The Digital Combine

The metadata field of an NFT’s smart contract offers a new way for artists to suture elements of hybrid works.

In the halcyon days of 2021, NFTs were heralded by proponents for their potential to transform the livelihoods of artists working with digital media. Detractors questioned whether “serious” artists would (or should) get involved. Since then, the hype and the commotion have simmered down—and the market has stalled, too. But plenty of artists, from crypto natives to blue-chip names, have continued to explore the creative potential of NFTs and blockchain technology. How, and why, have attitudes to NFTs changed—and what is it like to make work in this constantly evolving environment? Outland invited a group of artists to consider the shifting perceptions among their peers and communities, and how their own studio practices have developed since the advent of NFTs. For more reflections on 2022, see our survey of art professionals.

This year I had my first solo show at Gazelli Art House in London, “Moments Spent with Others.” We released the works as an NFT collection. I showed a work called Infinite Glimpses atVerticalCryptoArt’s “Proof of People” festival in London. I also created a series called 16-Bit Machine Machines, and produced a tribute to the late computer art pioneer Herbert W. Franke, entitled You, Me and the Machine. Despite these projects, I don’t consider myself someone who makes NFTs. I would be making these things—and indeed I already was—before NFTs. NFTs can do many things, but at their most basic level they are a distribution mechanism. I’m here to make art and disseminate that in a way which is suitable for the medium. Most of the time, before NFTs, digital art it had to be transmuted into an analog form before it could be sold. NFTs allow for digital art to be sold, acquired, and owned in its raw unaltered state, without transmutation. They also allow for a deeper relationship with collectors. Now I can bring things to market, either with my own smart contract, free of platform restrictions, or through the gallery which represents me.

A positive change I have seen over the past year is less talk about over-hyped PFP projects and more talk about art. But a lot of narratives are still focused on the prices and not the works themselves. So there’s more work to be done. Ultimately, I’d like to see the term NFT disappear from our lexicon, and have it replaced with art.

On the occasion of my solo exhibition, “The Garden of Emoji Delights,” at Fotografiska Tallinn, I made an NFT to raise money for Ukraine. My work was included in exhibitions and festivals including “CryptoPong,” curated by Radar Contemporary at Nikolaj Kunstalle in Denmark; Refraction Festival; “Artists Who Code” with Artsy and Vellum LA; “Unsigned” by Anika Meier and Operator; “The World is Not Enough,” curated by Manuel Rossner in dialogue with Anika Meier; “Digital Baroque: History Meets Algorithm,” on 4Art Marketplace; and Wagmi Wine’s interactive NFT wine gallery.

I did not have trouble imagining the undertaking of any of these projects, because I’ve been making digital art for a bit of time. I see NFTs as an extension of what I’ve been doing, although I’d never had my signature counted as a work of art before. That said, everything has been changed by NFTs—just as everything changed too in the mid-1990s and early 2000s. At that time, I threw away all my paintings and began to embark on a practice as a digital artist. Over the past two years, my day-to-day studio practice has evolved, for the better (and worse at times), through increased dialogues about digital art and its distribution, and the acceleration in the production and selling of art. This year, I found I had to step back, and I began posting TikTok videos as “unminted” sketches, because I felt that I was minting pieces prematurely to keep pace with the market. I’ve run quite a few physical marathons, but I suck at running sprints. I discovered that I needed to slow down. Still, some NFTs are like Picasso paying his bill at a cafe with a quick sketch. That’s undoubtedly a good thing if more artists can finally pay their bills.

In the wider digital art community it seems that more and more people have come around to accepting NFTs as part of our ecosystem, even if they still may not want to participate. There is less vitriol, if some indignant resignation, but I think a larger percentage of artists with technology-based practices understand that blockchain is here to stay despite the vicissitudes of the market. Hasn’t the term “post-NFT” been floating around? I also teach. It was fascinating, through a lecture series I ran this semester, to find how polarizing the topic still is for students.

The biggest (and much appreciated) surprise of the past year is the continued supportive nature of many NFT art communities, and the generosity of their members. At a point when there’s no longer as much money to be made, people still believing in the “art” aspect of all of this is heartening.

I would say that everything I’ve worked on this year would have been doable a year ago. Because I am now rich, I have unlimited time to work on my art. I can ignore most emails and meetings, except for emails from Outland asking me to do surveys, because I actually like Outland.

How have things changed in the past twelve months? Well, the TradArtWorlders have given up their anti-NFT crusades and are now wholly committed to a) trying to get dat cash; b) saving the souls of these poor NFT philistines by spreading the word of The One True Canon; c) positioning themselves as ThoughtLeaders in the TradArt space by loudly signaling that they are the brave Columbuses who, uniquely, can guide institutions and collectors to the New World. The NFT is just becoming the de-facto commodity form for digital art. This comes as no surprise to me!

