Economic Provenance and the Audit Problem

How can expertise from time-based media art conservation help appraisers vet NFTs?

What makes someone want to be in the metaverse? Second Life came up with the most elegant answer to that question—a sandbox to play with identity via avatars among others who share that interest, which it has provided to a small but dedicated userbase for two decades. Newer virtual spaces have tried to innovate and appeal to broader audiences, but so far nothing has stuck. Decentraland, a blockchain-based metaverse, was launched as a virtual land grab, and the plots sold to speculators are mostly still fallow. Meta and Microsoft’s early versions of their respective metaverses were mocked for being little more than cartoon meeting rooms. Meta briefly hosted a residency for artists to design virtual worlds, in the tradition of enlisting art as corporate R&D, but slashed that initiative during the mass tech industry layoffs early this year. HTC, the maker of VR headsets, is also building its own metaverse—the Viverse—and, through its art and technology program Vive Arts, has supported the CripTech Metaverse Lab, an incubator organized by Leonardo and Gray Area to involve disabled artists and designers in the development of virtual worlds. The results were presented in San Francisco last month at the Gray Area Festival, called “Plural Prototypes,” and as the title suggests they indeed offered strikingly different visions for the potentials of virtual space.

Virtual worlds are often designed with the same assumptions of ability that structure physical spaces.

It has become a truism that virtual reality can be a boon for the disabled because it transcends the physical limitations of meatspace. And yet 3D social worlds are often designed with the same assumptions of ability that structure physical spaces, and carry the same biases. The CripTech Metaverse Lab operates from the proposition that inviting artists embedded in particular communities is the best way to respond to those communities’ needs, resulting in the creation of virtual spaces that people will actually want to use. Melissa Malzkuhn and Indira Allegra, the artists selected to participate in the incubator, were connected with engineers and 3D designers who could help them realize their ideas, while pushing the technological limits of the Viverse and indicating directions for future development.

