The Outland Review, vol. 2

Andreas Gysin and Sidi Vanetti's numerical art, the collaborative generative art project "N=12," Takakura Kazuki's AI installation, and Mark Fingerhut's malware ride reviewed in brief

Ever since the release of MacPaint in 1984, image-making software has allowed—even encouraged—users to simulate the effects of older artistic mediums. Programs offer a variety of digital brushes that leave hair tracks in blocks of colored pixels, and digital pencils for drawing lines of varying thickness and quality. Many have incorporated filters that can be added to images to make them brushier, softer, more impressionistic.

For centuries, art critics have attributed to visible brushwork a vitalist force.

What’s the point of making a jpg look painted? Where does this desire for painterliness come from? For centuries, art critics have attributed to visible brushwork a vitalist force. The trace of the artist’s hand is an imprint of the artist’s soul, identifying the work of art an expressive act. The brush is a kind of spiritual prosthetic, and in Photoshop or MS Paint, this prosthetic undergoes further mediation and abstraction, programmed with skeuomorphic properties so it can still be recognized as a conduit for expression. It’s operated via mouse, and its effects can be changed by the toggling of buttons and adjusting of sliders rather than shifts of physical pressure. Of course, skilled digital painters, like Craig Mullins and Lethabo Huma, don’t simply demonstrate a program’s ability to produce painterly effects. These artists create an image environment where digital brushstrokes aren’t immediately legible as software tools, just as in a physical painting the brushstrokes become more than the movement of a wet brush across canvas.

Generative artists often write their own image-making programs and let them run with some degree of autonomy, rather than working with the tools of readymade software. While many generative artists explore properties specific to the digital environment, others simulate physical media. Scroll through projects released on Art Blocks, and you’ll find plentiful examples of both approaches. Jeff Davis’s Color Study (2021) considers how color theory functions in the light of the screen, and the compositions of Kim Asendorf’s Cargo (2023) map out ever-changing movements of pixels. But Melissa Wiederrecht’s Sudfah (2022), inspired by her interest in Arabic calligraphy, depicts splotches of ink pooling and spilling around energetic black lines on backgrounds resembling linen. William Mapan’s Anticyclone (2022) evokes the muted dryness of colored pencil on aged paper. The animations in Watercolor Dreams (2021) by Matt Jacobson (aka NumbersInMotion) represent the translucent flow of water-based pigment. In standard image-making software, even with the different brush effects, everything is neat. The layer tool keeps the image’s planes distinct. Colors don’t run. Generative painting teaches the machine to approximate the spontaneity and messiness of the studio.

Generative painting teaches the machine to approximate the spontaneity and messiness of the studio.

While image-making software simulates the gestural effects of painting to bring some humanity into digital art, generative painting delegates the gesture to the program. The generative artist instead asserts their perspective by redefining the relationships among the simulated materials and the coded gesture, modeling the physics of liquid and gravity with more verisimilitude than mass-market software. The gesture of the generative painter can be read in how those relationships are defined.

The outputs of Metropolis (2023)—another Art Blocks project by Michael Kozlowski, aka mpkoz—resemble pleasant painterly abstractions, shapes and volumes rendered in jewel tones with even gradations of hue. “Oil” and “watercolor” are traits that Kieslowski assigned in the code, and in the works these simulated textures rub against each other in ways that would be difficult, or impossible, to achieve with physical paint. This confluence of simulated mediums gives Metropolis an uncanny serenity, exaggerated further in some outputs by lacy overlays of white lines with a starkly digital sharpness. Each one of the five hundred still pieces is accompanied by an animation that shows the process of its creation. Over the course of five minutes, areas of the blank “paper” are filled in, one or two or three at a time. While in the final appearance the colors seem to blend, these “live” versions reveal how the gradients are coded into each stroke, the result of Kozlowski’s design for the automated brush. Environmental properties like the movement of translucent, watery pigment are folded into the coded gesture.

