Jack Kaido

A digital painter encourages the development of his chosen medium by collecting and advocating for the work of other artists.

Thefunnyguys—an anonymous collective of three Belgian brothers—has what one member describes as one of the most “horizontal”collections of generative art in the NFT space. Ranging across platforms, blockchains, and edition sizes, thefunnyguys’s collection has grown from a well-researched investment portfolio into a testament to their passion for the generative art community on both Ethereum and Tezos. In the following text, one member of thefunnyguys—who also serves as an advisor on generative art for the NFT investment firm Metaversal—explains how the group’s early interest and success in trading digital sports collectibles on NBA Top Shot opened the door to an entirely new world of art appreciation in the form of NFTs.

I started thefunnyguys with my two brothers in December 2020, when we began collecting on NBA Top Shot. It was then that the idea of digital ownership immediately clicked—that experience turned the blockchain into a concrete concept I could really believe in. Even though I’m not a huge basketball fan, Top Shot was one of the best consumer experiences I’ve had in the NFT world to date, because it’s affordable and you don’t have to worry about gas fees, MetaMask wallets, or seed phases; it’s a very web 2.0 experience, which made it the ultimate gateway drug for learning about NFTs. Since we got into Top Shot early we were able to collect some of the very rare pieces, called Cosmics, at a low price. After the platform took off in early 2021, we were able to turn a small investment into an extremely valuable collection. We used proceeds from Top Shot sales to kickstart our digital art collection.

I personally don’t have a background in art—I studied business engineering, and I haven’t collected any physical work before. Our grandfather was an avid art collector, and our mother has always been passionate about art, taking us to galleries and museums, so there was some interest, and NFTs have kindled the fire. In January 2021, I discovered Art Blocks and was able to get in on the early iconic drops like Dmitiri Cherniak’s Ringers (2021) and Kjetil Golid’s Archetypes (2021). Since then, generative art has been my main focus. The concept of being able to mint a unique piece of art on the blockchain was mind blowing to me, and I see generative art as a way to extend human creativity. By using computer code, these artists are able to delineate boundaries for an output, and within this output space discover possibilities that can even surprise the artists themselves.

