Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley & R.I.P. Germain

The two artists discuss their use of gameplay as a strategy to make the viewer engage with the difficult questions raised by their work.

The whitepaper that terra0 published in 2016 opens with a provocative question: “Can an augmented forest own and utilize itself?” The authors argue that, since blockchain technologies like smart contracts allow nonhuman entities to administer capital, they can be used to bestow natural ecosystems with legal personhood. Through connections to various sensors and measurement devices, the forest would determine what it needs to thrive, and sell off expendable trees so that it may acquire resources for further growth. While the complexity of a forest makes the whitepaper’s proposals extremely difficult to realize, terra0’s members have tested the concept through installations where plants interact with people via smart contracts to optimize their environments. One such installation, Premna Daemon (2018), was included in “Proof of Work,” an exhibition curated by Simon Denny about experimental uses of the blockchain. As part of Denny’s tenure as Outland’s guest editor, he invited Paul Kolling and Paul Seidler, two of the authors of the terra0 whitepaper, to revisit their early encounters with him and reflect on how terra0’s work has developed since. The three also discussed the differences between code and law as means of managing social and proprietary relationships, and the importance of grounding technology’s abstractions in the historical specificity of the real world.

SIMON DENNY You were part of the exhibition “Proof of Work,” which I organized at Schinkel Pavilion in Berlin in 2018. That was my first attempt to bring together interesting art-adjacent things being done using cryptocurrencies, and to frame them in relation to exhibition-making. I invited a number of dialogue partners who in turn invited projects they were excited about. I was trying to respond to how the blockchain world was structured, with this sense of distributed decision-making and drawing on knowledge bases through networks. I didn’t want to be a curator standing at the center—I wanted it to be more horizontal. I had met you two through Trust, a “conspiratorial utopian coworking space” in Berlin. I had reached out to you guys earlier, but I asked you to participate with your project and nominate some others. You had a concept you were working on, and you had to come up with a way for it to operate in an exhibition environment such as the Schinkel. Could you talk about how you met that challenge?

PAUL SEIDLER We wrote our first whitepaper in 2015–16and when you approached us we weren’t sure where the project was going. There was interest from very different directions, VCs on the one hand and art institutions on the other.

PAUL KOLLING At that time we were just about to launch Flowertokens (2018), an experimental test case in the front area of Trust, focused on creating a trading platform for a set of physical flowers, to see how market dynamics change if the underlying assets are undergoing constant growth. There was a rack where a hundred flowers were planted, and a camera collecting data from the flowers, which would be attached to ERC-721s. This was when the first NFTs were being created. CryptoKitties weren’t what you’d call mainstream, but there was some interest and adoption. Flowertokens asked: what would happen if the NFT was actually bound to a living entity, like a flower? We came to think of it as an art piece, but we didn’t know how it could be included in “Proof of Work.” The project was still running, and we wanted to take it seriously as an experiment.

SEIDLER It was also technically quite impossible to move, because it took a long time to build and configure the environment and the cameras.

KOLLING We could have done a second version, but that would have changed the nature of the first one. We would have collected too much data before even analyzing the results of the initial experiment. So there was an internal decision to make something new, which became Premna Daemon (2018). It originated from a discussion about designing an experiment specifically for a museum space. For this we set up a contractual relationship between a bonsai tree and the institution that covered all the needs of the plant. For example, it needs to be watered, it needs some UV light, it needs to be pruned and taken care of. These services would all be done by the employees, in exchange for a payment by the bonsai tree. We gave it a wallet. And visitors could donate money. The work tested how people would react when they saw the needs of this living entity. Would they make a donation knowing they would get nothing in return? This is quite interesting if you look at the blockchain token landscape now. Literally every transaction comes with some receipt, and most of the time there’s a claim that this receipt might be very valuable at some point.

