2022 in Review: ARTISTS on NFTs

We asked artists working with NFTs how their environment has changed over the past twelve months

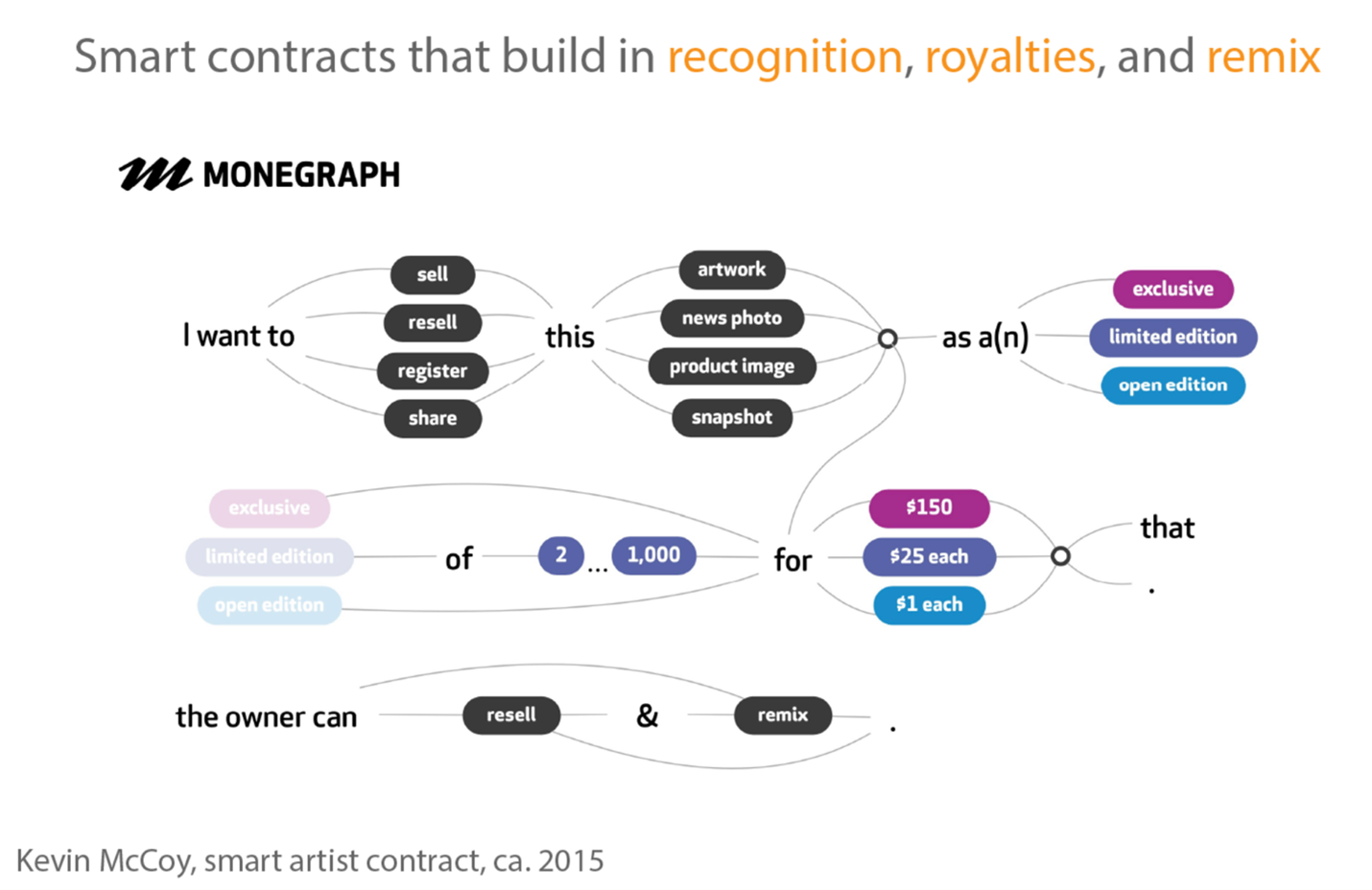

In May 2014, Kevin McCoy and Anil Dash presented their business concept of ”monegraphs,“ short for monetized graphics, at the New Museum during Rhizome’s annual Seven on Seven conference, which pairs artists with technologists. McCoy and Dash’s monegraphs, tokenized certificates of authenticity (COA) combined with purchasing agreements, were proto-NFTs. As early as October 2013, McCoy posted to a message board about his interest “in developing a system where a contractual ownership token or message can be embedded with a blockchain transaction.” After Seven on Seven, he launched Monegraph as a company. Around the same time, the German start-up Ascribe developed a mechanism for securing digital art on the blockchain, releasing a protocol, backend, and app in 2014. Despite gaining some traction, Monegraph and Ascribe ultimately folded. Neither the technology nor the popular understanding of the blockchain had been sufficiently developed at the time for these companies’ tools to commodify its potential.

