The gm, the Bad, and the Ugly

In this week's news: The questionable funding of celebrity NFT projects, the $MOCA hack, Brantly Millegan's removal from ENS, and the advent of gmDAO.

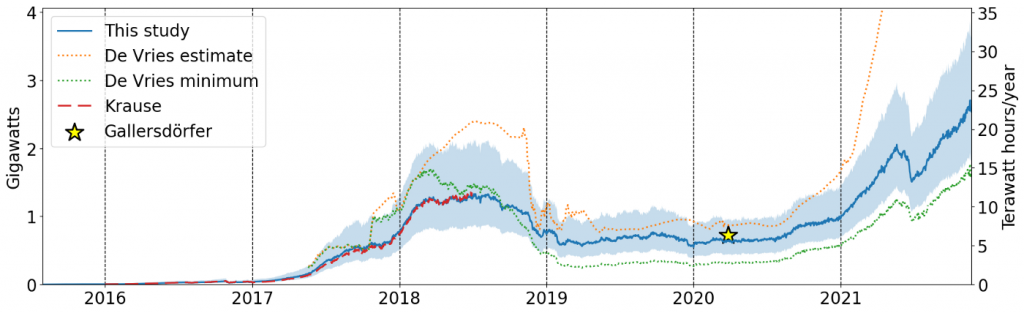

NFTs seem to be a magnet for debate. Do they represent a radical break from the traditional art world—or do they actually reflect the same systems of value that have always governed cultural production? What of their politics? Are they fascist? Neoliberal? Communitarian? How should we deal with their environmental impact? Until this September, when the long-awaited “Merge” finally saw the Ethereum blockchain move from a proof-of-work protocol to proof-of-stake, artists were regularly condemned for minting works due to the energy costs—but in the grander scheme was this really such a fair accusation? And can anyone even agree what they are—artistic medium, certificate of authenticity, sales mechanism, financial instrument, all of the above? Looking back at the articles published on Outland over the past year—from pieces of commentary and criticism to artist conversations—gives a sense of the issues that have fired people up. While there is a clear consensus on some topics, at least among the artists and critics in this magazine’s orbit, at other times perspectives have diverged.

Essays on artists such as Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst, and Takashi Marukami have served as an opportunity for writers to work through the relationship between web3 and the mainstream art world. Sean Kennedy, discussing Koons’s NFT-and-sculpture project with Pace Verso, wrote: “What has continually been the case in web3 is the revelation of the more profane aspects of market society that would otherwise be opaque.” But he also argued that “Neither Pace’s nor Koons’s bold entrance into NFTs needs to be celebrated. To many artists and art-lovers, the appeal of web3 is to work in the arts in a way that escapes the domineering and exploitative practices of these insular mega-galleries.” Jonah Goldman Kay, in a review of Hirst’s The Currency (2021), suggested that the engagement of blue-chip artists and galleries with NFTs has been superficial at best: “Hirst may be well-placed to take advantage of web3’s normalization of direct-to-consumer art, but he’s apathetic to the concept of digital ownership. […] [H]e replicates a tired formula used by artists and museums who see NFTs as a way to wring more money out of preexisting works.” On a virtual Murakami show at Gagosian, meanwhile, Simon Wu was left feeling disembodied, “weak and unwieldy.” His essay suggested that the white cube—and the kind of art usually displayed there—might not translate so well to the metaverse, after all.

Through the lens of individual projects, contributors also considered the political underpinnings of NFTs. Mad Pinney addressed the elephant (or rather, ape) in the room—accusations of racist propaganda in Bored Ape Yacht Club PFP imagery—to pose a question with broader implications: “Could the speed of the NFT market—which often comes at the expense of reflection on artistic intent and sociopolitical context—allow fascist aesthetics to circulate unencumbered in a time when far-right extremism is on the rise globally?” Charlie Markbreiter, in an essay on the artist Timur Si-Qin, took a different tack, arguing that the NFT market, with its emphasis on individual economic freedoms, is a fundamentally “neoliberal solution to austere times.” Looking beyond tokenized art and more broadly at the crypto-trading market, Alex Iadarola suggested that “the mainstreaming of crypto” reflects the encroachment of speculation into all areas of the economy. “Financialization is so ingrained that it’s difficult to name a thing that isn’t somehow shaped by speculation,” he wrote.

But are there more communitarian possibilities for art on the blockchain? For Wade Wallerstein, LaTurbo Avedon’s online Materia project was an example of how NFTs can “enable a plurality of community-led worlds.” “The metaverse,” wrote Wallerstein, “is inherently DIY, and should never be limited to corporate manifestations.” In a conversation around the theme of “infrastructural critique,” a Palestinian collective entitled The Question of Funding put forward their proposal for a new cryptocurrency, Dayra, that would be geared not towards financialization but towards the sharing of knowledge and skills. As the collective member Yazan Khalili explained: “With Dayra we’ve been trying to push against the speculative economy of crypto. If crypto is a trustless structure, how do we then bring it within trust structures, not to create speculative financial instruments, but for actual social uses? We are trying to move away from digital assets. The idea of Dayra is about minting the act of sharing.”