DENNY One of the things about terra0 that resonates strongly with me is how it started as a whitepaper, produced as a conceptual art proposition. The whitepaper designates the territory, no pun intended, that you’re interested in, and then you do these iterations of it. What does it mean to make a whitepaper as a declaration of artistic intent—a manifesto, in a way? What does it mean to reach these various outcomes from that starting point?

KOLLING A whitepaper is a great medium because you can start off with big, complicated ideas with literally no budget. This was quite essential for us. And if you then publish it, you get feedback, which lets you realize what’s worth investigating more thoroughly. But to test the claims we made in the whitepaper, we would have needed an enormous amount of funding to buy a forest, hire a team to develop a tech stack, hire lawyers, and so on. To get things going without these funds, we decided to fragment our fields of research into smaller aspects and create feasible experiments. One was Flowertokens, and the other was Premna Daemon. A tree, a corporation, a person, our work for last year’s Carnegie International, is also part of this series of test cases.

SEIDLER The first whitepaper was about how a forest augmented through automated processes could become a shareholder of itself—the only shareholder of itself, essentially. As a model, the forest should function like a corporation that, enhanced by technologies such as lidar scanning and satellite data infrastructure, can collect data and use that data to determine which trees to sell to earn money to pay for its own maintenance. The forest here is both the actual piece of land and the technological, social construct built around it. It came out of research into autonomous agents and the first conceptions of DAOs, which were quite different from how DAOs are perceived now, as a multisig contract with some social space attached. DAOs as initially described by Vitalik Buterin sound more like automated corporations. How could a program administer capital with just a few inputs? This lineage of ideas led us to an almost technocratic approach and many questions to answer. How can a flower or other ecological entity be represented on a ledger? How could governance work in these systems? How could maintenance by different actors be programmed in a decentralized way?

KOLLING At first we didn’t think of the Flowertokens as artworks. We treated them as a tool for understanding the dynamics and functionalities of these markets.

DENNY I always thought of them as documentation of a performance, coming from the art historical side. With conceptual art there’s always a conversation about where the art happens: is it in a photograph, the performance, or the tension between these?

KOLLING We just had a conversation about the aesthetics of eco art and how hard it is to understand, because you have such a strong image of all the documentation and artifacts displayed in gallery spaces. But it’s really hard to say what was part of the artwork at its time of origin. It’s the same with Flowertokens, which were elevated to artworks in 2021, when they got rediscovered by so-called “NFT archaeologists” and were suddenly treated as something very valuable and traded for high prices.

DENNY And packaging, right? You redeployed the tokens at the NFT archeology moment, when these early experiments had value assigned to them. I know a number of projects, including yours, that responded by deploying an asset form that was more fungible in the environment at the time. So instead of associating a token with a plant, you attached time-lapse video documentation of the flowers growing, which you produced in 2021, to the token. The NFTs were more of a package.

SEIDLER Yeah. Another interesting point is that ERC-721was not originally intended to be for art, but rather to map other assets like real estate, land ownership, and debt on-chain. These cases have not been put into use, mainly because of legal issues. Meanwhile ERC-721 became the de facto standard for what an artwork looks like on the blockchain.

DENNY That’s super interesting. Around the same time, Decentraland, one of the earliest digital land projects, was being developed. I came across it in January 2017, when I visited New York to be part of the Ethereal meetup at ConsenSys, a software company run by Ethereum co-founder Joe Lubin. There I met Sam Hart, whose wallet became very important for the NFT archaeologists. He was an amazing early curator in the blockchain art space, and now works with Cosmos. For the meetup he curated a little show where I first came across the work of Rhea Myers, and met Lars TCF Holdhus. I had a board game I’d made in the show. It was all installed inside a giant inflatable bubble made by the FOAM collective, which I later included in “Proof of Work” as a key aspect of the installation. The meetup also featured a big display about the development of Decentraland, which talked about the potential use case of token formats for representing ownership and digital land. That was all happening at the same time as terra0 was developing and being prototyped for these other spaces.