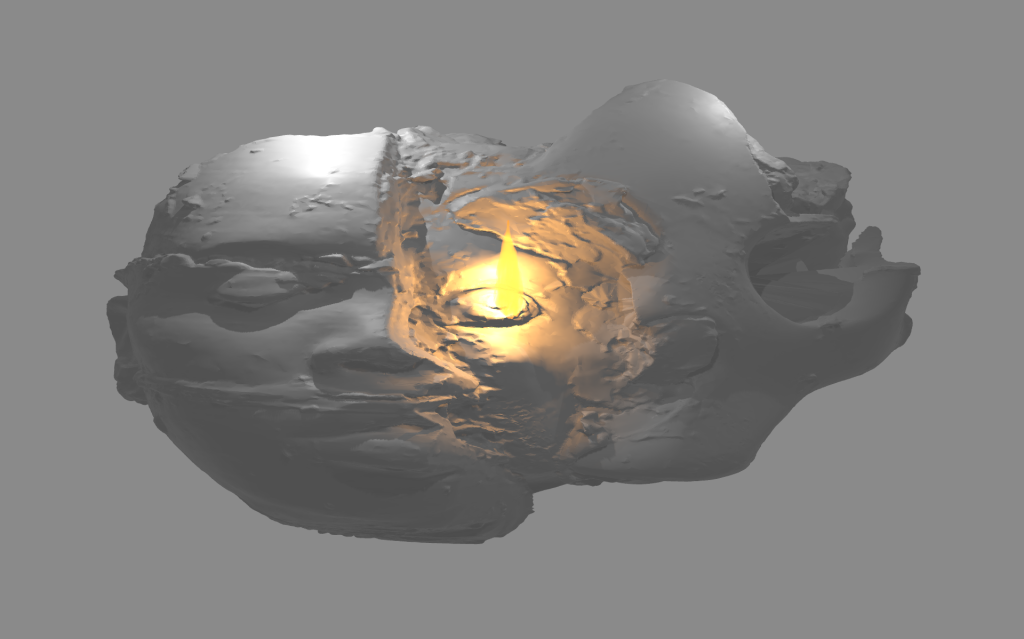

I’ve had three blockchain projects this year. With Art Blocks and Pace Verso, on Ethereum, there was Petro National. On the Tezos platform fxhash, I released Bone Work (Gulf of Mexico). Finally, I produced an “artist sketch,” Smoke Hands (Dark), for a show curated by Jesse Damiani on Feral File—that was also a Tezos project. The emergence of these different platforms has introduced a hugely valuable range of languages and approaches, which was missing in 2021 with places like Foundation and SuperRare. It felt more organic for me to work with them.

All three projects hinge on the WebGL API, to allow my historic medium of game engines to be rendered in the browser and to be available to collect using the blockchain mechanism. My first NFT was much earlier—all the way back in March 2021 when I released Western Flag (NFT) on Foundation. I was riled that everyone was speaking about Beeple’s Everydays as digital art and made my work to stake a little ground for digital artists who’d been making pertinent digital work for decades. The work was a 30-second video excerpt from an artist’s proof of an earlier simulation. It is in effect the first (and last) video or mp4 I will ever make and, truthfully, it was brutally hard to leave the vast spatial and temporal planes of the game engine to make a linear video, no matter how beautifully it loops. Finding WebGL has allowed me to engage the radical exhibition and distribution space that the blockchain offers—but to keep in touch with my artistic self.

I tend not to use the word NFT, and in my opinion we have to separate the freak-out about overpriced jpegs and mp4s which happened post-Beeple from where we are now. Generative art came up fast and is among the most interesting categories in the web3 space. Contemporary artists are using contemporary languages to scrutinize contemporary conditions. Alongside that, it’s wonderful to be speaking now to far more people about digital art online. I’ve reconnected with old acquaintances, such as Casey Reas, and found a much bigger community—whether through Twitter or curators such as Anika Meier—than I could have ever reached when showing my work in galleries and fairs and biennials. I am thrilled that the specific focus on place and geography can be resisted a little. I am so open to witnessing the work of digital artists in the browser: collecting them via the browser and showing them via the browser.

In November I had a solo show, “Gray Matter,” on Feral File. I also had a piece, Slave Ship Diagram, in the “AIAD Artificial Intelligence—Analog to Digital” collection on Tezos. I was working on the Feral File project for a long time, so I could imagine doing something similar this time last year. Maybe the AI project would have been more challenging then. But more and more, since NFTs arrived, I can do what I want. I can talk about digital and physical sculpture interchangeably without having to explain as much. And it is no longer weird to art people that I want money for my digital work, too.

Although there’s still plenty of discussion around NFTs, everyone seems to think the whole thing is over now. I think it’s just mutating. The big money is gone (at least on the surface) but the love of digital art continues. May it be ever thus.

This year I released Fragments, my first PFP collection, with Outland. I could have launched a PFP collection earlier, but it took some time before I was comfortable with the thought of releasing so many pieces (7,000 NFTs) and managing a community base. In terms of how NFTs have affected my day-to-day activities, I now follow a lot of YouTube channels and podcasts that discuss the latest news about NFTs, so I can stay up to date.

