Holographic Media

Media is no longer linear. Legacy outlets fade into noise, and communities have become filters through which all platforms are accessed.

The Bay Lights went dark in March. Leo Villareal’s generative light sculpture for the bridge connecting San Francisco to Oakland was installed in 2013, and every night for a decade its randomized patterns of white LEDs glittered in concert with the natural ripples of moonlight on water, softly illuminating the fog. But the hardware corroded over time. Villareal proposed improvements that would make the work more durable, but the city couldn’t pay the 11 million USD needed to undertake them, and private donors have not yet stepped up. John King, design critic for the San Francisco Chronicle, argued that this was for the best. He reminded his readers that the Bay Lights were originally intended to last for only two years; he felt the work overstayed its welcome. Public art, said King, is best when it’s temporary, when it creates a festive atmosphere for a short time, then recedes into fond memories.

I wouldn’t agree with King’s assessment that the Bay Lights got stale. While there were constants in their parameters, they were always changing—much like the conditions of the climate and weather that Villareal’s work was responding to. But I am intrigued by his opinions on public art’s role in urban design. In recent years activists around the world have removed statues of colonizers and slavers from public space—sometimes through bureaucratic channels, sometimes by force—drawing attention to the contested nature of the urban realm and how monuments stake out values that many citizens find alien. Even a century ago monuments felt archaic, a relic of nineteenth-century nation-building; they have been displaced by the more flexible genre of public art. The historian Lewis Mumford declared the monument dead in 1937, and in the ensuing decades artists too numerous to list here have experimented with nonmonumental forms: soft and flexible, wheatpasted and mobile, ephemeral and disposable. Recent years have brought a proliferation of digital nonmonuments. While the Bay Lights were fused to permanent infrastructure, other works of digital art can inhabit public space temporarily and unobtrusively, drawing attention for a fixed period and leaving without a trace.

One notable recent example is Refik Anadol’s Living Architecture: Casa Batlló (2022), a digital animation first projected for one night onto a Barcelona building with a façade designed by Antoni Gaudí. Anadol enhanced Gaudi’s asymmetrical bulges and curves with his signature fractal animations, where cubic shapes spill into fluid ones, as if visualizing the crystallization of data into form and vice versa. Anadol often takes sprawling topics as the subject of his work—cities, museum collections, nature, technology—which arguably suits the capacity of his AI tools to process vast data sets. But Living Architecture benefits from its tighter focus on a single architect and a single building, which is brought alive in a dialogue across time to be seen in ways it could not before. The project debuted last year and its success led to repeat presentations, drawing massive crowds to Passeig de Gràcia. It also lives on in derivative animations that Anadol has installed in other public spaces, including New York’s Rockefeller Center.

Artists have long experimented with nonmonumental forms: soft and flexible, wheatpasted and mobile, ephemeral and disposable.

Projection mapping, a method of adapting digital media to specific surfaces unlike the standard screen, was essential to Living Architecture,and it’s also employed by Art on the Mart, an organization that displays video and animation works on the façade of the Merchandise Mart, an Art Deco behemoth built on Chicago’s riverfront as a trading post in the 1930s. The imposing structure, spanning two city blocks, poses challenges for display not just because of its scale but because of its texture; commissioned artists must contend with how their work will pass over the dozens of recessed windows. This factors into the concerns present in any instance of projection mapping: how color, brightness, and speed of motion will interface with the environment. Charles Atlas, a seasoned veteran of projection, found a brilliant solution in The Geometry of Thought (2019). After appearing around the margins of the building, animated numbers exploded in bursts like fireworks and flitted in swarms, playing hide and seek as they darted in and around the façade’s grids. For her commission Love Letters (2022), Yuge Zhou smartly worked with big blocks of primary color. A dancer in red moved through a field of blue while another dressed in blue danced against red; the footage of the human performers shrank and grew to create a sense of depth, and to enhance subtleties of movement that might otherwise be lost due to scale. As the piece progressed the colors blended and merged in dazzling patterns of purple.

