ICA Miami

Director Alex Gartenfeld talks about the acquisitions of a CryptoPunk and an NFT by Nina Chanel Abney, and how they fit in the collection.

What does it mean to collect art made with computers? The NFT market has popularized the ownership of digital art, but museums have spent decades studying the issues involved with collecting reproducible and variable artworks. How important is display hardware to the meaning of an artwork? What about the tools used to create it? What happens to an artwork when the software and hardware originally used to show it become obsolete? What kind of story does a collection tell, and how does it build connections between individual works and broader histories of art and technology? In the interview below, Tina Rivers Ryan discusses these questions in relation to the collection of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, where she is an assistant curator.

The Albright-Knox Art Gallery was founded in 1862. At that point there weren’t that many art museums in America—we’re actually the sixth, predating the founding of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York by about ten years. Unlike the Met, we are not an encyclopedic institution. We are a museum devoted to modern and contemporary art from the nineteenth century onwards. We’ve supported artists working with emerging technologies since at least 1910, when we became one of the first American museums to host an exhibition of photography as a fine art, guest curated by Alfred Stieglitz.

In the 1970s Buffalo became the epicenter of a new field called media art. The very first academic program devoted to it was formed at the University at Buffalo. Its faculty members included avantgarde filmmakers and early video artists like Tony Conrad, Peter Weibel, the Vasulkas, Hollis Frampton, and Paul Sharits. We actually hosted some of their early major presentations, not in our auditorium but in our painting and sculpture galleries: film and video in the architectural and discursive space of fine art. We collected our first piece of video art in the 1990s. It’s a major work by Nam June Paik called Piano Piece (1993). Now we acquire not only video, but also sound art, software art, kinetic light art. We’re also putting together survey exhibitions to help define this field.

When we make an acquisition, we are looking for works that both pioneer a new path forward and speak to the history of art and the history of our collection. In the spring of 1965, we presented an early American survey of kinetic and op art. We bought most of the works in that show, and now we can see them as an important link between our holdings of postwar abstract art and later generations of artists using technology. We’re still building on that legacy.

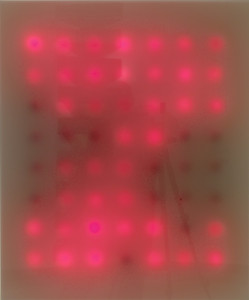

For example, it made a lot of sense for us to acquire Leo Villareal’s Red Life (1999). It contains a grid of incandescent bulbs behind a Plexiglas screen that softens the lights of the bulbs going off in random patterns, inspired by the rules of John Conway’s famous Game of Life. Visually this work is very much in dialogue with the geometric abstraction from the 1960s, in part because of its use of the monochrome grid.

