What's Their Game?

The NFT market has spawned a new cultural form that has elements of games but not their rules.

We can think of the blockchain primarily as a kind of clock. Bitcoin and other blockchains are stores of value, but they cannot store value without first delineating and recording time. As the original 2008 Bitcoin whitepaper explains, the basis for a decentralized digital currency relies on an accurate and indisputable record of the order of transactions. This ever-growing chain of records functions as a replacement for the authority of a bank or government. What Satoshi Nakamoto refers to as the “double-spending problem,” the threat of one piece of digital currency being sent to two destinations at once, is solved by a shared chronology of transactions, stored publicly on a peer-to-peer network, verified by a ridiculous number of computers solving big math problems. It’s an odd system, but it ultimately succeeds at its task: determining and recording a chronology of who owns what, and when they own it.

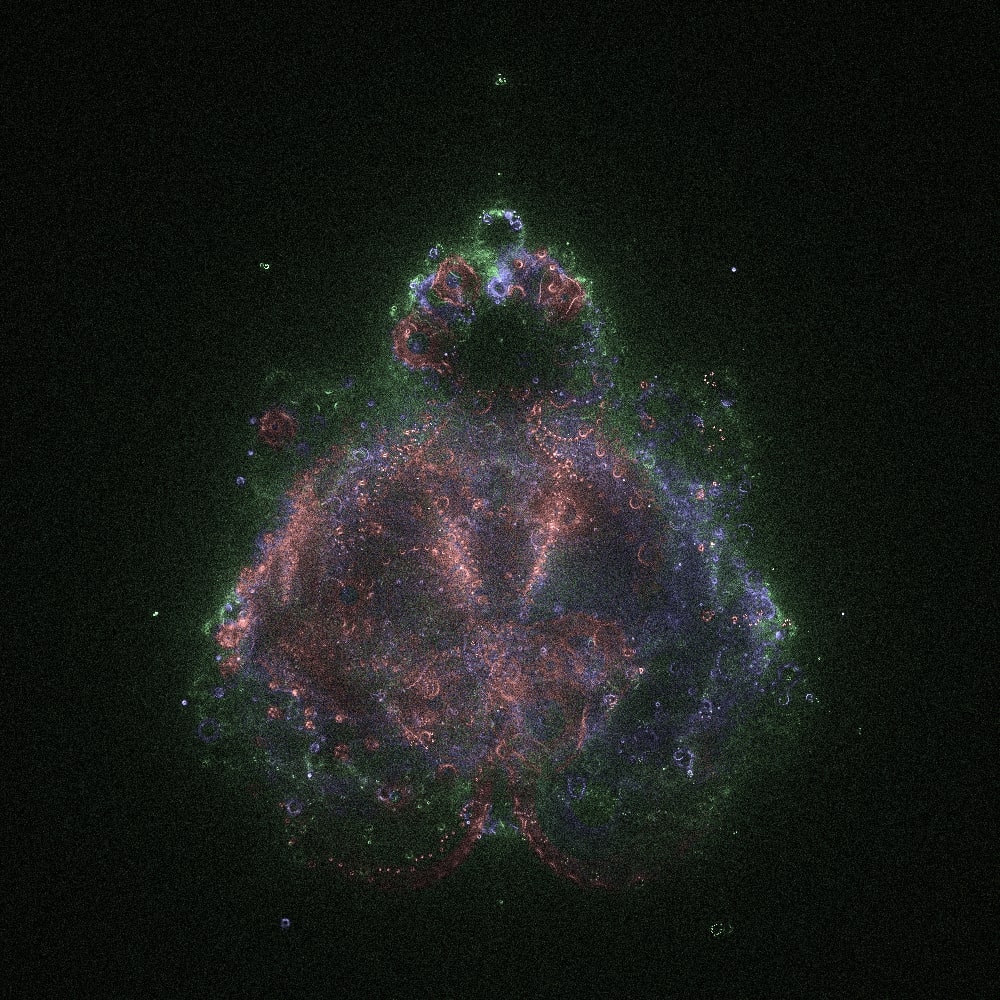

It didn’t take long for artists to take interest in this strange new form, and soon enough blockchains became ledgers for more than just time and value, but for artworks as well. Of course, there are a variety of ways to make art on or about the blockchain; recently, Bitcoin Ordinals have begun to flourish. Ordinals are a way to log the creation and ownership of artworks on Bitcoin that sits closer to the conceptual origins of the blockchain itself—and its reliance on chronology—than other NFTs. The Ordinals are rooted in small notes appended to the ceaseless production of Bitcoin transactions. “All at Once,” curated by GrailersDAO and Singular and hosted by Verse, is a digital exhibition of Ordinals that invites artists to begin with the notion that blockchains exist to delineate chronology. The exhibition is an ideal occasion to consider the intersection of art, the blockchain and time—and how artists can create meaningful problems in the context of rigid technological solutions.