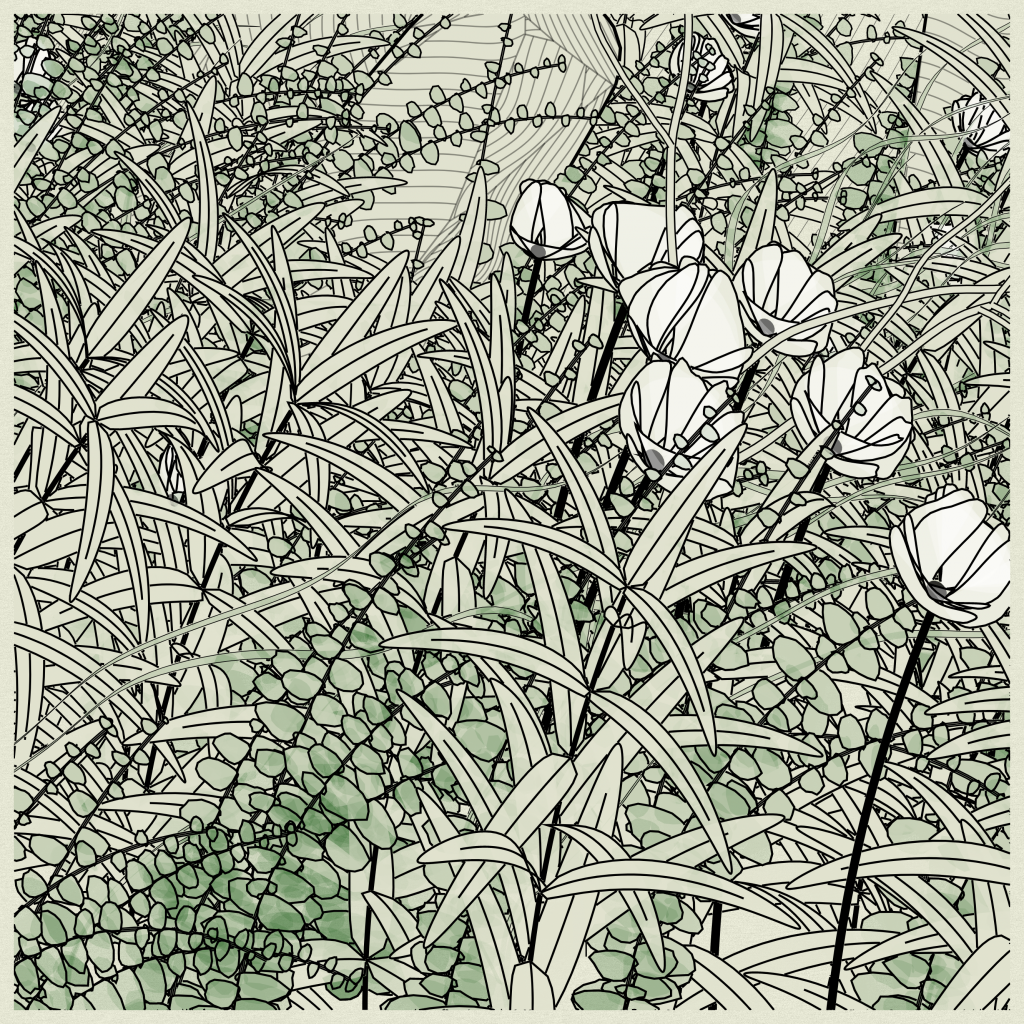

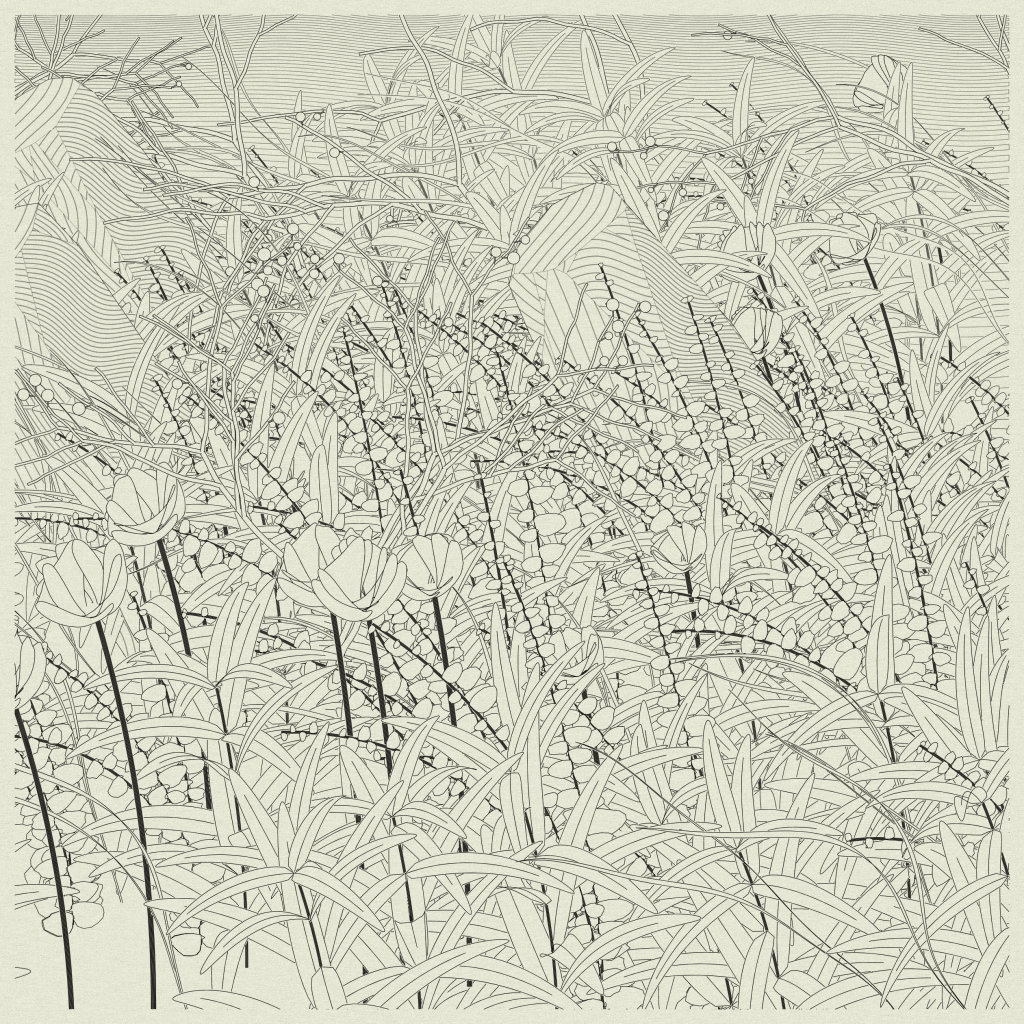

An artist whose work I really appreciate is Zancan. We own multiple pieces from his Garden, Monoliths (2021–) series on fxhash, which I think is one of the best generative collections currently in existence. Artists like Zancan use generative art to bring the unique qualities of nature to the digital world. Another nature-inspired artist is Anna Ridler, whose work Truth to Nature Flower II (2022) is in our collection. AI artists like Ridler inspire me to look at nature in a different way, as they use technology to create organic forms that do not exist in the physical world.

