Centre Pompidou

Curators Marcella Lista and Philippe Bettinelli discuss the museum’s landmark acquisition of NFTs.

Inspired by the celebration of industrial progress that was the Great Exhibition of 1851, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London was founded with a mission to educate the British public—manufacturers, designers, and consumers—in the best of art and “applied science.” The institution has always placed technology at the forefront of its acquisitions program, from its well-known collection of plaster casts of historic statues to its significant holdings of computer-generated and digital art. Below, the V&A’s digital art curator Pita Arreola discusses the gradual formation of this collection, beginning with a set of plotter drawings made to mark a landmark cybernetic art exhibition in 1969, and extending to recent works exploring AI and neural networks. She explains the unique challenges and opportunities that arise when stewarding these works, and the importance of ensuring that their histories are properly preserved and presented.

The digital art collection at the V&A is part of the museum’s art, architecture, photography and design department. There are five of us in a curatorial team led by Corinna Gardner working with the digital art and design collections. My colleague, Natalie Kane, takes care of the digital design collection, which includes things like video games and apps. I’m curator of digital art—although sometimes the frontiers of these categories get pretty blurry.

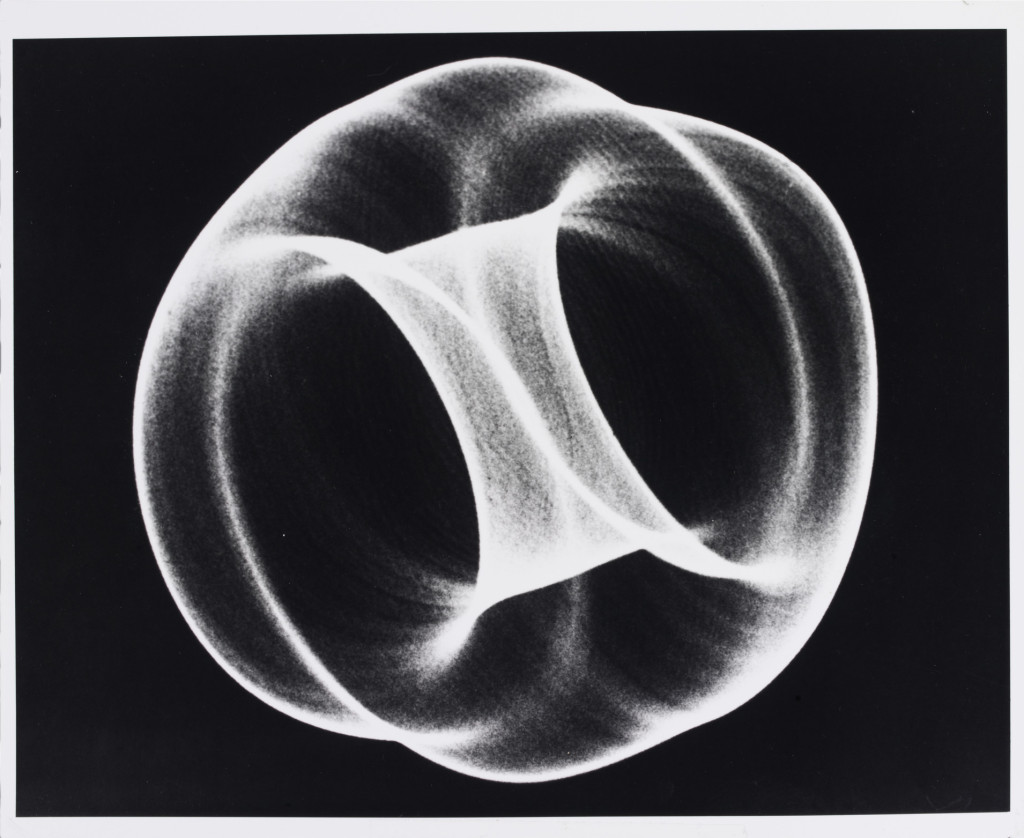

The collection items span from the 1950s to the present. Most of the early pieces are works on paper because computers were massive back then, and artists were dependent on printing and photographic processes to actually make the works. The earliest item in the collection is a photograph from 1952 by Ben Laposky, showing electronic beams on an oscilloscope. Then we have many computer-generated drawings printed with plotters from the 1960s and ’70s, and works from artists experimenting with virtual reality, and finally born-digital objects from the 1990s onwards.

