Second Nature

With a projection mapping inspired by the biomimetic architecture of Antoni Gaudí, Sofia Crespo explores how technology can be harnessed to help us connect with the natural world.

Over the last four years, Shanghai-based collective Slime Engine has created an expansive network of online and offline digital exhibitions. Founded in 2017 by former photography students Li Hanwei, Liu Shuzhen, Fang Yang, and Shan Liang, Slime Engine uses readymade imagery detached from its referents to create strange, yet familiar, frameworks for collaborative installations. The universes of Slime Engine’s works have their own laws of time and space, but are peppered with iconic skyscrapers, Lego characters, and the kinds of headlines and photos found in tabloid newspapers. Many of their projects are hosted on, and built for, the web—games and virtual environments available for free distribution and download. The first-person perspective of these participatory works, especially when users experience them in the context of exhibitions, highlights the limits of individual experience in both physical and digital artistic encounters, obliquely emphasizing the importance of collectivity.

Exhibiting in malls has become more the rule than the exception in China, but Slime Engine’s repeated engagement with these sites is more than a capitulation to a domestic trend.

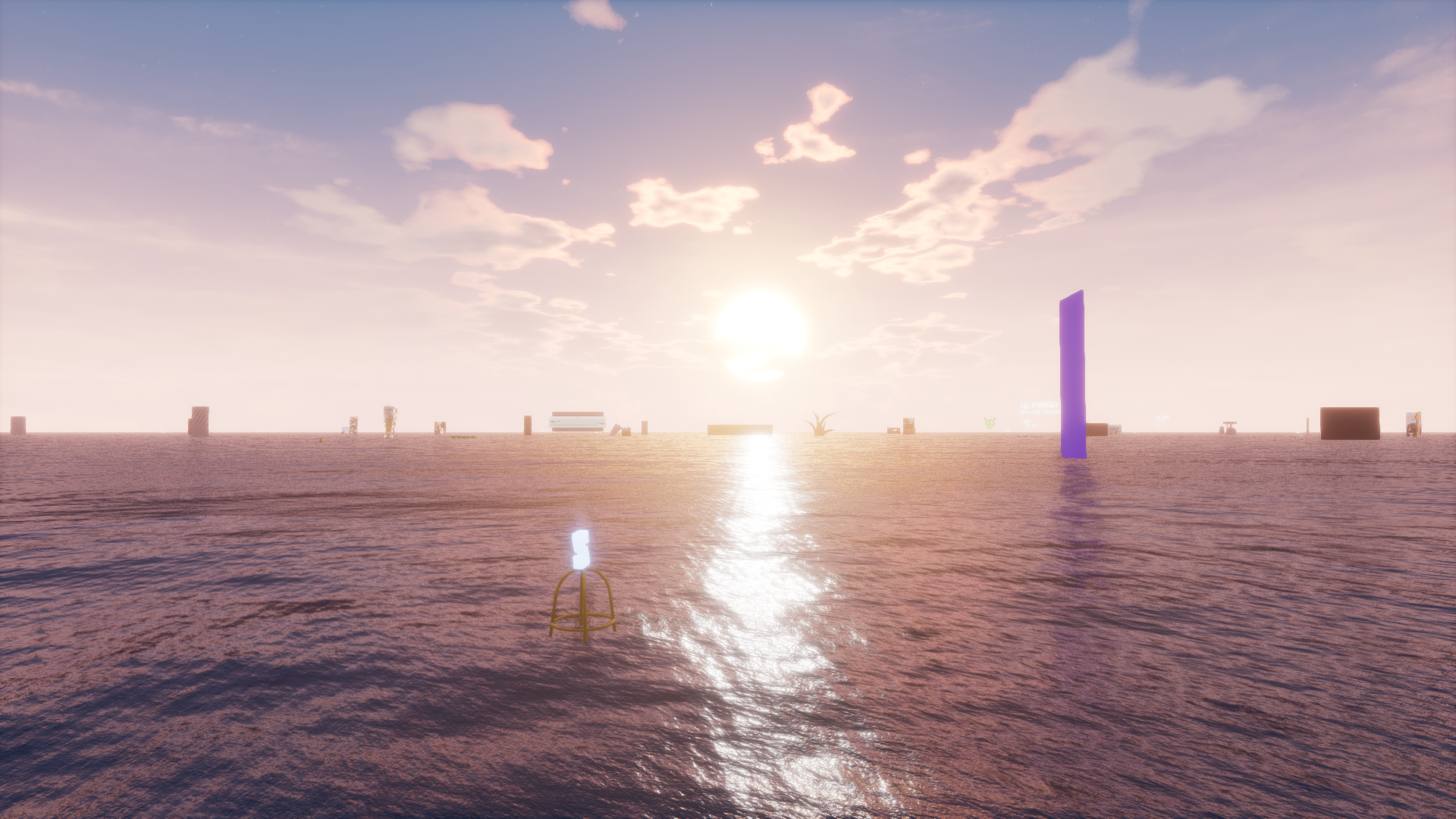

In recent years Slime Engine has expanded its exhibition activity to brick-and-mortar spaces, particularly shopping malls. These projects have highlighted the transnational properties shared by digital space and commercial architecture. Slime Engine’s online exhibition “Ocean,” which launched in January 2019, showcases works by 103 artists in a virtual body of water. The videos, digital sculptures, and photographs float just above the surface, and users navigate among them via keyboard control. Slime Engine is represented by Shanghai-based MadeIn Gallery, a partnership that has explored forms of cooperation that differ from conventional artist-gallery relationships. In June 2020, the collective worked with MadeIn to mount a version of “Ocean” at Theatre X, an art mall in Shanghai, where one viewer at a time could enter a small amphitheater with tiered seating and explore the exhibition on a large-scale TV screen via DualShock controller.