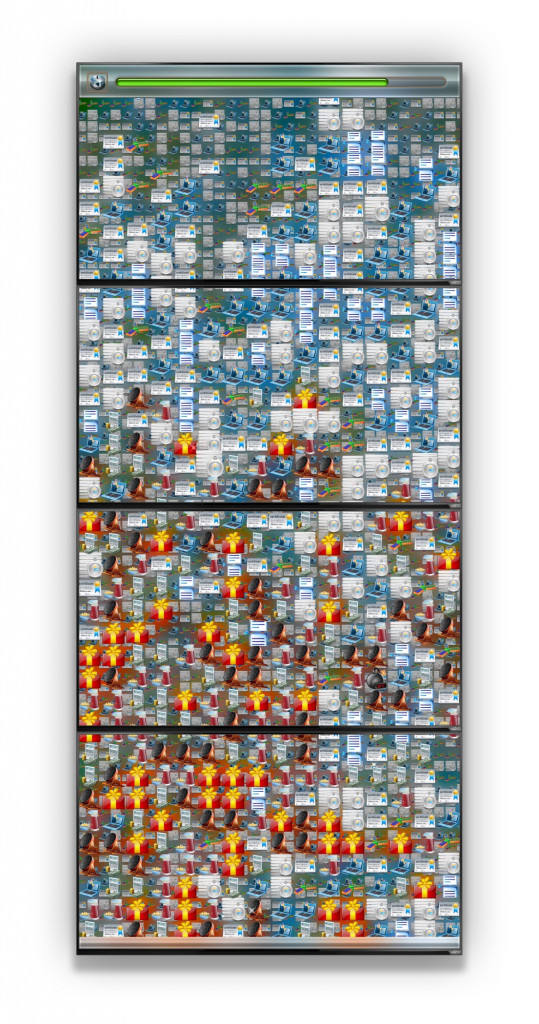

Tabor Robak’s Free-to-Play lite (2014) was shown in our 2015 exhibition “Screen Play: Life in an Animated World.” It’s a simulation of match-three games, where you have to line up a sequence of images so they delete and drop out. Robak made it using custom software and generic icons that he bought off the internet. On the one hand, this work is very much about contemporary digital games and the way that our attention spans are being captured by these algorithmic processes. But on another level, you could place Free-to-Play lite in the tradition of geometric abstraction. It’s shown on four flatscreen panels mounted one on top of the other, forming another kind of grid. As you watch the game play itself, grids of icons come into and out of alignment. So it’s really in dialogue with those formal legacies, even though the icons themselves may not be abstract.

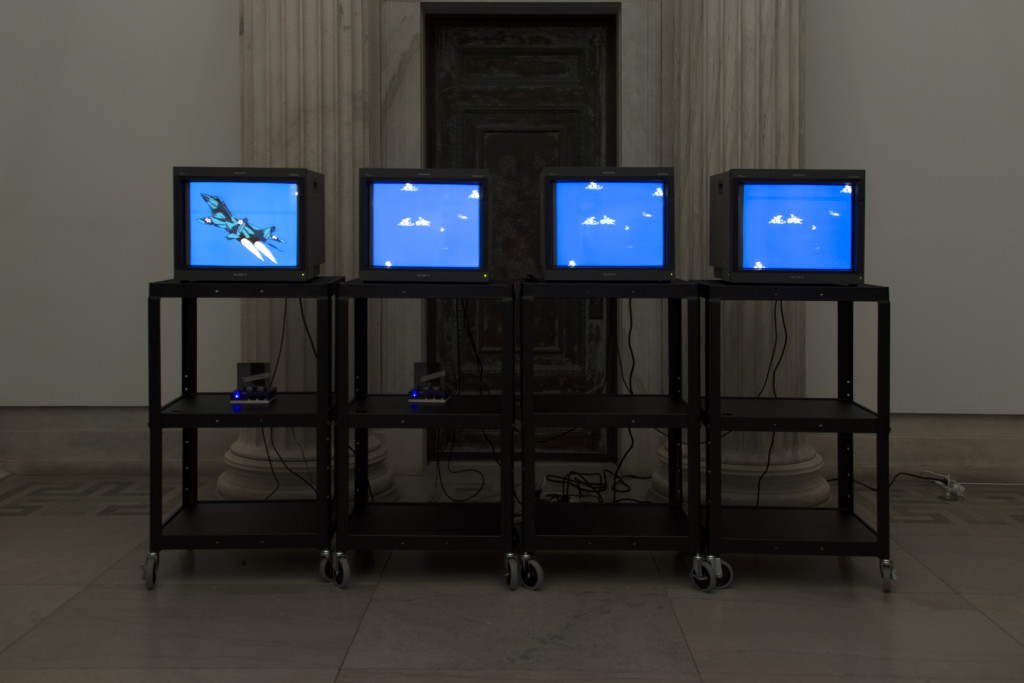

Another important example of an artist using games in our collection is Cory Arcangel, who happens to be from Buffalo. To make his MIG 29 Soviet Fighter Plane and Clouds (2005), he hacked two cartridges from Nintendo’s MIG 29: Soviet Fighter game, released in 1989. He essentially cut and pasted the graphics so the jet just continuously flies through these scrolling clouds. By reducing the game to a kind of minimalist landscape painting, the work calls into question the values of these games that are about achieving an objective through simulated violence.