The early efforts toward authenticating art on the blockchain saw the potential of NFTs. They understood the crypto token’s functionality as an advanced digital version of a certificate of authenticity, combined with more evolved options for setting permissions to sell and collect royalties. Monegraph focused on digital art in order to support artists working in a medium that, despite some acquisitions by institutions and collectors, was still struggling to find its place in the art market. Surveying today’s NFT landscape, one could speculate that the crypto entrepreneurs who built today’s NFT marketplaces were less motivated by a desire to support digital artists than they were by the ease of developing markets for digital images and collectibles whose creators wanted adequate financial compensation and were therefore eager to join. The potential of the crypto token as an advanced, expanded COA is obscured by its use as a sales mechanism. To ensure the long-term success of NFTs, this potential must be realized by offering more utility to artists, museums, and serious collectors.

The potential of the crypto token as an advanced, expanded COA is obscured by its use as a sales mechanism.

The term “NFT art,” commonly used to delineate digital fine art from memes and collectibles, creates the impression that the art labeled as such uses a new medium and thereby obscures the fact that NFTs are not intrinsically linked to digital art. (This is only true in cases where artist use the blockchain and the token as their medium, which account for a very small portion of so-called NFT art.) NFTs reside on a blockchain while the art they authenticate usually does not. As a combination of COA and purchasing agreement, the smart contract contains a link to a centralized server with metadata that in turn links to the actual artwork, often stored on the IPFS (InterPlanetary File System), a peer-to-peer protocol for setting up networks.

Since it is not intrinsically connected to the artwork, an NFT can be minted for any type of art, even irreproducible, non-digital forms like painting and installation. Most forms of digital art—from installations and software art to virtual reality and even most net art—are in fact not easily reproducible. Digital artworks did not need NFTs to secure their authentication. They were bought by collectors and institutions as unique or editioned works for decades, authenticated by paper certificates. Only some kinds of digital art—namely, easily reproducible digital images and short movie clips that “live” and circulate on the Internet—benefit from the public digital record of ownership provided by NFTs.

Most of what is known as digital art in the fine art world is much more complex than a jpeg or animated gif. Artists and gallerists entering the NFT landscape now often mint NFTs for stills or brief clips from complex and interactive digital artworks to adapt them to the market’s constraints. Since the NFT market is so hot, the works themselves can cost less than their excerpted versions sold as NFTs. To museums or devoted collectors of digital art, the NFT is consequently much less interesting than the piece from which it derives.

The monetary value of art has always been built around scarcity and authenticity, and the scarcity for reproducible media, such as photography and video, has been ensured through the process of editioning. Artists like Andy Warhol even managed to turn replicas of mass-produced items, such as Brillo Boxes, into highly valuable artworks. For galleries and dealers, the COA is crucial for setting monetary value; for museums, which are not in the selling business, its value is in provenance and research. NFTs introduce a subtle perceptional shift in the designation of value. Traditionally, collectors and institutions acquire an artwork accompanied by a COA. In the case of NFTs they purchase the certificate that encodes the ownership and, usually, the location of the artwork. People talk about “buying” NFTs rather than acquiring a specific artwork through an NFT. The sales mechanism itself has been commodified: a capitalist milestone. Artist Tino Sehgal has been one of the ultimate disruptors of these market mechanisms, famously selling his performances for five-figure sums by oral contract—without exchanging any paper, be it bill of sale or COA.

The impact of NFT art has been both positive and problematic. On the upside, a segment of the crypto world has discovered the breadth of digital art’s forms and their history and started collecting it. On the downside, the label “NFT art” conflates work that uses the blockchain as a medium with the sales mechanism of selling generic digital images via tokenized COAs. Some artists have taken up the generative potential of the blockchain to comment on this commodification of the sales mechanism. Artist Jonas Lund’s MVP (Most Valuable Painting), 2022, is a participatory artwork consisting of 512 digital images subject to processes of transformation. When an MVP is minted and sold, its properties determine the evolution of the remaining ones: a fitness algorithm tracks each MVP’s engagement on social media and “optimizes” the composition of subsequent images to generate maximum attention. The last image sold therefore captures all the aesthetic value assigned to it by viewer and collector preferences over the course of the project.

