a poet and co-founder of theVERSEverse, an NFT marketplace for poetry.

@CaballeroAnaMa