A New Alchemy

An artist reflects on Bitcoin's status as digital gold and a substrate for her work.

Now in its third year, Art Dubai Digital has hit a stride. Art Dubai became the first major fair to present a digital art section in 2022, at the crest of the NFT bull market. I attended last year for the second edition, and it still looked rough around the edges, but in a way that felt exciting: the participants were working in an unfinished ecosystem, still figuring out what a digital art fair could be. This time Art Dubai Digital feels established, as if section curators Auronda Scalera and Alfredo Cramerotti have found a solution. In the first two years of Art Dubai Digital, the basement hall at the Jumeirah Mina A’Salam hotel was converted into a cavern, with black walls and accent lighting that made screen-based works pop. It looked a bit like a night club, or a media art festival. Now the walls are white, and natural light comes in from the side. This makes it a bit easier to imagine what the art would look like in a home. It also looks more like a standard art fair—just with a greater variety of media and genres clustered in a smaller space. In short, this year’s Art Dubai Digital makes the argument that collecting digital art is normal now. But spend enough time looking, and you can still find the moments where things feel off, in a tantalizing way, like you’re glimpsing a future that the present is struggling to catch up with.

This year’s fair feels like glimpsing a future that the present is struggling to catch up with.

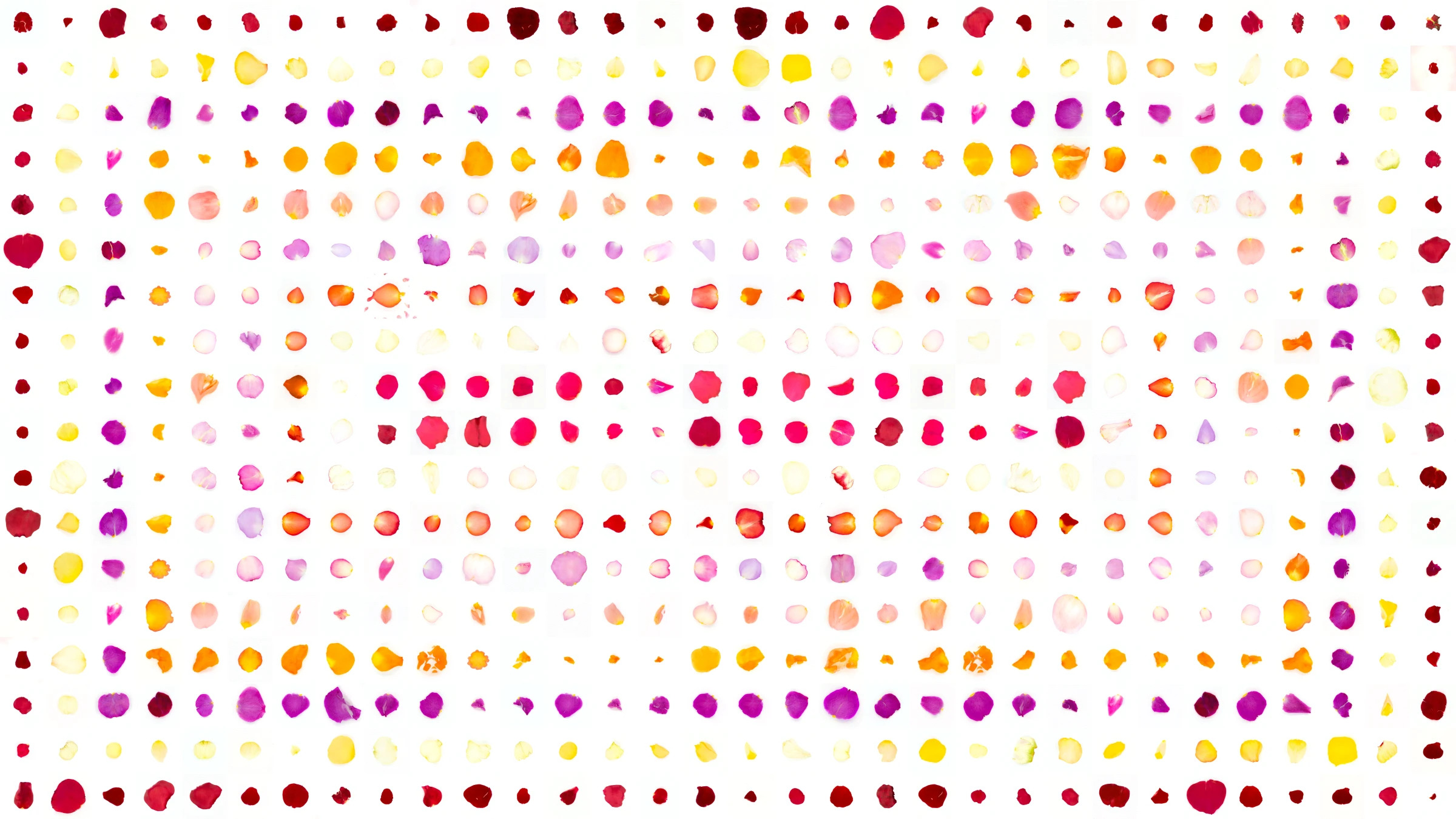

On entering you’re greeted with three strong solo booths. Sarah Meyohas, who made an early foray into tokenized art with her 2015 Bitchcoin project, is showing Infinite Petals (2023), an animation of fluidly morphing rose petals, with MakersPlace, the San Francisco-based NFT marketplace. The work is generated using a GAN from the archive of 100,000 petals she had photographed