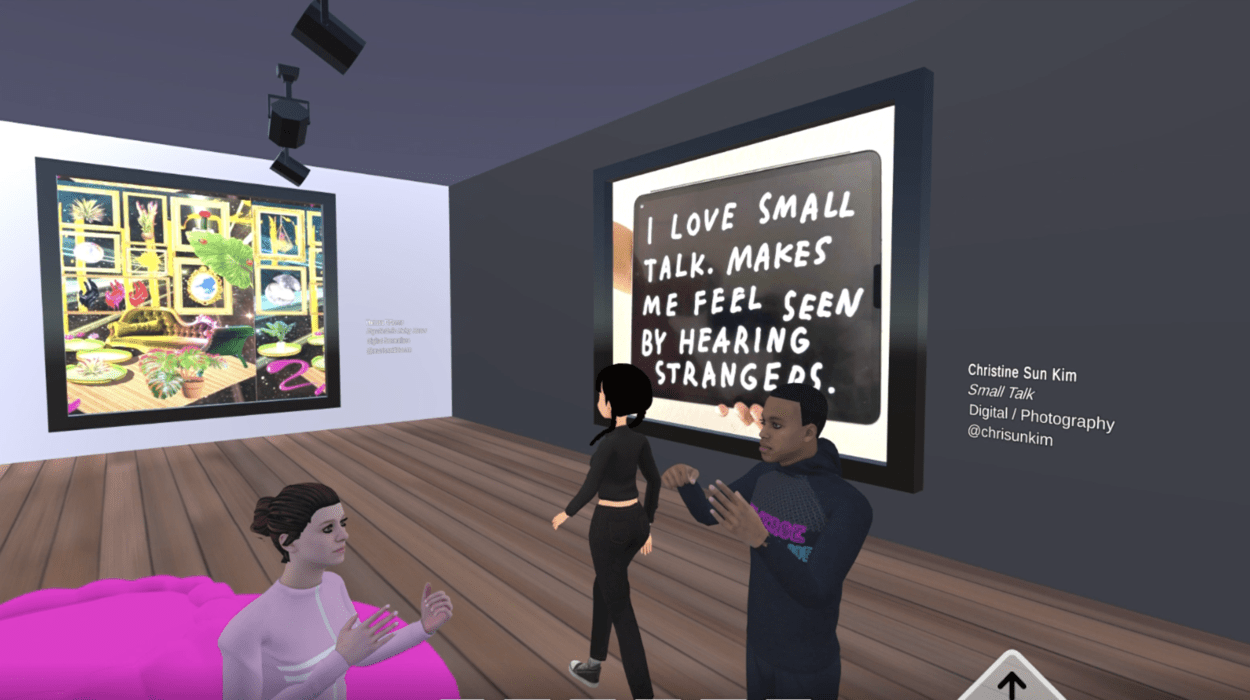

Malzkuhn built a virtual Deaf Club, based on the kinds of spaces she often visited with her family growing up but have been crowded out by gentrification. “The most important thing we need is space,” the Deaf activist said in her presentation at Gray Area. “And that’s what the metaverse has provided.” Her three-story building, with a façade based on that of a former Deaf club not far from Gray Area, differs little at first glance from other spaces in the metaverse, with stairs and rooms you jump through via Viverse’s point-and-click navigation. Malzkuhn wanted to emphasize the role of Deaf clubs as cultural spaces, so she built a stage for performances and hung the walls with works by twenty Deaf artists. One striking divergence from other virtual worlds is the inclusion of mannequins—avatars frozen mid-sentence, their hands raised and forming signs. What Malzkuhn really wanted for her world was avatars who can fluently sign, moving their digital hands with all the dexterity and expressivity that real ones are capable of. The Deaf communicate not just with signs but also with how they sign, but the current technology for 3D worlds can’t yet accommodate that. Malzkuhn’s mannequins are placeholders for a future where more fluent, idiomatic expression is possible. Her critique indicates a universal problem of the metaverse—the mostly static appearance of avatars gives 3D social spaces little advantage over the text-and-image-based social platforms we have now.

