Arkive

A DAO building a museum-quality collection lets its nearly 1,000-strong membership participate in decisions usually made by exclusive acquisitions committees.

Contrary to the name, the Bavarian State Paintings Collections in Munich run the gamut of fine art—from old master paintings to video and digital work. The holdings from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries are housed (along with the state collections of architecture, design, and graphic arts) in the Pinakothek der Moderne, which presents a public program of exhibitions drawing on loans alongside collection works. “Glitch: The Art of Interference,” an ambitious survey featuring more than fifty artists from around the world, opens on December 1. How do you tell the story of glitch art, which so far has largely played out on the internet, in a museum? Franziska Kunze, chief curator of photography and time-based media for the Bavarian State Painting Collections, spoke to Outland about the development of an exhibition that spans time periods and media—and invites audiences to think about glitch not as a specifically digital art form but instead as a conceptual strategy with a diversity of both means and ends.

I started working at the Pinakothek der Moderne in August 2020. When I had my job interview, I was asked to pitch an exhibition. My proposal was essentially what became “Glitch: The Art of Interference.” The initial idea came from my PhD dissertation, in which I explored how materiality in art is brought to the foreground through moments of failure in the medium. I focused on analog photography, although in the final chapter I looked at more contemporary examples within digital art. Quite a few of the artists from my dissertation have ended up in the exhibition.

One of the first works you encounter within the introductory chapter “Switch to the Glitch,” Peter Weibel’s The Endless Sandwich (1970/72), encapsulates the argument I’m trying to make in the show. It’s a video of a mise-en-abyme: a man sitting in front of a monitor that shows an image of the same man in front of the same monitor and so on. In the smallest image, the monitor starts to glitch and the man gets up to fix it—an action that cascades through the images. When something isn’t working with technology, that’s what happens: we stop being passive consumers and get up and act.

This is not a traditional “glitch art” exhibition, which you can tell from the timespan of the show. The oldest piece is Ma Dernière Photographie (1929) by Man Ray. It’s an empty black surface made by exposing silver gelatin paper to light. Normally when people think of glitch art they think of video or computer-based work. But photography came into being as a glitch—what we consider now to be a photograph, a clear window on the world, took practitioners a long time to achieve. There were so many “failures” along the way. At a certain point, artists started to become interested in these failures, and even trigger them intentionally, using them as a way to explore the materiality of photography, video, digital imagery, and even sound.

The first proper chapter of the exhibition, “Born to Glitch,” shows a range of analog examples of this kind of work from the twentieth century—from Man Ray onward—alongside vitrines containing photographic magazines and manuals from the time. It’s important to note that most of these artists who decided to work in this way were fully aware that they would not be very successful on the art market. It’s always been hard for photography to compete with other media, and for this kind of photography it was even harder. These artists were, actually, quite brave—firstly to break the rules and then also to do something that would probably not sell.