Art history has long been fixated on chronology, perhaps to a fault. Historians debate which artist did something first, where an idea began. Accurate chronology owes its allure, at least in part, to the desire to map how artists influence one another, how schools of thought form, and how hotbeds of creativity take shape. But there’s always a fog in history. The mess of influences and interactions can never be fully untangled. This is part of the romance and, frankly, the fun of art history.

Art history has long been fixated on chronology, perhaps to a fault.

And yet, compared to the dusty tomes of art history, inscribing artworks on a blockchain provides a crystal-clear provenance. This is particularly evident with Ordinals, whose identifying inscriptions are appended to the regular march of hashes and verifications. The certitude of sequence and provenance would seem to solve a longstanding problem of art history: now we always know the exact order of things. But this clarity comes with a cost. There’s a danger that mystery and romance could be explained away by the cold machinations of code. Technology exists to solve problems, while art exists to create them. The challenge for artists working with the blockchain is to make organic, unruly work in the context of the technological solutionism that undergirds the crypto movement. How can artists create interesting problems in a culture obsessed with solving them? How can artworks made of deterministic code contain genuine surprises?

Time is not a new subject for artists. One could mention the allegorical paintings of time as a winged figure with an hourglass on his head, or Monet’s repeated renderings of the changing light on the cathedral at Rouen, or Christian Marclay’s 2010 blockbuster video installation The Clock. But there are two related works I’d like to highlight here because they not only consider time, but also wrestle with the way that technology can solve one problem only to create another.

“Untitled” (Perfect Lovers), from1987–90, is one of the most famous works by the conceptual artist Félix González-Torres. The piece consists of two identical store-bought clocks hung side by side on the wall, their sides just touching. When they’re installed the clocks are both set to the correct time, but over the course of the exhibition they will drift apart. At first the discrepancy is barely noticeable, maybe a second or two. But the clocks are cheap, and their battery life is short. Gradually they fall further and further out of time. “Untitled” (Perfect Lovers) is about the imperfection of our experience of time, and our imperfection to each other. Even perfect lovers drift apart eventually. Like many of González-Torres’ works, “Untitled” (Perfect Lovers) alludes to his relationship with his partner Ross Laycock, who died of complications from AIDS the same year the work was made. González-Torres died of the same illness, five years later.

In 2002, a subversive and playful designer named Tobias Wong created Perfect Lovers (Forever). It was a pair of white clocks that looked identical to González-Torres’ work, but Wong’s version included radio transmitters in the clocks that were capable of syncing with the US atomic clock. This pair of lovers would stay in step second by second for more than a million years. This wry gesture was typical of Wong’s work, which often riffed on other artists in sometimes sardonic ways. Wong’s life and work were also unfortunately cut short, when he died by suicide—his partner and many friends believed it was an accident that took place while he was sleepwalking—in 2010.

On one hand, Wong’s version ruins the original work. The imperfection of González-Torres’ simple store-bought clocks is what makes them such poetic readymades. Sure, they’re mundane objects, but their flaws are what make them stand-ins for imperfect people, and an illustration of imperfect love. Wong takes the problem of Perfect Lovers and does his level best to solve it. No more drifting out of sync, these two clocks will be together forever. By using technological precision to root out the poetics of the original, Wong instead mounts a critique of technological solutionism itself. Which problems do we actually want technology to solve? Do we really want perfect machines, or perfect lovers? If we achieve what technology seems to be after, we might find that the result would make us less human.

Which problems do we actually want technology to solve?

Returning to Bitcoin Ordinals, artists making work in this way are wading into a particularly heady and politically charged culture of technological solutionism. For now, Bitcoin exists in a quantum state of simultaneous success and failure. On one hand, it does what it purports to do. On the other hand, it has not taken over—or even radically altered—the global financial system. At this point it’s still a sideshow, a curiosity. Is it on its way to becoming something much bigger? Maybe, maybe not. But even if it remains a sideshow, it’s still something that artists should engage with critically, because its existence tells us something about this moment in history, and it may even alter the way we think about and record history from this point forward.

Kevin Buist is a critic, curator, and filmmaker living in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

This essay is presented in partnership with GrailersDAO. The artworks illustrated here are from “All at Once,” an Ordinals exhibition curated by Grailers DAO and Singular and presented by Verse that launches June 17.