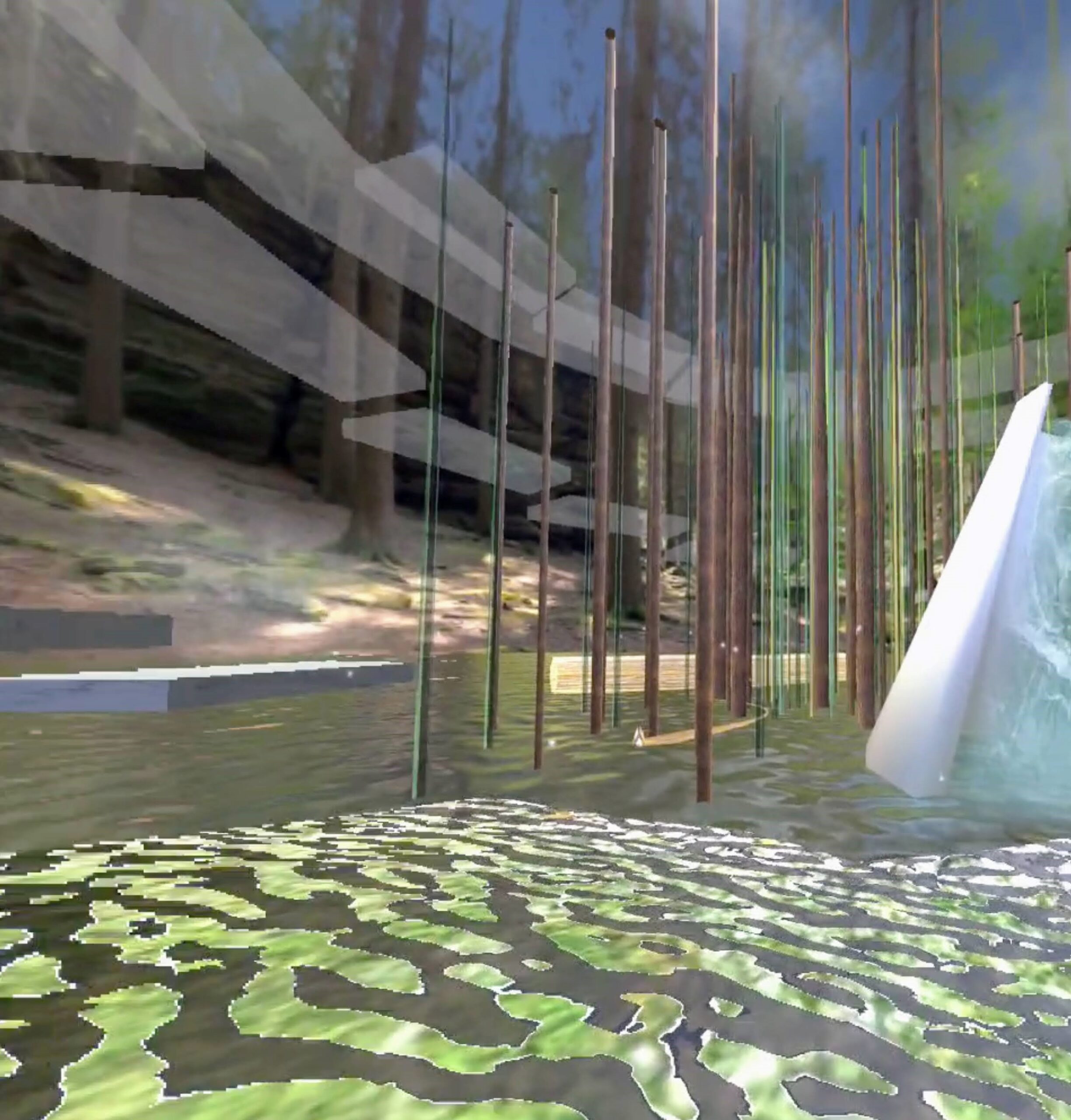

While Malzukhn’s Deaf Club put the focus on external stimuli and interpersonal communication, Indira Allegra designed their virtual space Texere to be conducive to solitary contemplation and introspection. Allegra, whose art is linked to their therapeutic work with survivors of trauma and sickness, created a space for mourning. You teleport to a pool in a glade; there is no representation of a path that would suggest connections to other spaces. You don’t have a digital body in Texere, instead appearing as a drop of water, as if you belong to the pool but have temporarily risen from it. A spiral staircase of floating white platforms rises over the pool, encircling a cluster of columns that rise toward vanishing points in the sky. Shimmering shapes weave around the columns just above the pool’s surface, leaving momentary tracks in the water. Allegra offered a few possibilities for expression: you can make emojis burst in a cloud from your avatar-drop, or draw in 3D to leave squiggly, colorful messages and images that future visitors to Texere will be able to see. Each element of Texere’s design participates in a dialogue of stillness and movement, of permanence and ephemerality, that encourages reflection on loss and change.

A third prototype was developed was in collaboration with New Art City, the browser-based platform for virtual exhibitions. New Art City launched in 2020 so that art students at San José State University could have a graduation exhibition despite gallery closures due to Covid lockdowns, and grew into a platform used by many artists and institutions. Touch, Nat Decker’s project for New Art City, is an abstract space of extruded, mottled forms, floating in a white void. There’s no avatar here at all. You have to imagine yourself bodiless, as a gaze that selects points to explore through its direction. This is New Art City’s first foray into VR. Don Hanson, the platform’s founder, advocates browser-based XR for reasons of accessibility and openness, as the technology can be used without proprietary headgear. This project is an experiment in portability, developing a world that can be visited either through a headset or a browser.

There’s no one answer to the question of what makes people want to use the metaverse, and so the metaverse will have to offer many.

Decker’s piece, like Allegra’s, is an art installation rather than a community space, with its own expression of agency that doesn’t translate the body into virtual metaphors. The implicit message of “Plural Prototypes” is that the metaverse to come won’t be a mass platform where everything conforms to a singular logic but rather it can offer multiple types of spaces and experiences. At a time when the big platforms of Web 2.0 have lost the trust and enthusiasm of their users, it’s easier to imagine the metaverse as a “dark forest,” a version of the internet comprised of many private or semi-private spaces, as described by Caroline Busta and Lil Internet in their essay “Holographic Media.” The prototypes that came out of the CripTech Metaverse Lab affirm this vision. There’s no one answer to the question of what makes people want to use the metaverse, and so the metaverse will have to offer many.

Brian Droitcour is Outland’s editor-in-chief.