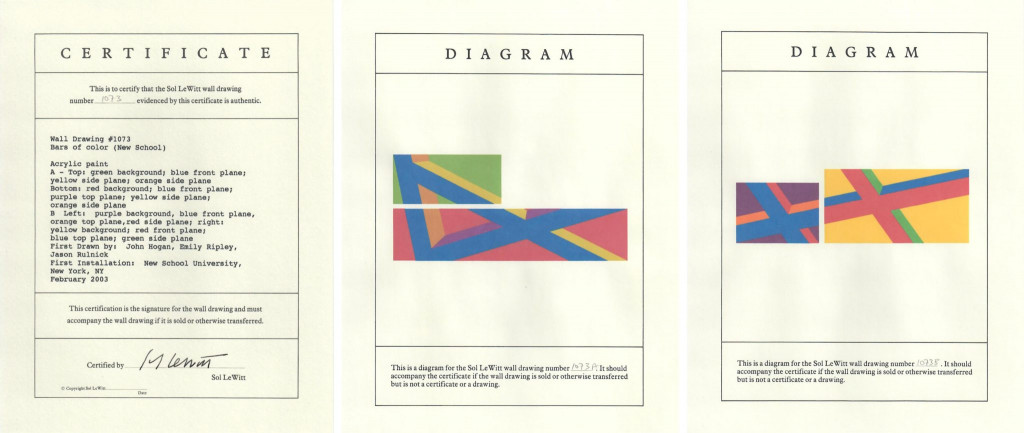

The current focus on the NFT as sales mechanism distracts from the NFT’s potential as an expanded certificate of authenticity. By combining a record of ownership and provenance with flexible copyright details, sales and preservation strategies, the NFT could become a more sophisticated authentication tool. A paper COA usually exists separately from the purchasing agreement and information that institutions and arts organizations collect for the future presentation and preservation of artworks. A rare exception is the conceptual work of Sol LeWitt, whose wall drawings include the work itself—the instructions for executing it—on its COA. Of any analog artwork, LeWitt’s COAs come closest to an NFT that mints the code of work on the blockchain, such as Rafaël Rozendaal’s NFTs of his generative abstractions.

While NFTs indeed hold great promise for a much-needed upgrade of the rudimentary COA, the reality is still far from the potential. The majority of NFTs are minted for buyers of newly created images or animated clips, starting provenance at zero, rather than for preexisting, older works whose past ownership could be encoded in all its detail. Moreover, the in-depth information pertaining to an artwork that is gathered by museums in the acquisition process might not be easily embedded in smart contracts or stored on-chain. For digital artwork in all its forms—net art, software art, installations, virtual and augmented reality—this information comprises the history of the work and its creation; materials, techniques, and expertise utilized; technical specifications; installation instructions; and preservation-related information ranging from file formats and their structure, organization, significance, and functionality to electrical wiring, and even wall color and finish. All this information would likely be stored off-chain, which requires a repository that ideally supersedes the functionality of a museum server.

The sales mechanism itself has been commodified: a capitalist milestone.

Left Gallery (2015–2022), cofounded by artist Harm van den Dorpel, developed more sophisticated smart contracts with expanded language pointing to the publicly available display copy of the work (residing on the IPFS) and a complete archival package for the collector, containing recommendations for preservation and information on the artist’s intent. Left Gallery’s contract also creates a digital twin of the metadata file on the artist’s server, linking to the smart contract for verification, so that the artist can certify their own work and retain sovereignty over their identity. Some artists are addressing the inherent shortcomings of smart contracts. Nancy Baker Cahill’s “Contract Killers” (2021) is a series of site-specific augmented reality works that show dissolving handshakes. By minting them as NFTs she positions the smart contract among other kinds of contracts—social, judicial, financial—and highlights the instability of all of them. Baker Cahill has been working with lawyer Sarah Odenkirk to build an off-chain contract for digital art sales with stronger protections for owners and creators.

The transparency of the ownership record on the blockchain is yet another area where reality doesn’t yet live up to the promise. While provenance, the history of a work that includes changes of ownership, would be transparent to the public, many NFTs are bought via anonymous wallets that obscure the owner’s identity. Not every buyer wants transparency, and anonymity has long been of value to high-end collectors who want to keep their holdings private. At the same time, no system can be made completely secure and anonymity can be cracked.

The NFT space is still nascent and has many systemic issues to address, from environmentally sustainable models for minting and marketplaces to a range of security issues. But it is realizing the potential of NFTs for functioning as expanded certificates of authenticity for art at large that will be a key factor in building ties to the art market.

Christiane Paul is adjunct curator of digital art at the Whitney Museum of American Art and a professor of media studies at the New School in New York.