SEIDLER FOAM had the idea to have ERC-20 tokens for every GPS coordinate in the world. That never happened, but there is definitely a conceptual connection between ERC-721 as a format and claims on land.

DENNY FOAM is still active today, but their earliest project involved issuing a token to support crowdsourcing ideas for urban development. You would use a map to propose things that should happen in particular spaces, and the tokens would fund whatever the most popular things were on the token curated registry—a reallyinteresting concept that never got built.

Premna Daemon was about the commons, the unpaid services that maintain the ecosystem. You were asking people to spend money and get nothing in return. There was no speculative receipt for that particular performance. But you tried that later on, right? Seed Capital at Art Dubai last year was a really interesting deployment of terra0 in a very different environment, when NFTs were much more of a thing, but still operating in this interesting place between the autonomous forest corporation and the art world.

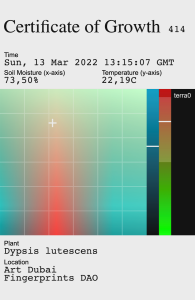

KOLLING The mechanics of Seed Capital were an inversion of those of Premna Daemon. The project was instigated by Fingerprints DAO, which is as far as we know was the first collecting DAO to be represented at a traditional art fair. They approached us and very generously offered their booth at Art Dubai as an exhibition space, and we were interested in appropriating this highly commercialized space for one of our test cases. How can we use NFTs as a game mechanic to make sure that people take care of a plant? The whole sculpture was produced on-site. We sourced a local plant from Dubai. The plant was then fitted with sensors that could read the base conditions—like humidity, temperature, water level, etc.—and see if they’re ideal for this plant. People could mint certificates of care for every fifteen-minute slot during the run of Art Dubai, but only if all the readings were in the green areas. So to be able to mint, you’d have to approach the plant, check the readings, maybe water it, or stop watering it.

DENNY To keep being able to issue speculative financial objects, the tree had to be in good health. Care was needed for speculation to continue.

KOLLING One could then argue that if you’ve already minted one of these certificates, you have an incentive to make sure that no other certificates are minted. This was solved by the care being done by the people on-site, the exhibiting institution—in this case, Fingerprints, who received a share of the raised money. So it’s a philanthropic model where the paid care worker turns into the DAO/art fair exhibitor, and the philanthropist is giving money to support the life of that tree through that sales mechanism.

DENNY In making my work, I’m more of a technology flaneur. I go through the existence of new emerging, interesting things that pique my curiosity and then try and make art about them, or art using them as a frame. I try to pull out what I find compelling about those companies—or environments or experiments or the people associated with things that I get attracted to—and make an artwork that brings other people to that fascination. I’m often in conversation with people in a few different camps, but I’m trying to bring that conversation back to the art context. Metaverse Landscapes is a good example: I was thinking about the rhymes between NFTs as speculative objects and paintings as asset containers for speculation. In the art world, painting is the motor and the container for a lot of value that gets created. How could I bring painting and NFTs together as a format? But I was also thinking about virtual land, from Decentraland onward, and the claims these worlds have made about extending territory, like in the colonial period, while often claiming to evade the costs of those colonial moments.

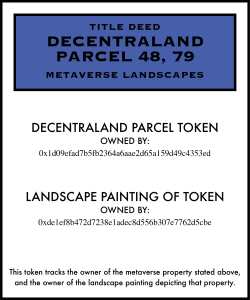

Metaverse projects sell NFTs that serve as title deeds for virtual land. These tokens were interesting to me from an aesthetic perspective as well, particularly Decentraland’s NFTs, because they have geometric depictions of land sliced up into rectilinear parcels. Digital space could be anything, but in this instance, they rhyme with the way physical land is divvied up. And the picture plane with rectilinear depiction resembles abstraction and modernist painting of the mid-twentieth century. So I thought making paintings that resonated with mid-century abstraction would be an interesting way to bridge all these interests. But rather than stopping there, I issued another NFT, which comes with each oil painting and tracks the original owner of the token that is depicted as well as the owner of the painting of that object. The painting is framed with a paper wallet, with a seed phrase underneath a scratch card. A couple of QR codes link to this new dynamic NFT that follows the wallets of the original metaverse token owner and the person who owns the painting.