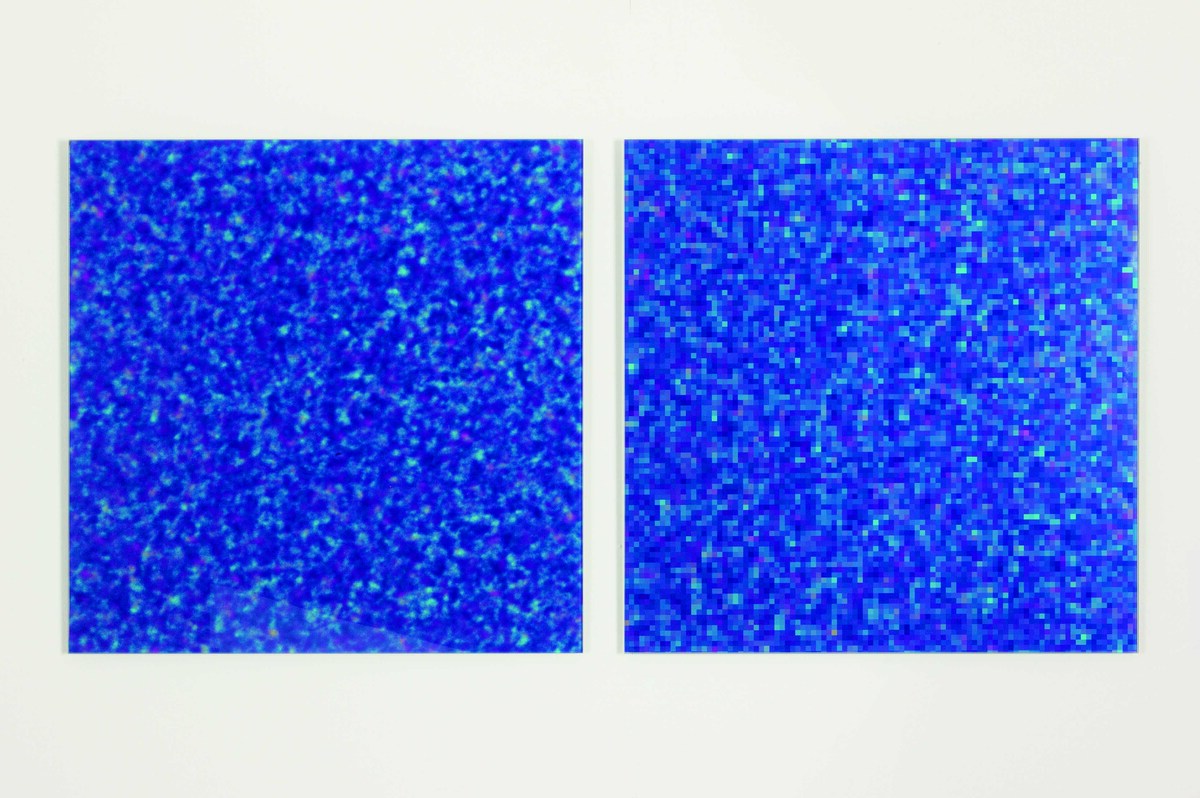

“Loss of Control,” the second chapter, gathers artworks in which artists have systematically charted different possible glitch effects in their respective mediums—exploring how by “losing control” over their medium they can gain insight and understanding. For instance, Bleu du ciel (2001/04) by Inge Dick pairs an analog photograph and a digital image of the sky, both in extreme close-up so you can contrast the grain of the photographic print and the pixels of the digital image. Rosa Menkman’s landmark glitch artwork A Vernacular of File Formats (2010) is also in this section.

Next, in “Twisted Worlds,” we explore how artists are employing these glitch effects—again, both with analog and digital media—and pushing them to their extremes. This section contains the newest piece in the show, by Fabian Hesse and Mitra Wakil. The work takes as its starting point their public sculpture Westpark Clouds, which was installed in Munich in 2016. It’s a group portrait of local people melted together and glitched using 3D modeling software. For this exhibition, they’ve scanned the sculpture so you can view it on your phone in AR—in the exhibition space or at home, or wherever you are. This adds another layer of glitch, because when other people walk in front of your phone, they appear to move through the sculpture, becoming part of the piece.

Then we come to “Critical Disruptions.” This last chapter is about artists using glitches as a means of critique. They’re exploring issues like ethnic background, class, and religion as well as sexual orientation and gender. They are also addressing global catastrophes and wars. For instance, there’s a work by Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, who went to Afghanistan in June 2008—the deadliest month of the war there—with the British army. They brought a roll of photographic paper and, instead of taking regular photographs, they would expose a six-meter-long section of the roll to the sun and the dust for twenty seconds to mark certain events. Often, with these difficult subjects, people’s experiences can’t be depicted with a “perfect” photograph or image. Flaws become a visual tool to comment on what is happening in the world.

It was difficult to make the selection of works for the exhibition—I had to kill so many darlings. Most of the pieces are loans but by chance each section features one work from our collections. Some of those works were acquired during the process of organizing the exhibition. Christian Doeller’s 730331879 (2010/23) is a print of a long-exposure photograph taken with the camera’s lens cap on: a mostly black image scattered with “hot pixels” that are the result of disturbances in the camera’s sensor.

Then there’s Sondra Perry’s Double Quadruple Etcetera Etcetera I & II (2012). In this two-channel video the artist uses technology to explore what it means to be Black in a white society—to be invisible and hypervisible at the same time. The video of two Black dancers in a white room is processed using the content-aware function in Photoshop in order to overwrite the dancers with their background. Except the software doesn’t do its job properly, and at times the moving body parts of the dancers are visible, fighting against the process of being deleted.

Also drawn from our collections are some works by well-known artists, which mess with photographic processes but have never been considered from the perspective of glitch before. There’s a 1930s still life by Florence Henri, which is part of the collection of the Ann and Jürgen Wilde Foundation within Munich’s state collections; a 1980s piece from Sigmar Polke’s Desastres und andere bare Wunder (Disasters and Other Sheer Miracles) series; and a Wolfgang Tillmans, who was pretty surprised to be included with his 2004 work Freischwimmer 52! I’m curious to find out what people are going to think about this new context for these works.

—As told to Gabrielle Schwarz.