History in your hands

A major exhibition about NFTs at Kunsthalle Zürich invites visitors not just to contemplate but to curate and collect.

The works of Atlas, a new generative NFT collection by Eric De Giuli, are a bit like dynamic Powers of Ten paintings. A 1977 experimental film by Charles and Ray Eames, Powers of Ten opens calmly with an overhead shot of a couple at a picnic before zooming out 100 million light years from Earth into lonely, distant space. Zooming back in and further, the camera lands on a single proton, described as the edge of human understanding and displayed as a cluster of colored dots that jitter and smash. In the film, human beings aren’t the center of the universe, nor are they even one of its constituent elements. People are fragile, floating helplessly somewhere in the middle.

Parts of the piece that interact so strongly at the most infinitesimal level connect to form structures only visible at other scales.

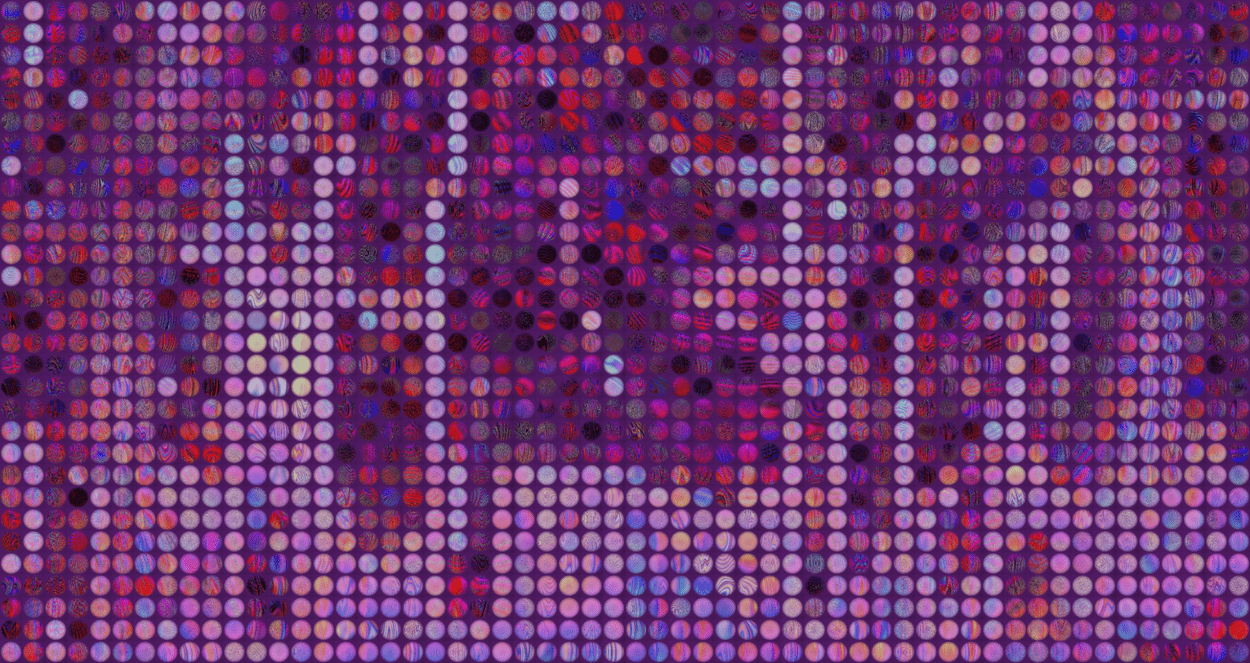

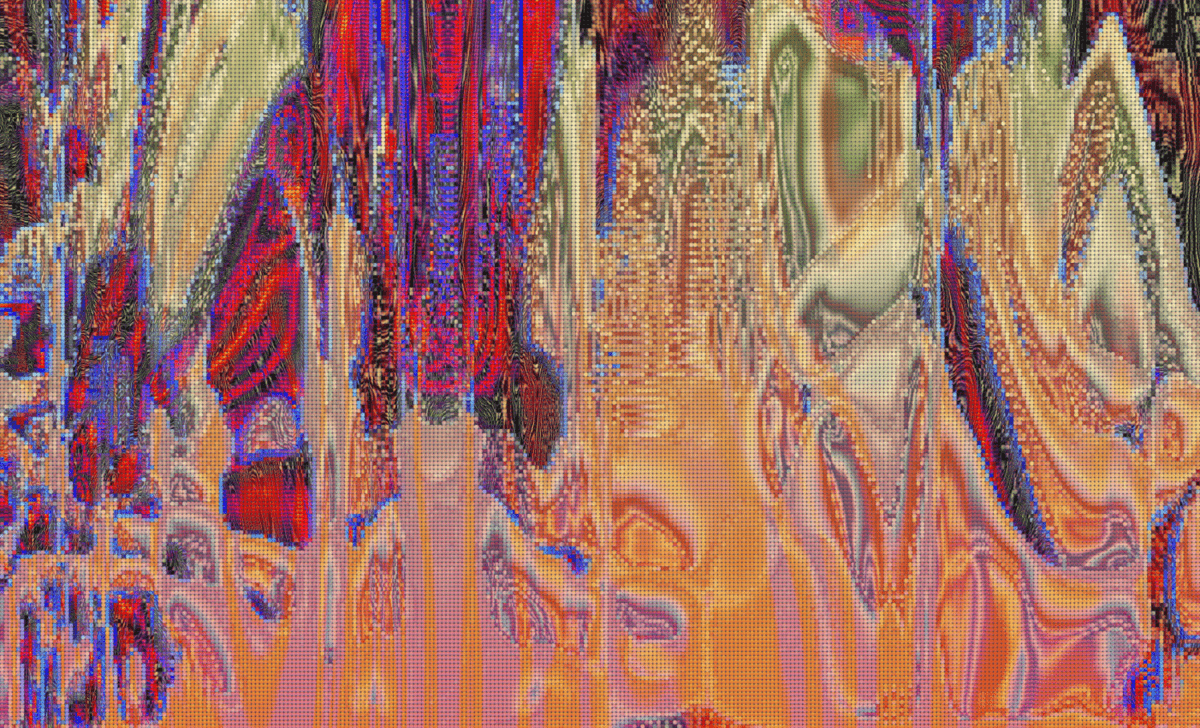

Instead of a picnic, the starting point of each Atlas piece is a shimmering, abstract mosaic that moves. Cleanly dividing the canvas is a grid of circles or squares, cells whose well-defined borders don’t delimit so much as they obscure—like light refraction—the gentle shapeshifting of organic-feeling forms that pass through them. Many of these initial compositions are beautiful in their own right. Those with a more muted, naturalistic palette might loosely evoke a close-up of a flexing lizard’s leg or swaying tree branches in a snowstorm at night. But the more conceptually and technically exciting aspects of Atlas reveal themselves only when you interact.