The high carbon cost of blockchain technology, especially before Ethereum moved to proof-of-stake, was identified by Jeffrey Alan Scudder as one of the key reputational obstacles holding back widespread adoption of NFTs. Essays by Charlotte Kent on Leo Villareal, Kyle McDonald, and John Gerrard lauded those artists for acknowledging the environmental impact of the infrastructure on which their work was built. In reference to McDonald’s Amends (2022) project, Kent argued that “[b]y participating in NFT marketplaces to enact his critique, McDonald recognizes his own culpability, rather than taking a moral high ground to blame and shame.” But Kent also suggested that the reputation of NFT artists may have been unfairly tarnished by this issue. What about the “crypto traders who wield significantly greater transactional influence” on blockchains? And the art world in general? In her essay on Gerrard’s Petro National (2022), Kent wrote: “The advent of NFTs […] has deferred criticism of the art market’s dependency on fairs and the ecological costs of related shipping and flights.” Since the Merge, this debate has simmered down. Still, the climate crisis hasn’t gone anywhere. In an essay on Marcelo Soria-Rodríguez and Andreas Rau’s Toccata (2022), A.V. Marraccini captured the prevailing sense of apocalyptic anxiety: “Futurity itself seemed to be in the balance; if the world ended soon enough, the idea of blockchain posterity wasn’t really viable anyway.”

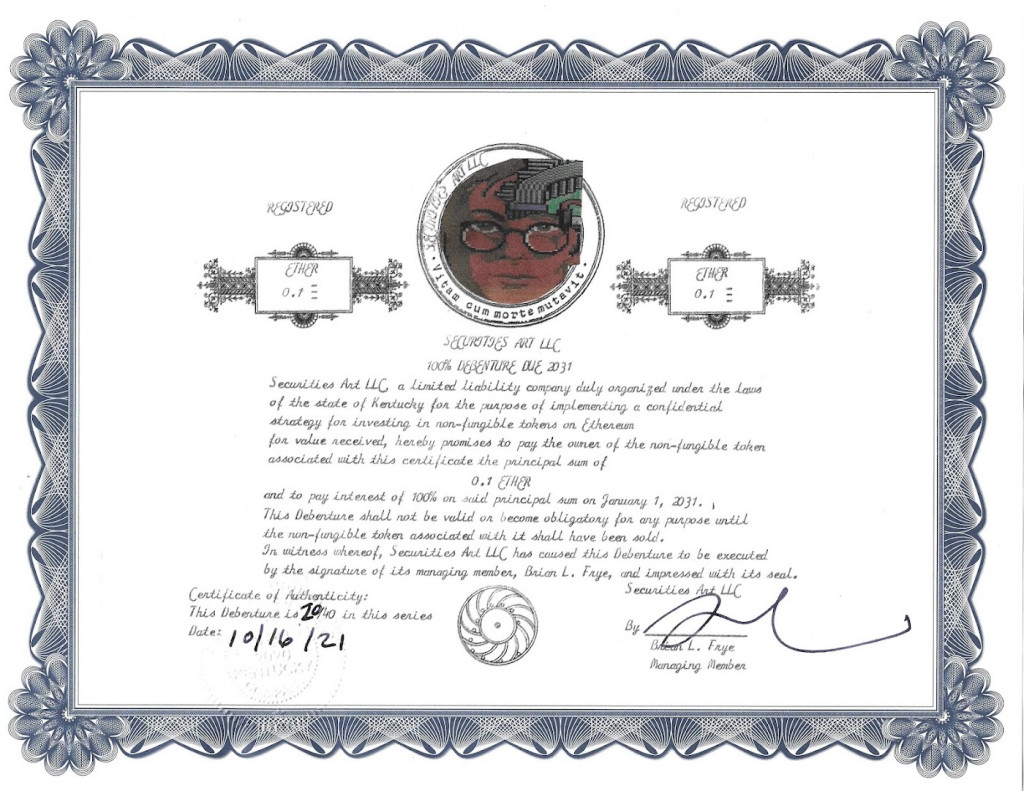

Philosophical questions about what exactly an NFT is—and what rights to ownership, use, and profit come with it—are unlikely to go away. For Christiane Paul, the NFT is best understood as “as an advanced digital version of a certificate of authenticity, combined with more evolved options for setting permissions to sell and collect royalties.” In a critical piece on DALL-E and the trend of turning AI images into NFTs, Kevin Buist suggested that “Perhaps the ease of minting AI outputs signals a dead-end definition of NFTs: a financial asset attached to a vaguely painterly image that has nothing to do with the rich human experience of making or standing in front of a painting.” Pushing in a different direction, Martin Zeilinger examined blockchain-based artistic projects in which the code outputs are treated as quasi-living beings, to suggest that NFTs might be considered as “autonomous computational agents,” “in which audiences are not in control of how they experience the work, and in which art-market gatekeepers lose their socioeconomic power over how the work circulates.”

The artist and lawyer Brian L. Frye argued that in their emphasis on digital property ownership, NFTs could render the concept of artist’s copyright obsolete: “NFTs created a new kind of digital scarcity that relies on clout, rather than control. Collectors value NFTs because they represent the prestige of ownership, copyright be damned.” In a conversation with the theorist McKenzie Wark, artist Rhea Myers saluted this development: “With an NFT, people who point out that you can right click and save the associated image—yep. Well done. That’s absolutely correct, and that’s a good thing.” Primavera de Filippi, although largely in agreement about “the value of maximizing the dissemination of creative works,” raised some reservations in a dialogue with Frye: “Copyright is not only about rewarding artists, it’s also about providing control over how your work can be used, displayed, or exploited commercially and non-commercially.”

This is only a partial overview of the topics broached so far—both in Outland and in the wider discourse on art and NFTs. In a constantly shifting landscape, there is always something new happening, something new to say. In twelve months from now, who knows which questions we’ll still be debating, and which we could never have foreseen? I look forward to finding out.

Gabrielle Schwarz is Outland’s deputy editor.