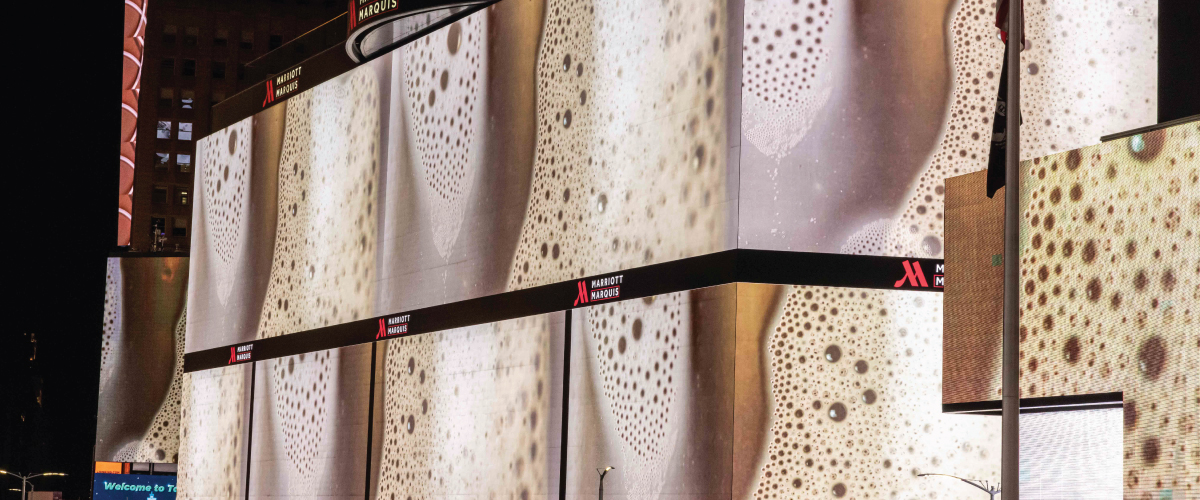

Art on the Mart’s projections are view in the evenings from spring to fall. The riverwalk is a popular promenade, so people strolling at night are likely to encounter it by chance. Operating since 2018, the program is ever-changing, but a regular fixture. The Midnight Moment by Times Square Arts is another public art initiative following a similar model (and also administered by a nonprofit in collaboration with commercial real estate). Every night, for three minutes beginning at 11:57pm, nearly one hundred digital billboards in New York’s Times Square show video art. It’s the only time when they are in sync. The most recent commission, Ilana Harris-Babou’s Liquid Gold (2023), showed closeups of breast milk and baby formula, bubbling and frothing. For her 2021 commission Flesh Wall,Sondra Perry likewise united the screens with a common moving texture, in this case a digital rendering of glistening, undulating muscle and fat.

If the classical monument structures the flow of movement through public space, the digital nonmonument mimics and augments this flow.

Times Square’s digital billboards come in many shapes and sizes, so artists need to think about how their work might adapt to the available formats, offering different versions to suit horizontally and vertically oriented screens. There are three extremely tall screens, and artists often opt to tile their work in a column to fill it—though some, including Nancy Baker Cahill and Krista Kim, have created site-specific videos to take full advantage of the dramatic upward sweep. In 2020, the Brooklyn collective Optical Animal updated their 2016 work Projection Napping into a 90-channel installation of videos of sleeping bodies, so that each screen appeared to have a napper nestled in it. Few head to Times Square to see the Midnight Moment; the site is a destination in itself, but the video is the sort of unexpected, dynamic experience that a visitor might hope to encounter there. Whether artists blanket the billboards with a unified visual texture or highlight their differences with bespoke imagery, the effect of so many screens operating in concert is striking. Media theorist Giuliana Bruno has argued that the essence of cinema is public intimacy—that moving images elicit emotional responses experienced together in the architecture of a theater or a museum. The dozens of channels of the Midnight Moment model how that kind of attention, fragmented and shared at once, changes in the less controlled conditions of the city streets.

For the last few years, Marcos Lutyens has been developing a Covid memorial that can exist in multiple locations across the US, and can grow and evolve over time as more people contribute images and stories of loved ones lost to the disease (and as deaths continue to accumulate). His solution is to use augmented reality: at designated sites, visitors can use their phones to access the memorial, with physical installations serving as anchors for AR apps to position the visuals. A version of a National Covid Memorial debuted in Los Angeles in October, sponsored by the company behind Snapchat. Portraits of the dead appear in a moving helix, spiraling heavenward; viewers can select images to learn about the people they represent. (A World Covid Memorial, supported by the World Health Organization, will be hosted by the All India Institute of Medical Sciences in New Delhi in September, with subsequent presentations planned for other cities. In this iteration of Lutyens’s project, the individual memorials will appear initially as flowers whose petals open to reveal images and stories, building on associations of flowers with mourning.) Like the virus itself, the Covid memorial exists as an invisible, constant presence, only coming into focus when attention is paid to it.

While initiatives like Art on the Mart and Midnight Moment make use of commercial infrastructure in the built environment to find space for art to inhabit, the Covid memorials take people’s phones—already personal and intimate—as the channel for digital media. There is a poignancy to the hidden nature of the dormant monument and the distribution of the memorial across personal devices—and to the fact that it exists thanks to private initiatives, supported in part through NFT crowdfunding. The form conceived by Lutyens is strikingly apt, but it underscores the American state’s unwillingness to erect a permanent, solid memorial that would highlight its failures.

If the classical monument structures the flow of movement through public space, the digital nonmonument mimics and augments this flow, adding light, color, and other sensory stimuli to an environment already rich in them. Sometimes it catches the attention of a slowing passersby, sometimes it becomes yet another overlooked element of a busy background. In this sense the digital nonmonument is like digital art online. When users come across art in their feeds, they may scroll past, they may stop to contemplate, they may even open a new tab to explore further. Art online coexists with the rhythms of online social activity. The nonmonument may be more adequate than a museum display as a translation of digital art off (or, in the case of AR, partly off) the screens of personal devices. The museum strips away extraneous contexts, but the nonmonument coexists with them, reflecting how digital media is woven into the fabric of life, bound to material infrastructures but flowing through them, like people, and can yield surprising experiences, to share and to savor alone.

Brian Droitcour is Outland’s editor-in-chief.