In my circle, most talk about NFTs has cooled off. I know one very talented artist who became bitterly disappointed and depressed after their collaboration with a major celebrity faltered. The death of royalties is also pretty unfortunate. Artists viewed this as a major innovation—hearing about perpetual royalties from other successful projects was a major impetus for me to start my own PFP project—but it seems the dream is over. However, another friend of mine is doing well with selling one-of-ones and has grown his following to thousands of followers from essentially zero, so he is extremely happy and encouraged by the community that has grown around his new work.

In the past year I’ve created many one-of-one NFT pieces and two large collections. The collections are serials—unique pieces that are part of a family, created generatively (in my case with AI), but also worked on by hand. The first serials collection was AI Spaceships, featuring 501 spaceships that are part of a narrative of the future potential of climate change. The second serials collection, Rabbit Takeover, features a wide variety of rabbits cavorting about in a post-armageddon world.

A quick look at any chart of NFT art sales will show how dramatically collecting has fallen off over the past year. The plunge in cryptocurrency values, constant bad news about exchanges, and anxiety-producing scam news in one’s Twitter feed do often make me wonder about the long-term viability of the space. I am hopeful that we will pull out of the current slump and that some amount of regulation or software tools will come into play that make the space less volatile and safer for the average artist and collector.

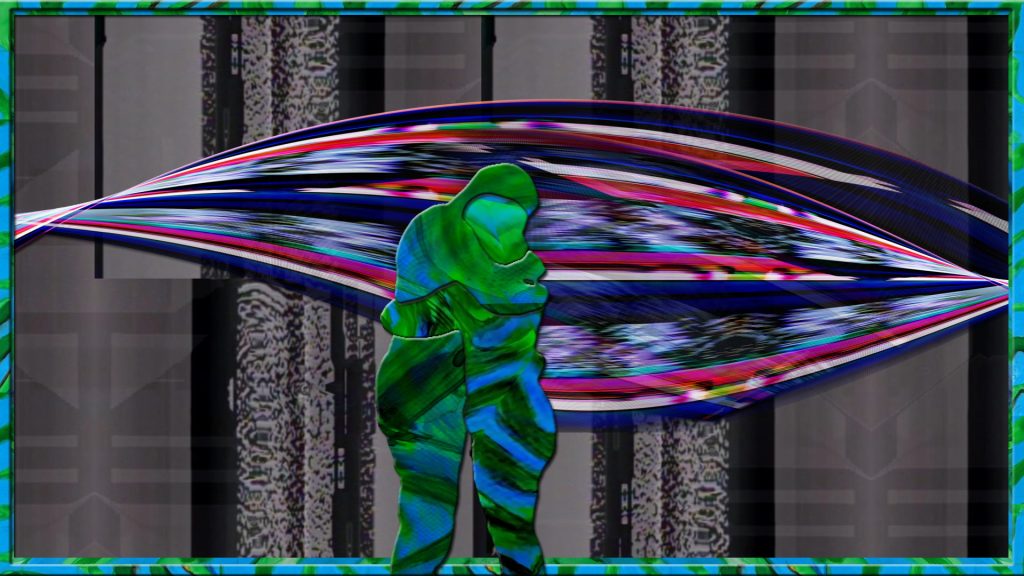

This year we continued our series of Hugs on Tape animations, which we started in 2021 and draws on work that predates the NFT boom. We took part as curators in the Lonely Rocks “Curator House” exhibition at Untitled Art Fair in Miami. We also created our first on-chain generative artwork, Tide Predictor. We’ve always worked in multiple media—physical objects, single-channel videos, music, performance—and the support we’ve received from the digital art and NFT community has allowed us the necessary time to focus on new work. In 2021, we’d imagined translating our analog video work into NFTs, but would not have thought of the method of translation, capturing the simplicity of our RGB video generation with code-derived imagery, that we used in Tide Predictor. We also didn’t anticipate that we would be working with Art Blocks and joining that community.

In 2021, NFTs were viewed with more resistance and suspiciousness by the traditional art world; it’s incredible to see how things are developing. While the general public conversation has been more about the crypto winter—and for those outside the “art NFT” world, the term “NFT” is still generally perceived as denoting PFPs and memes—it has been been interesting to see more traditional art collectors become interested in learning about and acquiring digital art. It seems like we are now in a more mature environment. Separating out some of the hype and speculation allows audiences to engage deeply with the art and underlying ideas, while viewing and collecting the NFTs. This pushes innovation, such as new minting experiences and gatherings for in-person events as we come further out of the pandemic, and new creative processes based on web3 concepts and technologies. We aren’t surprised by this growth, but are excited to push the boundaries further in 2023.

This project was instigated by Sarah Zucker, artist and Outland’s first guest editor, and compiled by Outland deputy editor Gabrielle Schwarz.