Like New York’s Showfields and Beirut’s Aishti, Theatre X is one of many malls around the world that incorporate art in the retail experience, usually by placing works near escalators and entrances, or in designated exhibition spaces. Adrien Cheng, a Hong Kong billionaire and property developer, is arguably the most successful proponent of the art mall. He has opened five such retail centers in mainland China over the last decade, following one in Hong Kong in 2009, supported by the extensive collection of his K11 Art Foundation.

Slime Engine’s new group show “OVO Mixing” is on view at Shanghai’s chi K11 through February 15 as part of another group show, “Mirage or Reality.” Sprawling throughout the art mall’s basement museum space, “Mirage or Reality” features the work of fifteen other contemporary Chinese multimedia artists. “OVO Mixing” is scattered among them in the form of fifteen portals, each embedded in a makeshift aircraft galley, with screens and niches for displaying artworks where service trolleys and food storage should be. Roughly the size of a small air streamer, each semi-enclosed space presents a version of one of Slime Engine’s online shows. Together, the fifteen iterations emulate the multiplicity and simultaneity of digital space in a concentrated physical format and amplify the status of “OVO Mixing” as an exhibition within an exhibition.

Exhibiting in malls has become more the rule than the exception in China, but Slime Engine’s repeated engagement with these sites is more than a capitulation to a domestic trend. Shopping malls are perhaps one of the most international, stateless spaces in the “developed” world. Like casinos, they often lack windows. Many of the stores sport brand names of multinational companies. Currency is spent with plastic, not the paper bills that carry some cultural markers. One could argue that placelessness is a hallmark of the most popular retailers of all: Amazon, AliExpress, and the commercial colonizer of airspace, the institution formerly known as Skymall. Airports themselves have come to function as exclusive shopping malls, where international travelers pass through customs into the duty-free zone, surrounded by perfume, jewelry, liquor, and other appealing commodities. In China, malls are associated with a growing middle class; shopping there is a way to signal social affiliation. But the expansive online practice of Slime Engine means that any reading of “OVO Mixing” should not be restricted to that context.

Often derived from amalgamations of real places, Slime Engine’s projects distort, transform and reconfigure familiar worlds in unfamiliar ways.

Often derived from amalgamations of real places, Slime Engine’s projects distort, transform and reconfigure familiar worlds in unfamiliar ways. One of the portals displays “territory” (2020), an online exhibition where a click on one of five fragmentary maps leads the viewer to a platform with a 360-degree vista of composite cities. The Petronas Twin Towers of Kuala Lumpur, New York’s Empire State Building, and the Shanghai World Financial Center might share the same remixed skyline. Empty streets spread out below, billboards advertise imaginary lifestyle products up above, and comments from other users swim in the air. While some of the virtual artworks in “territory” jump out at you—there’s a huge creature with flamelike hands and a stamen extending from between its eyes—other works seamlessly blend into the environment, new and old media formats embedded in the disorienting cityscape. This portal is prime example of “OVO Mixing” and its thematic connections transporting the audience via maps and other representations of sites both real and imagined. Filled with surreal imagery and juxtaposing disparate styles of the various artists invited to take part, the portals have a dream-like quality, an organization of potential possibility in a realm of plausible deniability.

The portal displaying the aforementioned “Ocean” lights the watery blue backdrop with an artificial sun that rises and sets on its own time. Works with more reflective surfaces seem to glow in the night, in conversation with the virtual water’s undulating surface. Another station displays Slime Engine’s Headlines (2020). Comprising fictionalized op-eds from other planets, the piece highlights a narrative about the “novel hook virus” that emphasizes its negative effect on the economy. When the work came out it felt like a near-future dystopia. Today, with the growing concern that economic rejuvenation is being prioritized over individual and collective health, Headlines feels bleakly prescient. It seethes with an unease that can only come from a certain amount of distance—perhaps a few thousand feet above sea level.

Showing Slime Engine’s various exhibitions side by side in a common apparatus reinforces their reality outside of any individual, single-screen engagement with them, and further materializes the real-time aspects of the collective’s cumulative, constructive practice. Their shows exist with their own articulations of solar time and gravity, in a range of social contexts and vacuums. They are not programs to be run, but experiences to be had—inviting audiences to play in a world, straddling hemispheres and timelines, and not with a game. In Art and Telematics: Towards a Network Consciousness, (1983) British artist Roy Ascott wrote that “networking puts you, in a sense, out of body, linking your mind to a kind of timeless sea.” “OVO Mixing”, in its attempts to connect and unify Slime Engine’s practice, builds a network of exhibitions and artists by giving it a body, a vehicle in the form of an airplane galley, that exists in a seemingly timeless, stateless place. They ask us to consider our bodies in relation to our screens and the world by echoing and articulating an increasingly fractured sense of being. In a world marked by distorted experiences of time, where distance is collapsed and borders fluctuate between membranes and iron curtains, their work posits unsettling truths and alternative futures to help us question, and sit with, the present—a creative gesture perhaps best suited to being made on a long-haul flight, or in a shopping mall.

Sarah Forman is a digital content producer at White Cube in London.