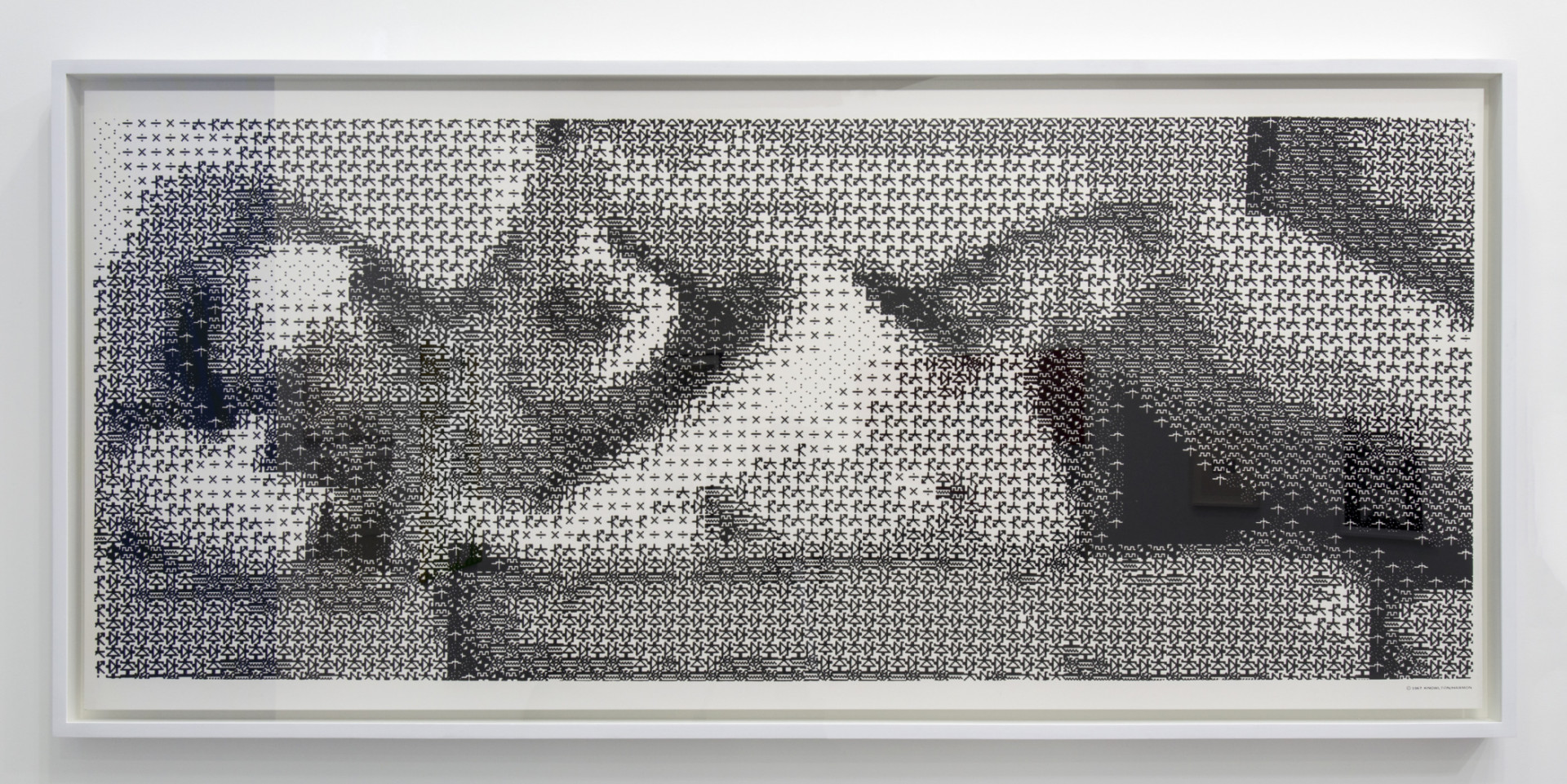

We were very fortunate a few years ago to acquire an edition of the iconic Computer Nude (Studies in Perception I), 1967, which was made by Leon Harmon and Ken Knowlton at AT&T’s Bell Labs. They digitally scanned a photograph of dancer Deborah Hay and turned it into a bitmap mosaic, like ASCII art. It became famous partly because Robert Rauschenberg had a copy of it in his studio during a press conference for an event for Experiments in Art and Technology, a program that paired artists and engineers to create media projects in the 1960s. Documentation from that press conference was in the New York Times, and Computer Nude ended up being the first full-frontal nude in the Times. This work is about the history of photography, because it’s connected to early programs for processing photographs digitally. It’s also about the history of the nude and the history of figuration.

We’re trying to build on that acquisition and add more to our collection from that early moment in the history of digital art. Recently we acquired an amazing print by Ruth Leavitt Fallon. She was trained as a painter and was married to a professor here in Buffalo. I originally knew her as the editor of Artist and Computer (1976), an important collection of interviews with the first generation of computer artists, people like Vera Molnar and Manfred Mohr. She collaborated with her husband, who worked with computers, to write a program that allowed her to deform images. She was inspired by these rubber dollar bills that she had as a kid that could be twisted and warped. We now have a beautiful work by her, Inner City Variation II (1975), with nested cubes in primary colors that have been algorithmically deformed.

The field of digital art conservation is really fascinating. In the case of works like Computer Nude or Inner City Variation II, the institution has a print on paper that can be treated like any other print. But it’s still important to try to understand the larger technical systems used to produce the work, because that’s part of its meaning. We try to uncover as much as we can about the software programs and hardware systems that were used to make those prints. Acquisitions that entail taking possession of software or hardware are obviously even more challenging. We have to think about storage that is not passive but active. Hard drives are vulnerable to failure and should be replaced every seven years. You can’t just stick the file on a hard drive and put that in your storage and walk away from it and then go