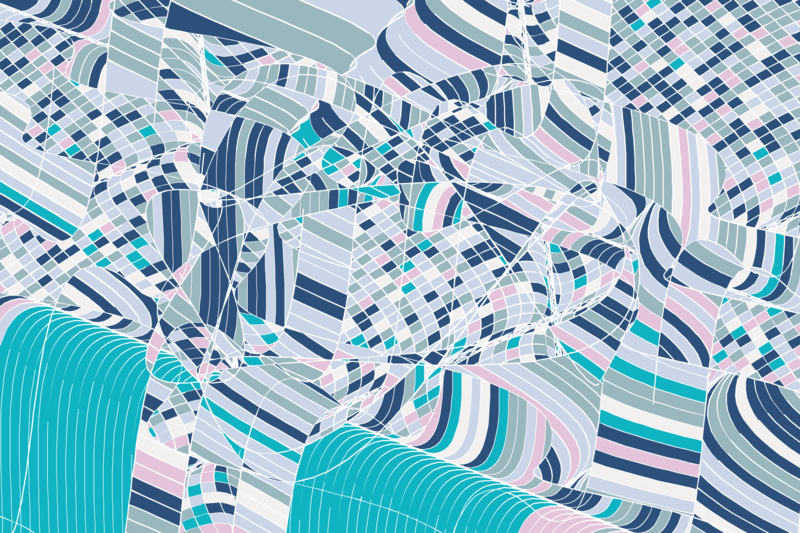

Licia He’s generative painting bridges simulation and physical mediums, crisp digital images and studio mess. Endless Monologue (2021)—released as part of “-Graph,” a Feral File exhibition of artists who use plotters—makes the juxtaposition explicit. The work was first issued as an edition of thirty mosaic-like digital compositions, with curving fragments of color divided by intersections of sweeping white lines. These look a bit flat, because of the neatness of their organization and the uniformity of the palettes, dominated by dull tones and color wheel adjacencies. But the collectors who purchased these received a corresponding plotter painting on paper. Most artists who work with plotters use pens, but He equips the robot arms of her rig with watercolor brushes, making her process wet and risky. Her palettes look more compelling on paper, where water and brush hairs blend and modulate color. The white lines vanish in the bleeding edges of the plotter’s brushstrokes. The digital outputs of Endless Monologue don’t attempt to simulate an environment of physical materials, but He transposes the coded gestures to a physical environment. Even as He unleashes the computer on physical paints, she maintains the position of the generative painter: that expressivity lies not in the gesture itself so much as the parameters determined by the artist who built the system that produces the outputs.

Expressivity lies not in the gesture itself so much as the parameters determined by the artist who built the system.

Sparkling Goodbye (2023), He’s project for the last Bright Moments event in Tokyo, similarly combines simulation of painterly texture with computational hard edges. The palettes in this collection are bolder and richer than those of Endless Monologues. He still favors mosaic-like compositions that piece together uneven fields of color, but here she renders them in broad, thick strokes, with brushy surfaces. Zoom in to view the image more closely, and you’ll find more texture in the ground: translucent layers of color and arrow-straight striations that give the image an even rhythm. These details are like a quiet assertion of the expressive properties of the machine-made grid, made more poignant by through the juxtaposition with simulated gesture.

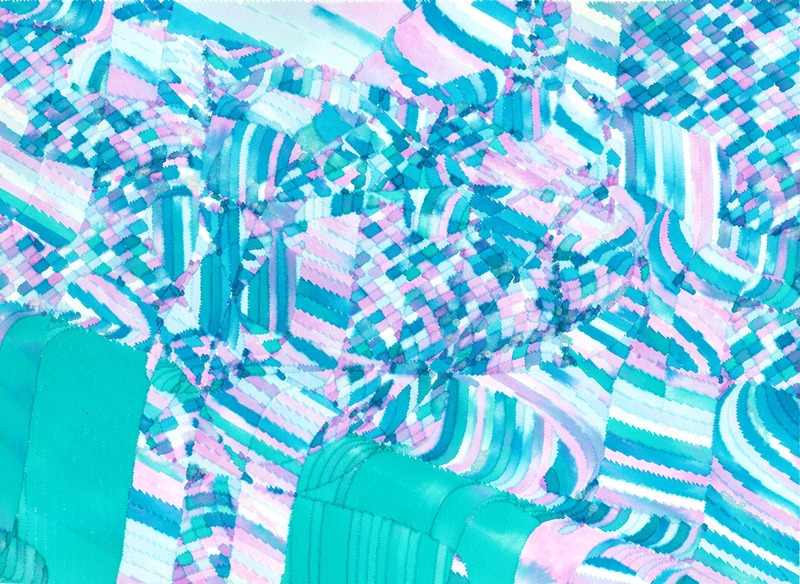

Andrew Benson, aka pixlpa, calls the works in his “Grinders” (2022) series digital paintings, though their appearance does nothing to simulate physical mediums. Each of the hundred pieces in the series is an animated gif with a nervous rhythm. Chunky blobs and thick, vivid strokes of color jostle against each other in syncopated loops. The palettes are garish, featuring magentas, fluorescent yellows, wan greens and browns, and other tones rare or nonexistent in nature, as if to underscore the artifice of the digital medium. Benson released the project independently, and on the grid of the website he built to display it, you can see how the palettes are engineered as combinations, each one labeled with a name: “Acid,” “Enamel,” “Martian,” and so on.

The software Benson wrote to make “Grinders” is a variation on a program he has been writing and rewriting for over a decade. His programs are inspired by, and sometimes incorporate patches of, MaxMSP—a software commonly used for performances by digital musicians, to generate live effects and connect visuals to sound. Benson is drawn to electronic music as a genre that finds expressive uses for digital tools: loops and recursions, those fundamental operations of computer code, create richness in electronic compositions, adding depth as they contrast repetitions and variations. His digital paintings translate those effects into color and gesture. In Benson’s painting programs, the user makes a mark, which is then captured by the program and repeated. Subsequent gestures trigger echoes and reactions in previous ones; sometimes they “re-paint” that color and shape, twisting it into a new form. I say “user” here as a convention of describing a relationship to the program; Benson is usually the only user of his software, though his website has a version that visitors can play with, to get a sense of how his process works.

To describe generative art that simulates physical media, I’ve set up an opposition between image-making software’s imitation of individual gestures and the generative artist’s recoding of relationships to make an environment that simulates particular effects. Benson is doing something somewhat different. Like other generative painters, he’s coding responsive environments. But instead of simulating the painter’s studio, his programs draw out properties inherent to the digital medium, and makes them responsive to gestures made by the user’s hand. Colors bleed together, but not in ways that imitate the mixing of physical pigments. They braid and collide as pixels to record the artist’s expressive movements. Benson holds onto the humanist belief in the primacy of the gesture. But he combines it with a belief in the expressive properties inherent to his tools.

Brian Droitcour is the editor-in-chief of Outland.

Disclosure: the author owns two works by Benson, from series other than the one discussed here.