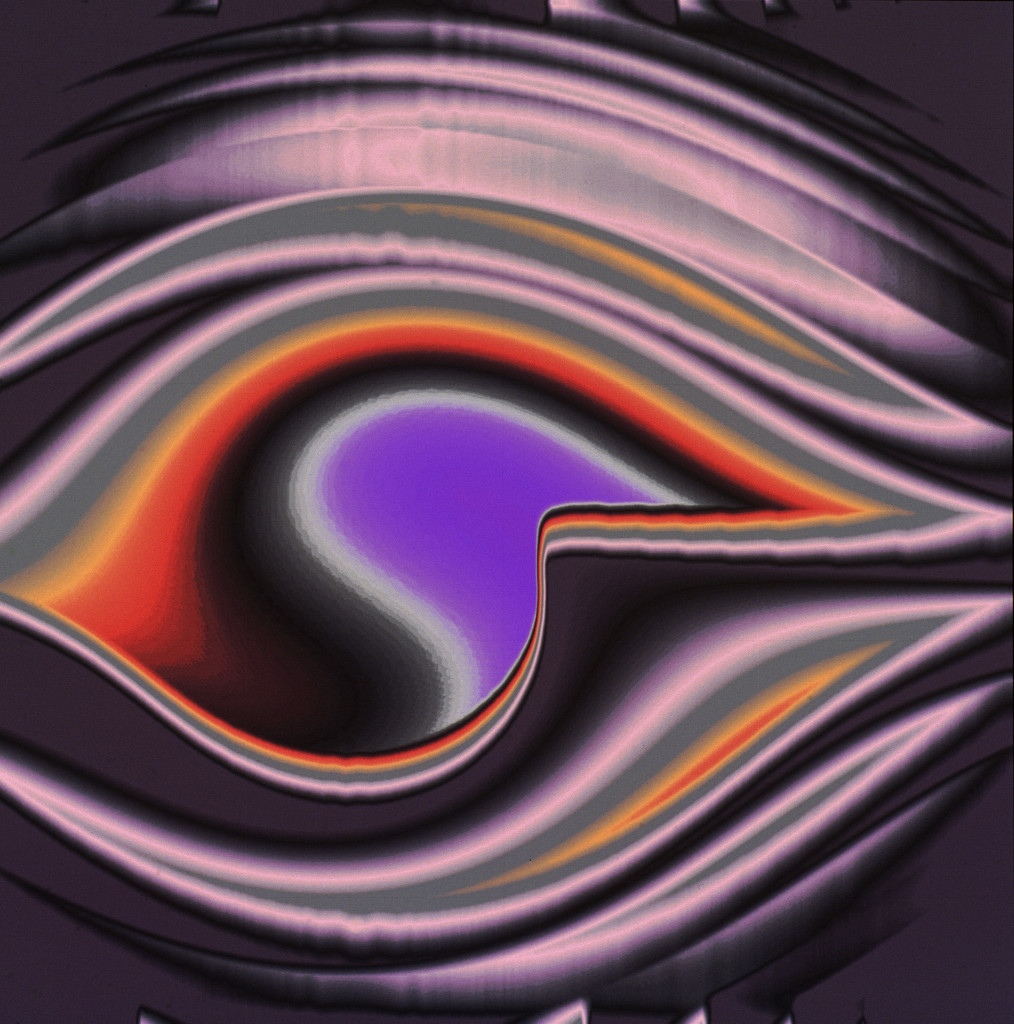

Anticyclones (2022) by William Mapan is another series I’m excited about. Mapan is one of the bridge builders between the analog and digital worlds. He has another series on Tezos, called Dragons (2021), which also has a handcrafted, cut-paper quality. It’s impressive how he’s been able to recreate the act of drawing by hand in such a realistic way. Mapan is a student of art history, and has been obsessing over color—resulting in over twenty unique palettes in Anticyclones. He truly brings a unique aesthetic to the generative world.

Due to my early experience with the NFT market and my background in economics, I also act as an investment advisor for Metaversal. They’re not only an NFT investment firm, but also have their own creative studio where they work with existing and new intellectual property and find ways to bring it into the metaverse. I was their first investment analyst, and helped set up the investment framework, building a thesis on every single niche within the NFT ecosystem. I now advise them on potential NFT investments and provide guidance to the new investment analysts.

Although I’ve collected a lot of amazing 1/1s on Foundation and SuperRare, like Zach Lieberman’s grid on grid study (2022) and Manoloide’s bababa (2019), I now primarily collect on Tezos. I think when it comes to art, the strongest community exists there because of the low transaction fees and lower barriers to entry. Tezos makes it easier for artists to experiment and release work, and to get access to generative art platforms like fxhash without having to go through a curation committee. Highlights from my Tezos collection include Behind curtains: the sea (2022) by Iskra Velitchkova and MOLDORM (2022) by Nicolas Sassoon.

I think a lot of collectors in the NFT market consider projects like Snowfro’s Chromie Squiggles (2020) or Larva Labs’ Autoglyphs (2019) to be the original collections of generative art, and not simply the first to use the blockchain as a medium. They may not realize there is a long history of artists making generative computer art, which is why I’m so glad that early pioneers like Herbert W. Franke are starting to be recognized in the space, and are then themselves able to enter in a thoughtful way. I have a work from Franke’s “Math Art” series (1980–95), which was recently minted as an NFT, and was made using computers at the German Aerospace Center. Franke was trying to use the computer and algorithms to figure out why people enjoy certain things aesthetically, and what beauty truly is. He found a link between mathematical formulas and beautiful pictures, and I think that’s very clear in this collection. In the early days of generative art, even before this collection, computers used to fill entire rooms, and lacked interfaces. Artists like Vera Molnar had to work with punch cards and wait for prints to be plotted to see the results. It’s really incredible that she managed to create exceptional art with the technology that was available.

I think that’s what’s most interesting to me about being an active member in the generative art space: not only being able to discover new artists and support their practices, but in the process also learning about the history of the medium. Computer art has a long, rich history, and it’s important to me as a collector to continue to learn, while embracing those practices and communities that are furthering the medium today.

—As told to Lauren Studebaker