in 2017, some of which backed the second issue of Bitchcoin. In the opposite booth, London- and Mykonos-based gallery Hofa presents paintings made by Sougwen Chung in collaboration with robotics. For years Chung trained DOUG, as she calls her AI model, on her own pencil and ink drawings, but now she’s experimenting with oils to create brushy abstractions in blues and earth tones. Just past Hofa, the booth of Taex, a new London studio for small digital editions, is showing a trio of works by Angelo Plessas, who for over two decades has been making interactive animated websites that are by turns quirky and spiritual, alluring and haunting. High above the monitors on the booth’s walls hang quilted textile pieces with the iconography of his animations—yin-yangs, serpents, mudras. Right at the start of Art Dubai Digital you see three distinct takes on what digital art can be: Meyohas’s financialized conceptual photography, Chung’s human-machine collaboration, Plessas’s jaunty esoterica. There are more paintings and sculptures than screens.

Morrow Collective, a Dubai-based group of artists and curators, has populated a side gallery with a handful of ambitious curatorial projects, including “Revolutionaries,” a preview of an auction they’ve organized for Sotheby’s to celebrate a decade of art on the blockchain with ten works by early adopters: Meyohas, Rhea Myers, Kevin and Jennifer McCoy, to name a few. The works in the sale aren’t their genesis pieces, but ones made in the intervening ten years. I spent some time with a strange, funny animation by Nili Lerner, who released NiliCoin in 2014 as a way to fractionalize ownership of her physical works and share resale profits with collectors. Real Talk (2018–23) uses AI-generated imagery and text to simulate a conversation between Satoshi Nakamoto and Mickey Mouse about what it means to be a character representing a brand, whether Bitcoin or Disney, and how it feels to be an abstraction of an abstraction.