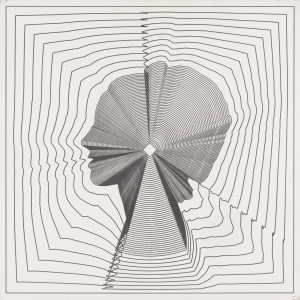

The V&A’s first acquisition in this field was in 1969, the year after “Cybernetic Serendipity,” a landmark exhibition of cybernetic art curated by Jasia Reichardt at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. There was so much excitement around that show: people queued outside to get in. To mark the occasion, the ICA and Motif Editions put out a portfolio of lithographic prints based on plotter drawings by different artists and groups: the Computer Technique Group, Charles Csuri, James Shaffer, William Fetter, Maughan S. Mason, Donald K. Robbins, and Kerry Strand. The V&A acquired the whole set for 5 GBP and the works entered the museum’s circulation department, which until its closure in 1977 was responsible for traveling exhibitions of material held in the V&A.

Despite the wave of interest in computer-generated work, it was not particularly well-recognized as an artistic endeavor in the late 1960s. But the V&A has always been interested in the overlap between art and science—the institution’s original name, when it opened at its first site in 1852, was the Museum of Manufactures. So there has always been this interest in processes and materials, as a way to illustrate social change, as well as showcasing the best of art and design.

Still, for the next few decades, the collection grew at a relatively slow pace. The turning point was in the mid-2000s, when the museum acquired two significant collections and archives of digital art: the Computer Arts Society and the Patric Prince archives and collections, each consisting of around two hundred original artworks, plus other material such as correspondence and ephemera. The Computer Arts Society was founded by a group of artists in London in 1968, but it soon grew into an international community, organizing exhibitions and other events with digital practitioners from across Latin America, the United States, and Asia. Patric Prince was an American art historian and a big promoter of computational art for many decades.

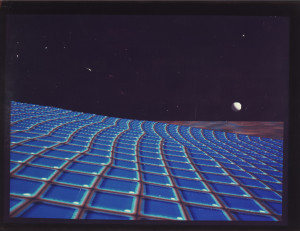

While born-digital objects are very important for the collection, we are also doing a lot of work right now to revisit this earlier period and to document the context in which works were presented and produced. For example, we have a work by David Em called Approach (1979), created when he was artist-in-residence at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. What we have is a photograph of the 3D virtual environment that Em created to visualize Voyager 1’s Jupiter Approach. With this kind of work, there can be issues around copyright. Most of the time the artists were working with laboratories, whether at NASA, MIT, or Bell Labs. But there is also a conceptual challenge: what exactly is the work, and what’s documentation? Would David Em see his virtual reality environment, which was primarily created for space explorers, as the final artwork, or the photographic print? Of course, the artist himself is best placed to answer this.

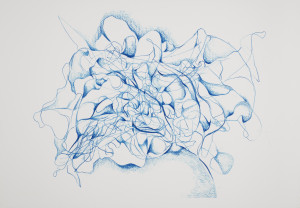

The same questions come up when collecting contemporary digital art. You see it a lot in the NFT scene, with some people selling live code and others selling screenshots of the running code. At the V&A, the most recent acquisition we’ve finalized is a work entitled MEMORY (Drawing Operations Unit Generation 2), 2017–22, by Sougwen Chung, a Chinese-Canadian artist, researcher, and coder. Over the years she has programmed and built a series of AI-driven robots, using recurrent neural networks to “teach” the robots to mimic her own hand-drawn gestures. For Chung, the core of the artwork is the performance of the robot itself. We couldn’t collect the robotic arm used in MEMORY, because it’s still part of her artistic practice, so we had to think about how to acquire the piece in a way that would be meaningful for audiences now and into the future. As a museum, we want to collect works so that people can interact with all aspects of the software and the experience. That’s where hybrid collecting comes in. For MEMORY, we collected a print of a drawing made as part of a performance, a video where the artist explains how she created the work, a model of the neural network, and also a 3D-printed sculpture made using the same neural network.

We want to “future-proof” any work that we acquire—both practically and conceptually. That’s a key question around the blockchain: how do you acquire a work made using a technology that’s so difficult to preserve? We’ve been speaking to artists and making this conversation part of our public program as well. We feel it’s important to properly research this technology, because of the potential social and environmental impact it could have outside of the art world.

NFTs have captured a moment, but digital art and digital creative practice are so much more; they have a breadth and criticality that is so vital to investigate and showcase. I also think it’s important to look back and think about past moments in digital art history. With digital-based projects that emerged during the pandemic and the rise of NFTs in public discourse, it’s common to hear people say that until now museums have never engaged with digital art practices. This erases major events such as the ICA’s show in 1968. That same year, “The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age” was staged at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. And at the time there were movements like New Tendencies in Zagreb and Experiments in Art and Technology in New York, both of which had institutional recognition. We need to preserve these histories, so we can properly recognize the work of the people who laid the foundations for this field. And so that we can give context to the here and now.

—As told to Gabrielle Schwarz.