One last layer that’s relevant is the continuity with other periods of painting. Landscape painting is connected to this colonial history that I’m a part of, that my family is a part of, because I’m from New Zealand and part of a settler lineage. In early colonial moments, when settlers were appropriating land, landscape painting played a role of familiarizing the settler community with the space and transporting legal imaginaries onto “new landscapes” owned by other people. The representation of land in places like New Zealand as they were being colonized paved the way for the naturalization of the idea that you could own such a place, that you could divide it up. So there’s a lot that comes together for me in the simple act of painting the token and issuing a property receipt for it, which resonates along all these frequencies.

SEIDLER I find it super interesting, especially the idea of how the division of land on a blank map has so much resonance with formalism of the twentieth century.

DENNY The claim to abstraction is in there as well, right? As a modernist painter, you’re not painting a window. The image is an object in itself. You’re taking aesthetics away from representation and putting it in a different format. Modernist abstraction is also really interesting to think about when you’re imposing another form of abstraction, such as property—where you’re saying that even though we live in a world of interconnected ecosystems, these parcels are separate and belong to different entities.

SEIDLER In the metaverse you don’t have any legal obligations. The code is the law because there is no other law. When we then go into real spaces, these issues get weirder and more cluttered.

KOLLING There are frictions between nation state law and code. But then there’s always the friction of historic, social, geographic contextualization—which is why we decided that the implementation of terra0’s first whitepaper is always set in Germany, in the historical context of this specific place.

Our work commissioned for the Carnegie International, A tree, a corporation, a person is a permanent public sculpture and our first work on US land, in Pittsburgh. We wanted to create the minimum viable version of the terra0 system, which would be a single tree as a public sculpture that would own itself, or be recognized as a legal entity with its own agency, in accordance with a very specific US law. We created a system where a piece of land is tied to the legal body of a lobbying campaign, which aims to fight for the personhood of the tree in front of a municipal court. Once this is achieved and a court rules that this tree should be recognized as a person, the 501(c)(4) lobbying entity will be transformed into an LLC, whereby the tree will become the sole owner and board of the company—a closed loop of ownership that takes the concept of personhood and property to its absurd conclusion.

DENNY That’s so interesting. There’s this dream of seceding in the blockchain space—the dream of having your own monetary system, your own territory, your own laws, etc. Where the rubber hits the road is where the tension really starts, right? We’re seeing that in the wider blockchain space with regulation and how suddenly these otherwise separate financial worlds are now meeting existing state apparatuses. But your piece may be one of the first footprints of this. What does self-sovereignty mean when it enters into a direct dialogue with the state?

KOLLING This reminds me of conversations we had as part of our research with web3/eco companies who make big claims about sovereignty. If you ask them how their plans can be implemented in the context of real law, they say they’ll move somewhere in the “Global South” where there’s no regulation.

DENNY Balaji Srinivasan’s book The Network State (2022)is relevant here. It’s often discussed in conversations about territory, digital territory, and extensions of capitalism and sovereignty into other forms. But the way Srinivasan’s theories often get put into practice is by assembling a group and finding a piece of land to buy. And of course the piece of land is always in Fiji or Costa Rica, which raises questions about neocolonialism. You don’t exit the problem of these power differentials simply by being associated with ideological projects. Not all technical projects are very advanced in terms of social considerations like these.

SEIDLER As terra0 we have a difficult relationship to The Network State. A lot of its ideas were around early in the community. There were projects like Bitnation, the voluntary governance system using Ethereum smart contracts founded in 2014, that tried all these things before. And they have failed because they have no notion of how history works, how pieces of land and communities are connected to certain local factors, like biodiversity and climate. All of this is lived history that has existed for a certain time. Thinking about it at the global level of pure abstraction misses important things.

