Fixing the Toxic NFT Brand

Jeffrey Alan Scudder has some suggestions for how to improve the negative perception of NFTs.

NFTs have penetrated the ivory tower. In the last week of September, a three-day conference on art and blockchain technology took place at Magdalen College in Oxford. Speakers and attendees from the distant realms of academia and industry came together in the Grove Auditorium, an elegantly appointed lecture hall that neighbors the college’s historic deer park. The event was also live-streamed, with remote participants beamed in via Microsoft Teams, their projected faces looming from the proscenium stage. Each day of the inaugural Oxford Blockchain, Art & Technology Conference—OxBAT for short—ostensibly took a different theme: art, followed by industry, and finally impact. In reality, the lines between these topics were either blurred or ignored, reflecting a reluctance to separate NFTs as artistic endeavors from their wider social and economic contexts. We are still discovering the contours of this new world, and working out how its parts fit together.

The tagline for the conference read: “Spreading the Wings of Encounter.” (The logo was a series of animated black bars that resemble a flying bat.) Flirting with mixed metaphor, the organizers said their aim was to “mov[e] beyond the silos” of different disciplines with a diverse—at times downright eclectic—line-up of speakers addressing each theme. Nonetheless, across all three days there were a number of familiar names from the art-and-technology events circuit. Two of the keynote speakers, Ruth Catlow of Furtherfield and the Economic Space Agency’s Pekko Koskinen, appeared at an NFT conference at the University of Kassel’s Blockchain Center in July. Catlow discussed the political potential of DAOs while Koskinen presented his theories on how game design can illuminate the workings of a tokenized economy. The other keynote speaker was the well-known artist Robert Alice, who set out a series of theoretical frameworks for how we might consider NFTs (“as speculation,” “as collaboration,” “as time,” etc.)

There is important work to be done to theorize art on the blockchain, but it needs to be communicated effectively.

Among the more unexpected contributions were talks on how blockchains might be used for the preservation of classic arcade games (day one), sustainable fashion (day two), and political campaigning (day three). These were given by a lecturer in creative media, a start-up founder, and a crypto professional, respectively. The propositions were thought-provoking, even if they could never fully satisfy the question of whether blockchains are really necessary for the projects under discussion—or whether they are simply a shiny new tool with lots of capital invested in them. The discussions also didn’t have anything to do with art. But they were at least easier to follow than some of the denser academic papers, on concepts such as the “mediality” and “iconicity” of crypto art and NFTs. The impenetrability was frustrating because there is important work to be done to theorize art on the blockchain, but it needs to be communicated effectively.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the talks that best held the audience’s attention came from people who are themselves steeped in the world of NFTs. Regina Harsanyi, who has spoken widely about the conservation and curation of tokenized art, explained why it’s a mistake to think of NFTs as a radically new art form. For Harsanyi, the longer history of time-based media art in museums offers vital lessons about how works should be documented, preserved, and displayed for artists and curators working with still-nascent blockchain technology. Kelani Nichole, founder of Transfer Gallery and head of experience at the new web3 platform E.A.T. Works, issued an impassioned critique of the ways in which NFTs intensify existing hierarchies within the art world while creating a host of additional problems. On the other side of the spectrum, and harder to take seriously, were the hype-filled platitudes about the NFT market and the devoted communities or “tribes” it fosters, from Devang Thakkar of Christie’s and teenage crypto sensation Benyamin Ahmed. A more balanced and practical contribution came from tax lawyer Izzat-Begum B. Rajan, who spoke about how laws and regulations affect NFT creators.

And what about these creators? Interestingly, certain artists and works came up in multiple talks, suggesting that a canon might already be emerging. Sarah Friend’s Lifeforms, Harm van den Dorpel’s Mutant Garden Seeder, and Simon Denny’s Backdated NFT/Ethereum stamp (all released in the foundational year of 2021) were particular favorites, illustrating discussions of the smart contract as an “agential being” and the temporality of blockchains. Conversations focusing on the market regularly invoked Beeple’s record-smashing Everydays: The First 5000 Days, the Bored Ape Yacht Club, and CryptoPunks. This highly selective sample was drawn on by crypto skeptics and advocates in equal measure. But space was given also to artists whose success has not been quite so stratospheric. A highlight of the conference was a panel discussion at the end of the first day, moderated by Jeff Davis of Art Blocks. Generative artists Amy Goodchild, Michael Connolly, Matt DesLauriers, and Wout Fierens weighed in on how NFTs have materially altered their lives and work, for good and for bad. “I used to hemorrhage money making art,” said Goodchild. “Now that’s completely turned around with NFTs.” And yet: “It changes the way I think about the projects I’m going to make and I wish that wasn’t the case.”