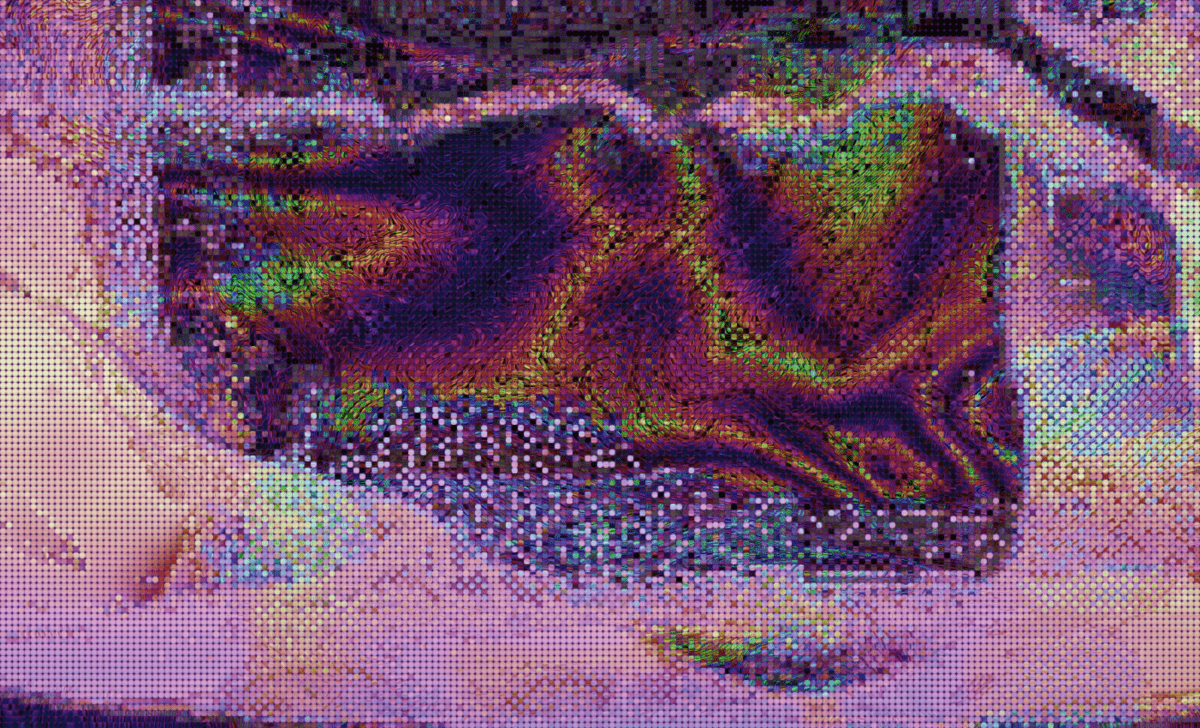

Resource-friendly JavaScript allows you to smoothly zoom into the artwork down to the level of its metaphorical quark. Unlike a flat image, where zooming eventually fills your screen with a few coarse pixels, the closer you look at Atlas, the more violent and chaotic it seems. The original composition’s tiles, which might at first have appeared to be solidly colored, reveal themselves to be comprised of flickering interference patterns of changing hue, value, and chroma. Competing waves of patterns at multiple scales crash over and into one another in an orgy of color-swapping and shader noise. Nothing at any scale is entirely stable.