back to it thirty years later. You need to think about the programs and hardware you’ll need to access the file. This raises a whole host of interesting questions, and to answer them properly you’ll need to have extensive conversations with the artist to understand the nature of the work and how it should or should not change over time. Media art is sometimes called “variable” because it can look different each time it is shown. Even if you have a non-interactive artwork like a digital video file, you still have to decide whether to show it on a monitor or as a projection. There’s a big difference between a 27-inch monitor and a 75-inch monitor. If the video has sound, are you going to give your visitors headphones and make it a more personal, private experience? Or are you going to use speakers to amplify the sound in the space? What’s the appropriate volume level? Each of these choices impacts the audience’s experience of the work, even though the file itself may not have changed. One of the reasons I love working with media art is because it necessitates asking these philosophical questions about the essence of the artwork.

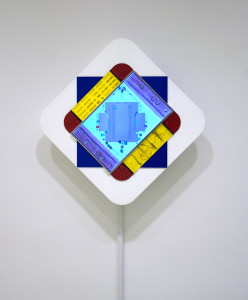

We have a work by John F. Simon Jr., a pioneer of generative art. It’s called Endless Victory (2005). It’s an Apple PowerBook G4 encased in acrylic plastic with custom software running on it. This is a software sculpture, because the software is indivisible from the customized framing. We have to think about conserving not only the files that are stored on this PowerBook but also conserving the PowerBook screen. We need a very considered plan for what happens when the computer starts to fail, including how it can be repaired or migrated to new hardware and software systems.

When a museum acquires a work of art, it promises to hold it in trust for posterity. The museum accepts the responsibility of acting as steward of that object until that object or the museum ceases to exist. I don’t know if people understand the magnitude of that responsibility. Storage is expensive. Conservation is expensive. The staff time of the registrars, art handlers, and guards who care for these objects is expensive. This is why museums don’t just accept every gift that’s offered to them. The process of acquisition is not simply a financial transaction, it’s a moral one. It is a very solemn responsibility, especially when it comes to living artists. We essentially are offering to help a part of them live on forever and be accessible to people in the future.

—As told to Brian Droitcour