DENNY The point where the abstract meets the real is a connector for our conversation. My paintings are both abstractions and representations at the same time. They’re also appropriations—they claim property, in that they copy Decentraland’s motifs. But they also issue their own new property on top of that. These are some of the things I’m trying to move to the adjacent allegorical space you guys are in with your test cases, where you enter dialogue with land, with nonhuman life, with legal structures. . .

SEIDLER And with state jurisdictions. The legal work we’re doing has been new and intense for us. We’rein meetings with nine lawyers, all from different backgrounds. It’s interesting as an art practice, but it can be difficult to manage.

DENNY Metaverse Landscapes comes out of my research for Mine, a four-year arc that started in another kind of distributed territory where financial speculation meets the art world—a private museum in Tasmania funded by one donor who made his money in the international gambling industry, by making algorithmic systems that beat existing gambling models. He puts part of his winnings into art philanthropy. I was thinking about the relationship between digital spaces of extraction and resource spaces of extraction, and trying to connect those things. Mines are almost entirely automated now, so Vitalik Buterin’s vision of DAOs as automated corporations also resonates with resource extraction methods currently in use. I was inspired by Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler’s work Anatomy of an AI System (2018),which maps the resources required for the existence of Amazon’s smart-home device Echo in order to bring physical and digital extractive models into closer proximity, to better see their similarities. The automated mine and the automated forest—there’s a dialogue with terra0, right?. This is also when I started to make artworks out of patents, another way of approaching property. I find a patent drawing and make an actual version of it. It’s not exactly making the product that is proposed by the patent—it’s making a sculpture of the claim to property. And that’s very resonant with Metaverse Landscapes as a gesture.

Do you feel that the relationships of care you’re coordinating with the blockchain stand in opposition to its extractive tendencies? I suppose the resolution comes in the incentive to own. That would be the blockchain’s traditional answer to that question: by redefining incentive structures, you can make good things happen rather than bad things.

SEIDLER Game theory is commonly used as a tool. You can nudge people through economic incentives. This works in some domains, but it’s not a universal solution. It’s a somewhat technocratic idea. I do think game theory has some practical applications, especially in defi, like liquidity pools or lending applications. But as soon as they come into contact with social systems or systems of care, it gets harder to quantify things. And this speaks to a general problem of quantification, which is relevant to terra0 but may be a separate conversation. In the iterations and experiments we noticed that our first whitepaper takes a conservative, classical approach to value and quantification.

KOLLING To address that we rewrote the terra0 whitepaper to realize it on a large scale as a land art project with Light Art Space in Berlin. The biggest change was a debate about the creation of value of the actual ecosystem. The whitepaper’s first version was very much aligned with the concept of proof of work. Money was made through the sale of licenses to cut down trees. It was an exploitative creation of value similar to conventional forestry. Our new project works with the financialization of an advocacy system or stewardship system, which we think is much more aligned with the current discourse about how we should relate to ecosystems. We should see ourselves entangled in the system. The progression syncs up with the naming of your exhibitions, “Proof of Work” in 2018 and “Proof of Stake” in 2021.

SEIDLER Proof of work is rooted in this notion of classical economy, with the idea that work has been done and is being paid for. And with staking systems, we are leaving behind the blockchain age of Fordism—

DENNY The Taylorist blockchain.

SEIDLER Yes, instead of the production line we’re in a more abstract financialized economy where capital can generate more capital just through abstraction processes that are no longer related to energy consumption.

DENNY This could sound quite Marxist, but the move from proof of work to proof of stake means ownership, rather than labor, produces value. That’s really interesting. I don’t know what that has to do with care, but it’s definitely a paradigm shift.

—Moderated by Brian Droitcour