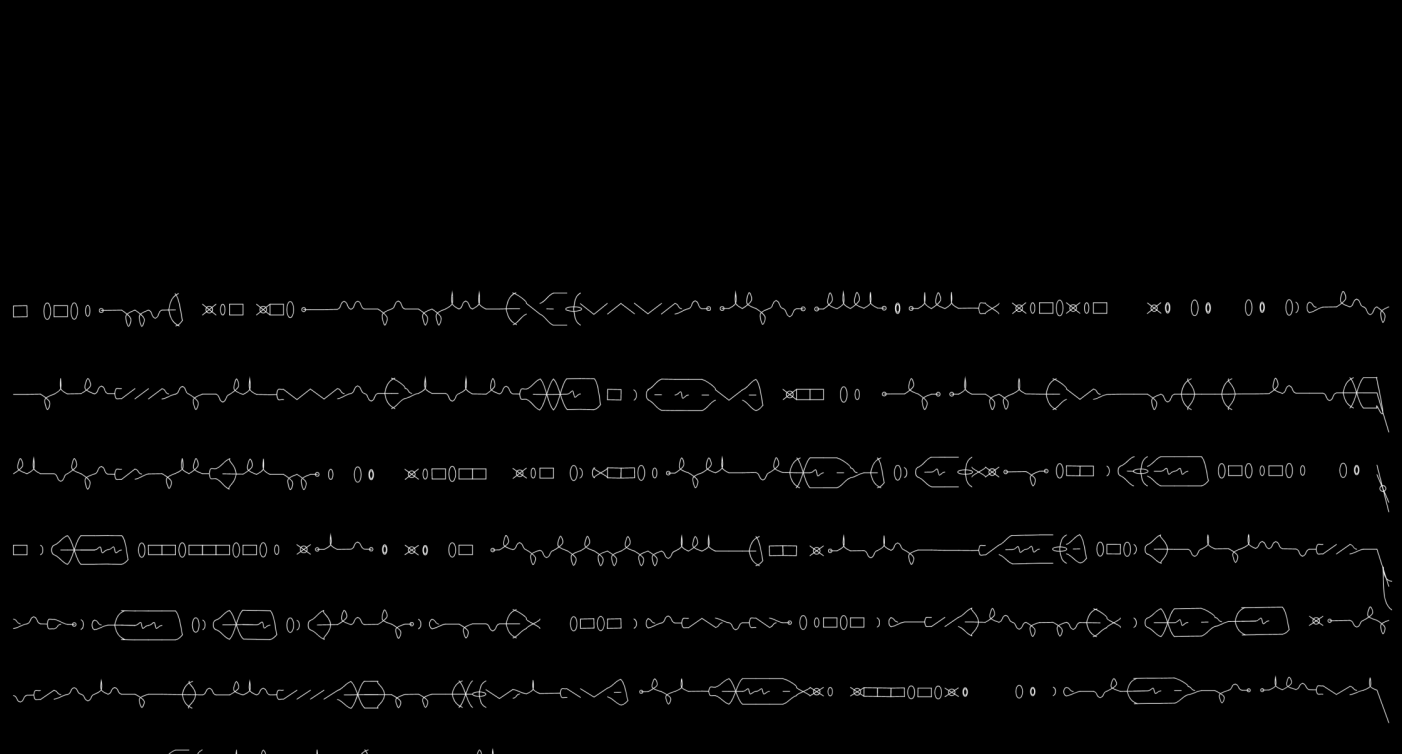

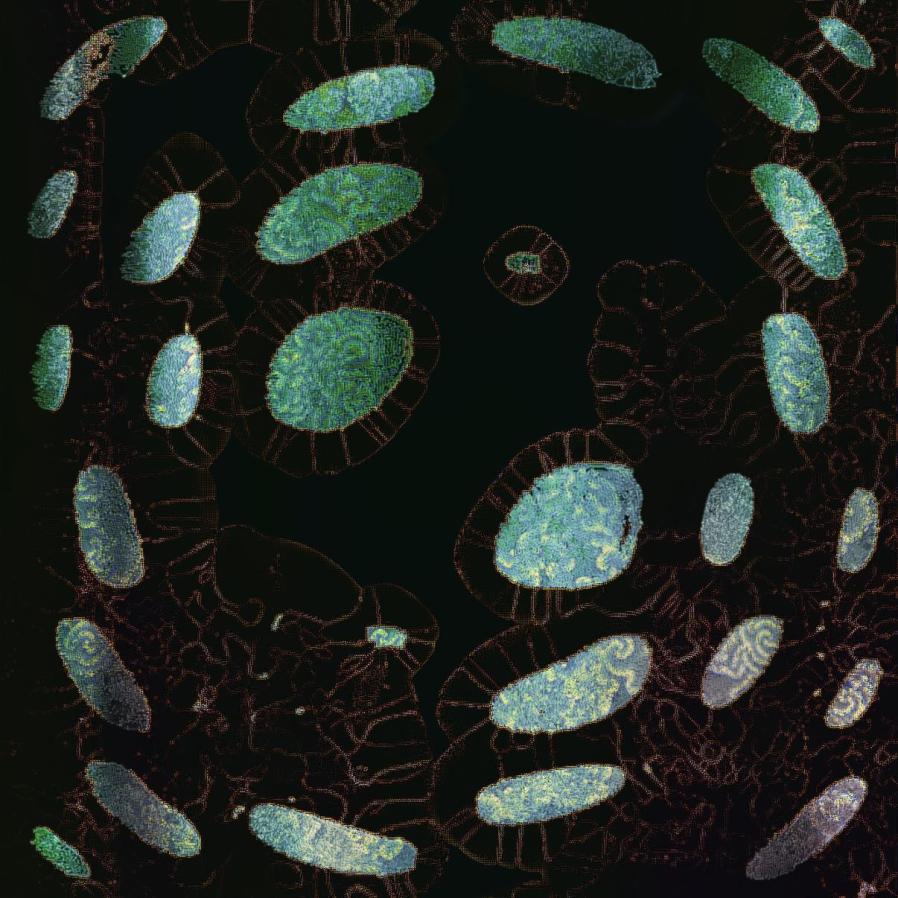

Besides being an artist, De Giuli is a theoretical physicist, and his NFTs often demonstrate how complex systems contain self-organizing elements. His first series was Alien Tongues (2021), which imagined messages from an alien civilization as spectral scratches organized by geometric syntaxes. Calian (2023), released on Art Blocks, is perhaps his best-known; its dynamic abstractions resemble a time-lapsed video of bacteria growing in a Petri dish. Atlas, De Giuli explained in a phone call, continues his tradition of letting his work speak to his day job and vice versa. “There’s a huge history of artists exploring this idea of the sublime—man’s smallness compared to nature,” he told me. “But today, we’re in this inverted scenario where many of our issues aren’t really about our smallness but our largeness. Considering what we can do with nanotechnology and biological engineering, we are in a literal sense very large.”

Unlike Powers of Ten, which placed man at the center even as it seemed to question his importance, there’s nothing particularly human-looking in this work. That might make Atlas a less obvious method of considering our place in the cosmos, but perhaps it’s also for the better. The figures in De Giuli’s Phantoms (2021) were awkwardly mannequin-like; his most exciting work, Atlas included, tends to be his most abstract. But whether the zoomed-out Atlas outputs vaguely resemble the dripping liquid crystals in a cracked laptop display or something more biological, there is undoubtedly something natural about how they’re put together. It’s a fitting effect for the work of a theoretical physicist: parts of the piece that interact so strongly at the most infinitesimal level connect to form structures only visible at other scales. And it’s a nice way of thinking about digital art. Atlas reimagines that common idle practice of zooming in on some image until you can’t anymore, so that the things you see up close are alive.

Duncan Cooper writes about art and saints.

This essay is presented in partnership with GrailersDAO, the producer of Atlas.