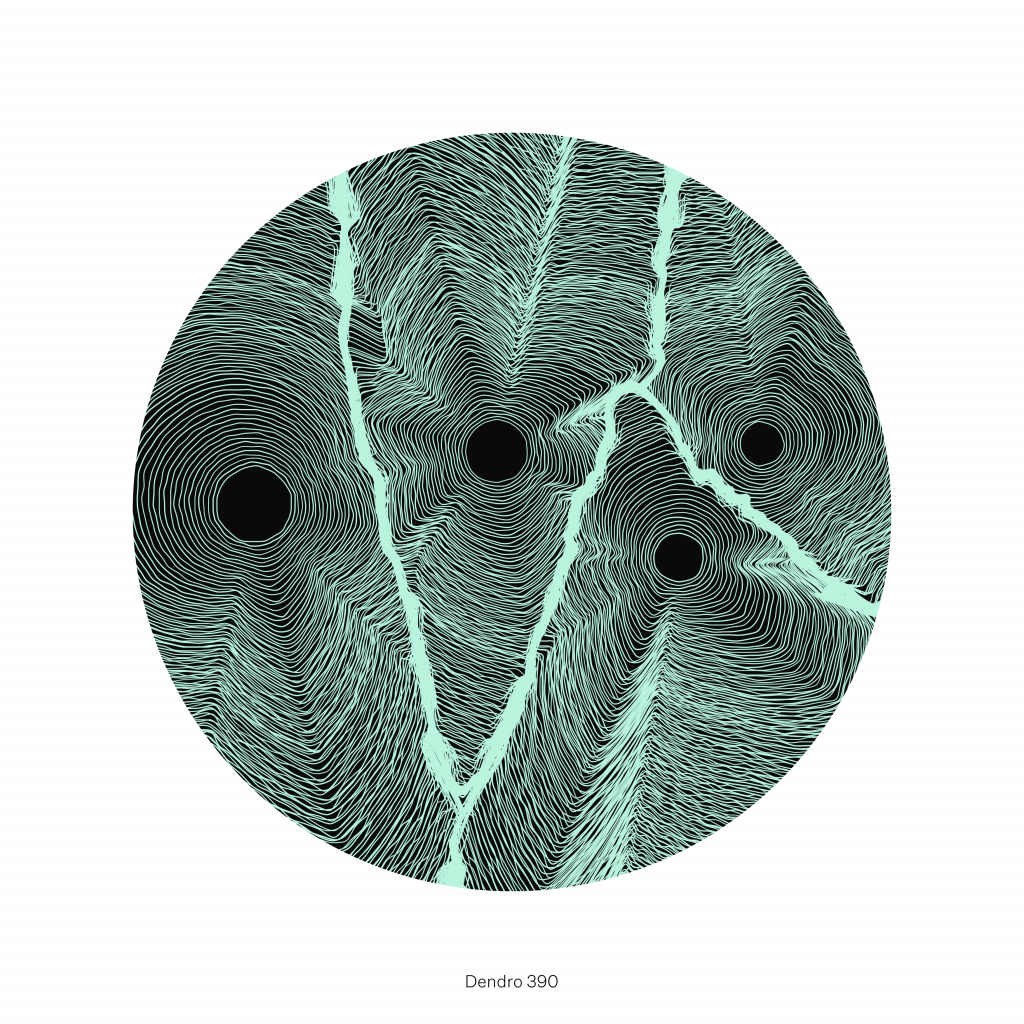

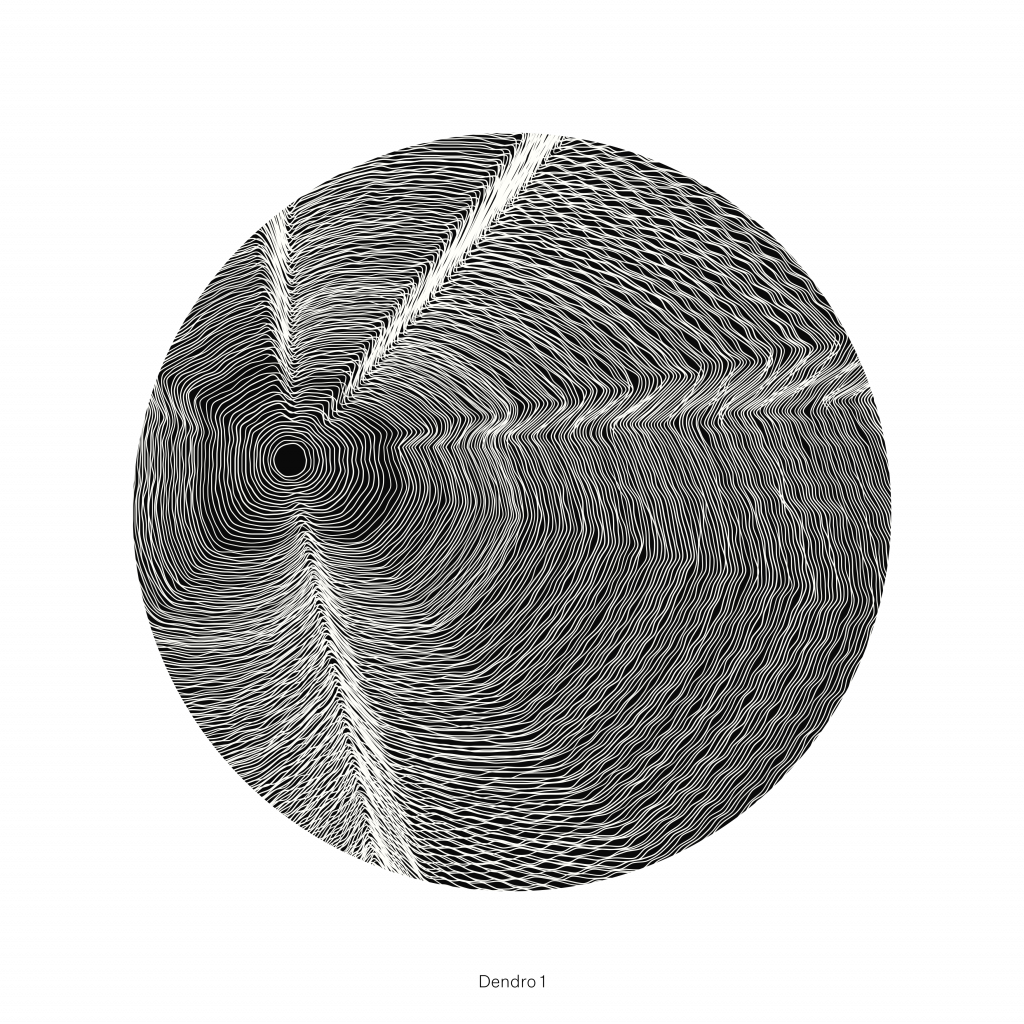

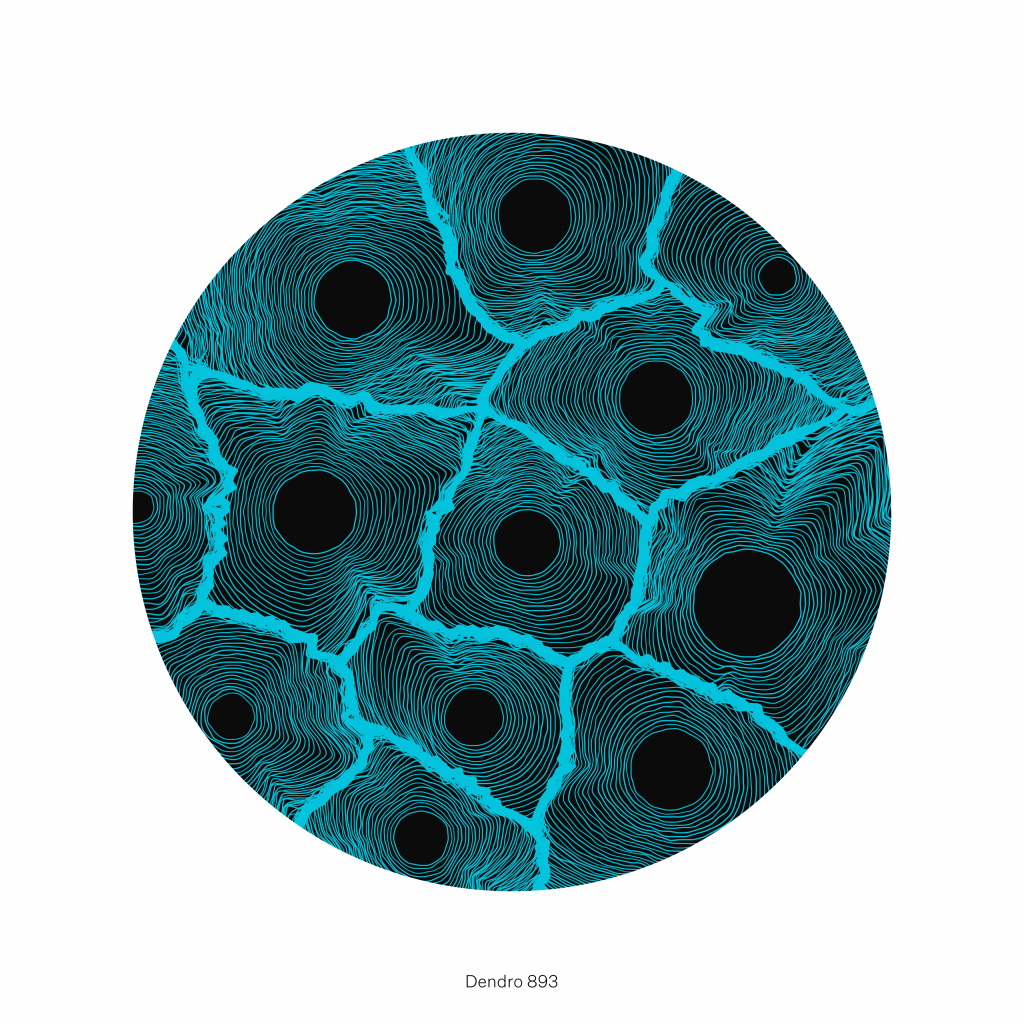

Between talks, attendees mingled outside the lecture hall in a foyer decorated with tapestries by the twentieth-century English artist John Piper (the space also contains a vitrine with a mammoth tusk discovered in the Magdalen deer park in 1922). On the walls below these hangings the OxBAT organizers had staged a mini display of artworks and projects relating to the blockchain. These included prints from Fierens and his collaborator Mick van Meelen’s recent generative art project DendroRithms, which imitates the growth rings of trees, and of DesLaurier’s colorful algorithmic mountainscapes. An interactive installation titled “A Token Gesture,” developed by researchers at the University of Edinburgh’s Institute for Design Informatics, invited users to mint their own free NFT of a digital artwork by Sasha Belitskaja. As well as serving a basic educational function, the “mobile kiosk” gathers data to understand audiences’ experiences of creating and owning NFTs.

People are still generally more interested in the world of NFTs than in NFTs themselves.

It was good to see these concrete examples of how blockchain technology has changed art—and vice versa. Somewhat disappointing was the fact that, at least from what I observed, very few people seemed to be paying attention to or talking about the exhibits. They had their business cards to exchange and elevator pitches to deliver. There were also no wall labels, or explanatory texts about the works, so it was difficult to engage with the display even if you wanted to. But perhaps the more significant reason for this indifference was that people are still generally more interested in the world of NFTs than in NFTs themselves. I don’t entirely blame them. As the conference itself proved, this is a world that while yet in its infancy has already given us a great deal to talk about.

Gabrielle Schwarz is Outland’s deputy editor.