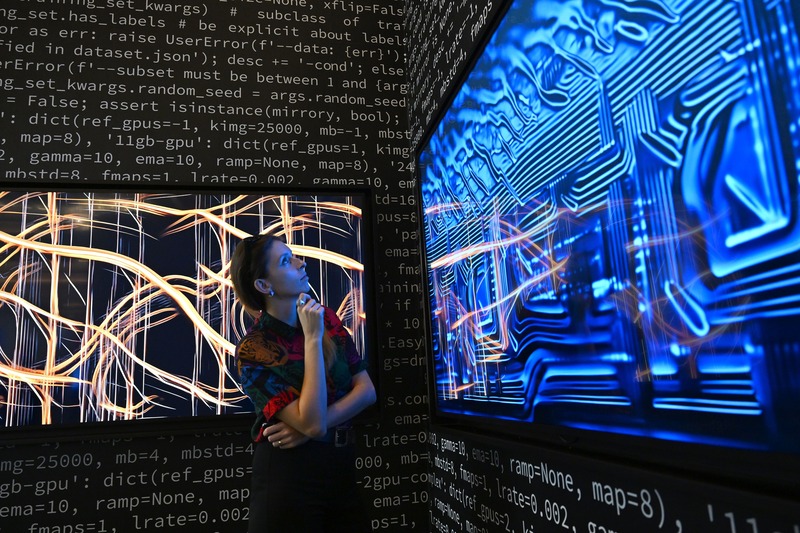

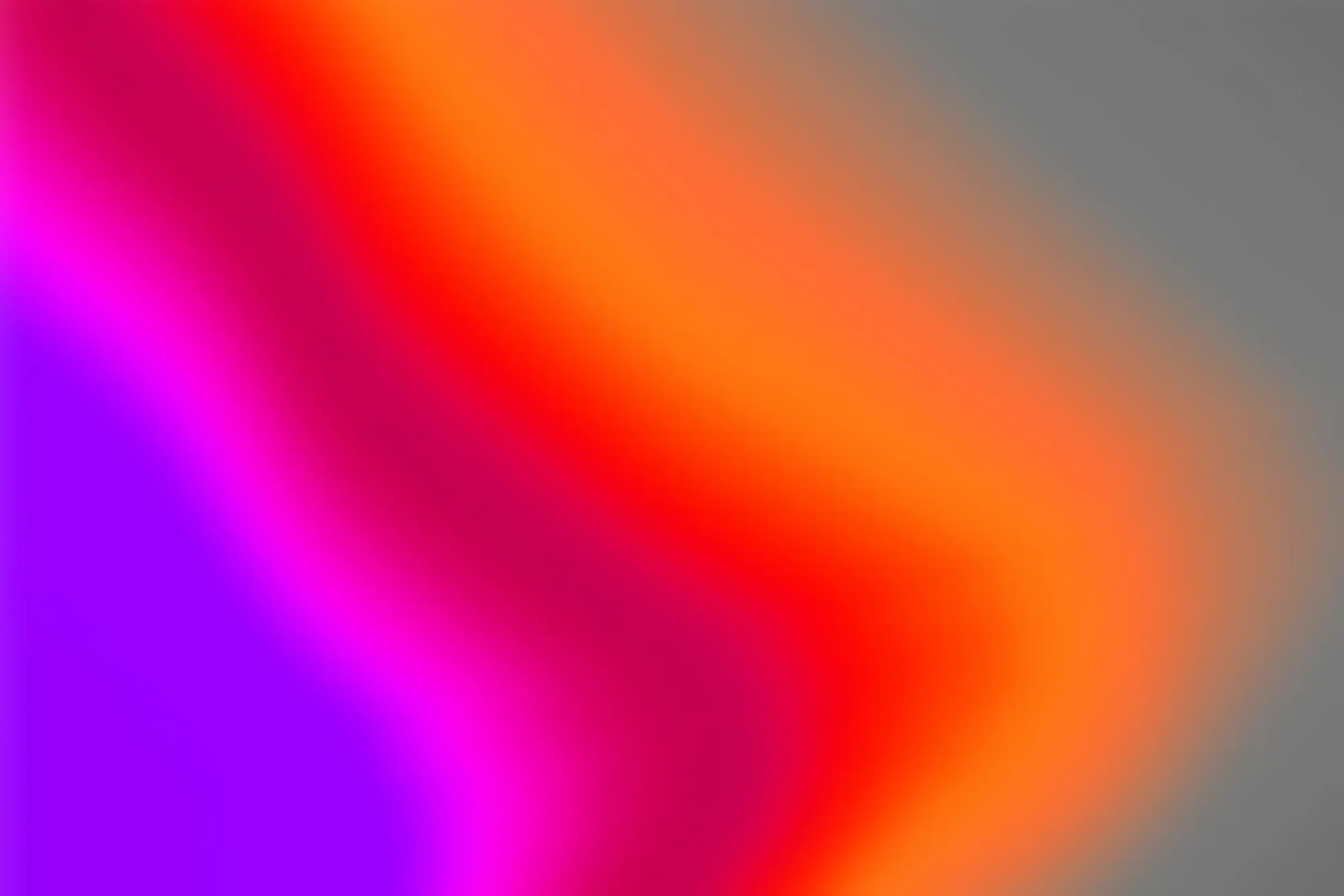

The ring of booths at the heart of the fair has an almost overwhelming mix of experiences—a charming AR animation by Monster Mike at Leila Heller Gallery, generative poetry by Ana Maria Caballero and Melissa Wiederrecht at Gazelli Art House, Ivona Tau’s demystification of AI art—that puts feathery morphing abstractions beside the code and hardware they came from—at 37x. Unit London’s solo presentation of works by Krista Kim includes two 2018 gradients that are so pulsating and luminous I did a double take before realizing they weren’t screens—they’re printed on Plexiglas and mounted on aluminum. The booth also has three screens with sparkling, spinning orbs from the artist’s “Mind Mirror” series. Kim makes the case for digital art’s role as a meditative focus, which offered a framework for thinking about some of the other soothing, minimal animations at the fair, like the one by Lee Lee Nam at the booth of Seoul’s Gallery Now, with glowing sigils and butterflies drifting through a field of waving grass.

There’s a fascinating juxtaposition in the adjacent booths of Italian company Cinello and the activist project Looty. Cinello produces high-fidelity digital reproductions of Renaissance paintings, and sells them with custom monitors fitted with gilded wooden frames crafted by a conservator at Florence’s Uffizi Gallery. Looty also makes digital reproductions of old art, but the purpose of these models of the Benin Bronzes and the Rosetta Stone (as discussed in a 2022 Outland article) is virtual repatriation, a way to bring looted art back to the land it came from. Looty’s goal is public access and social justice, whereas Cinello wants to make masterpieces available to private collectors. Proceeds of Cinello’s sales benefit the museums that hold the works, whereas Looty does a sort of piracy, even though both take advantage of digital technologies to multiply the presence of singular works.

Art Dubai Digital has its share of unremarkable render art, videos that could be cut scenes from forgettable video games, and AI art that already feels dated. But schlock and kitsch are present at any fair, as you can confirm while walking among the paintings and sculptures at Art Dubai. Incidentally, I counted three works of digital art at the main fair, all of them excellent. Almine Rech has three iterations of Ryoji Ikeda’s “data.gram” series, where live software simulates mysterious data visualizations, and Mario Mauroner Contemporary Art from Salzburg is showing Tatsuyo Miyajima’s Diamond In You (2011), an undulating, angular sculpture with numbers winking from tiny LED screens in its mirrored facets. A gallerist at Amman’s Wadi Finan told me the inclusion of a video piece by the duo Huniti Goldox was influenced by the presence of Art Dubai Digital. It’s a recording of a software-based water clock inspired by time-keeping practices indigenous to the Levant, and it hangs beside a series of aluminum casts of riverbeds to evoke an encounter with deep, long time scales.

If more digital art finds its way to the main fair at Art Dubai, will there still be a need for a special section?

If more digital art finds its way to the main fair at Art Dubai, will there still be a need for a special section? Two exhibitors at Art Dubai Digital told me they weren’t keen about being kept separate and planned to apply to the main fair next year. I suppose the success of Art Dubai Digital will be measured by its redundancy. If collecting digital art really becomes normal, then a digital section won’t need to exist. I don’t think we’ve reached that point, and subtle reminders of the reasons why are scattered throughout Art Dubai Digital—from the newness of the history of digital art’s financialization presented by Morrow Collective to the instability of ownership reflected at Looty’s booth, to the various works striving toward the experimental and experiential. Maybe someday soon it won’t be remarkable for an art collector to add an NFT to a wallet or hang a meditative animation beside a painting. But that future isn’t here just yet.

Brian Droitcour is Outland’s editor-in-chief.