web3's Creator Economy

In this week's news, developments in the web3 and NFT space continue to present new opportunities for content creators.

Earlier this month Art Basel released “A Survey of Global Collecting,” their report on art market trends, and my Twitter feed descended on the findings about NFTs. The survey of 2,709 high net worth art collectors—defined as those with wealth exceeding 1 million USD—found an average spend on art NFTs of 46,000 USD, which has gradually increased from 35,000 USD in 2019, when Art Basel’s researchers first reported on this category; meanwhile, 12 percent of respondents spent 1 million USD or more on art NFTs. The numbers provoked more questions than they answered. How was anyone spending so much on NFTs in 2019? Just how much of the averaged-out figure can be accounted for by that small minority of big spenders? Given the size of the NFT market, it’s obvious that the bulk of spending isn’t coming from HNW collectors. So who else is buying? What about NFTs has made digital art more appealing?

Similar questions were on my mind a year ago, when I was developing the editorial program for Outland: who is collecting NFTs, and why? I wanted to satisfy my own curiosity, and help others understand the shape of this new market. My solution was to conduct a series of interviews with collectors, in order to give people a platform for people to talk about the digital art they collect and why they collect it. Since Outland’s magazine launched in November 2021, we’ve published some forty-five of these interviews—including eight videos in the Groundwork series, featuring innovative institutional initiatives to steward digital art.

The art magazines I’ve worked with in the past never covered collectors, or did so rarely and gingerly, so that this coverage could not be confused with the critical appraisals that took up most of their pages. In art criticism, the market remains taboo, something only to be broached analytically, from a distance, not in personal terms. Art is the main story—not the people who own it. But when it comes to digital art, the appearance and growth of a new market is a major story. Furthermore, given the relative lack of expertise in digital art among critics, it made sense for Outland to highlight the perspectives of collectors who have researched the field and made considered decisions about what to acquire. Despite the dominant narrative of speculation—the notion that NFTs were bought solely as instruments for financial gains—I knew that some people were building collections for posterity. Of course, buying to hold and buying to flip aren’t mutually exclusive activities, as some of the collectors I spoke with frankly acknowledged; Blake Finucane, who wrote a master’s thesis on crypto art and now runs an NFT investment fund, said she uses “a different playbook” when investing as opposed to supporting artists whose work she loves. In short, there are hundreds of stories about collections of digital art, and I’m glad Outland has been able to spotlight so many of them. Because these articles feature individual voices speaking in the first person, there hasn’t been an opportunity yet to synthesize them. I’d like to take the end of the year as a reason to do so, and offer some qualitative findings to flesh out Art Basel’s quantitative ones.

A common refrain I heard when interviewing collectors is that the market for digital art offers more immediate access to artists than is available in the traditional market—and this often leads to greater involvement in shaping the environment for art. Pablo Rodriguez-Fraile said that he and his wife, Desiree Casoni, help artists with press relations and networking, “fulfilling the roles that other institutions play in the traditional art world.” He also launched a curated sales platform, Aorist. Ryan Zurrer is helping organize museum exhibitions for Beeple. Qinwen Wang, who curated an NFT exhibition at UCCA Lab in Beijing in March 2021, is working to enhance the culture around collecting by developing more ways for holders to enjoy their PFPs both physically and virtually, producing fine woven rugs for owners of Punks and Apes, and an app that verifies identity while maintaining the anonymity of PFPs. The founders of Refraction DAO took an inverted route. They already organized a festival of digital art and music, and got involved with NFT acquisitions to support artists when Covid made in-person events impossible. Their collection now supports an ongoing program of performances and exhibitions.

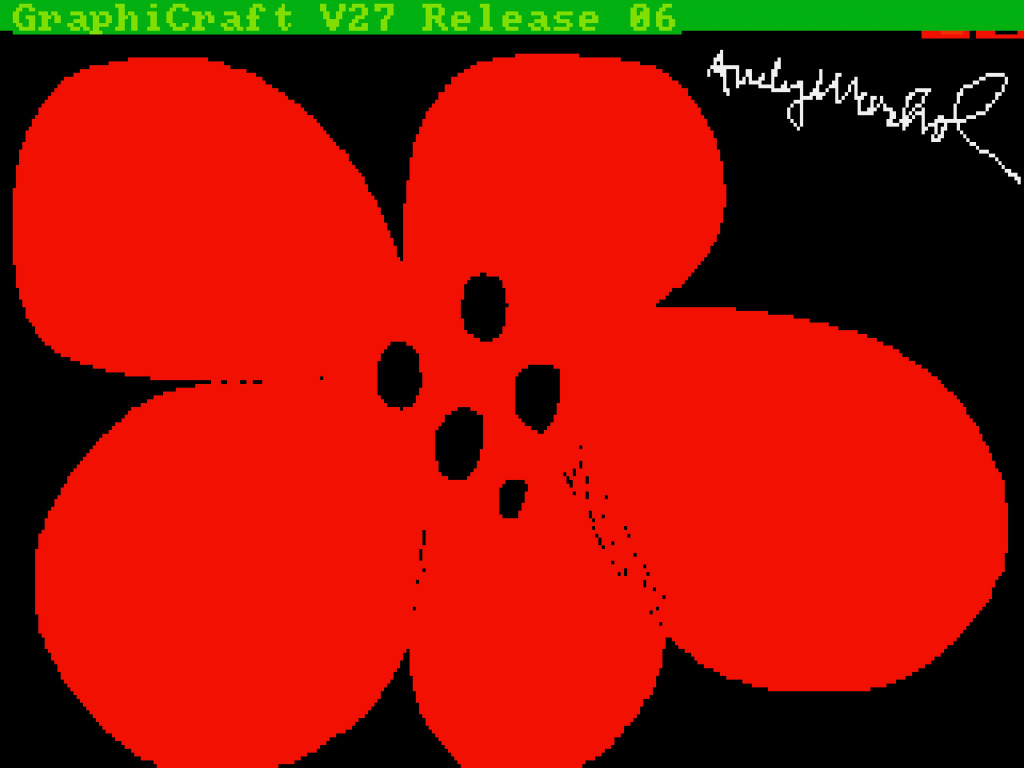

The novelty of the market means that collectors can make an impact simply by acquiring works with mutual affinities, thereby constructing a canon. A trio of Belgian brothers who operate under the moniker thefunnyguys have brought together significant generative art, from Art Blocks releases and experimental projects on fxhash to mints of older works by computer art pioneers like Vera Molnár and Herbert W. Franke. “Computer art has a long, rich history, and it’s important to me as a collector to continue to learn, while embracing those practices and communities that are furthering the medium today,” said one of the collective’s members. Jack Kaido, a pseudonymous artist who makes abstract digital painting, has built a substantial collection through his connections to artists who work in the same medium he does. He champions the value of “handmade” digital art, where artists create compositions one keystroke at a time, in a period when partially automated and randomized generative work dominates the market for digital abstraction.

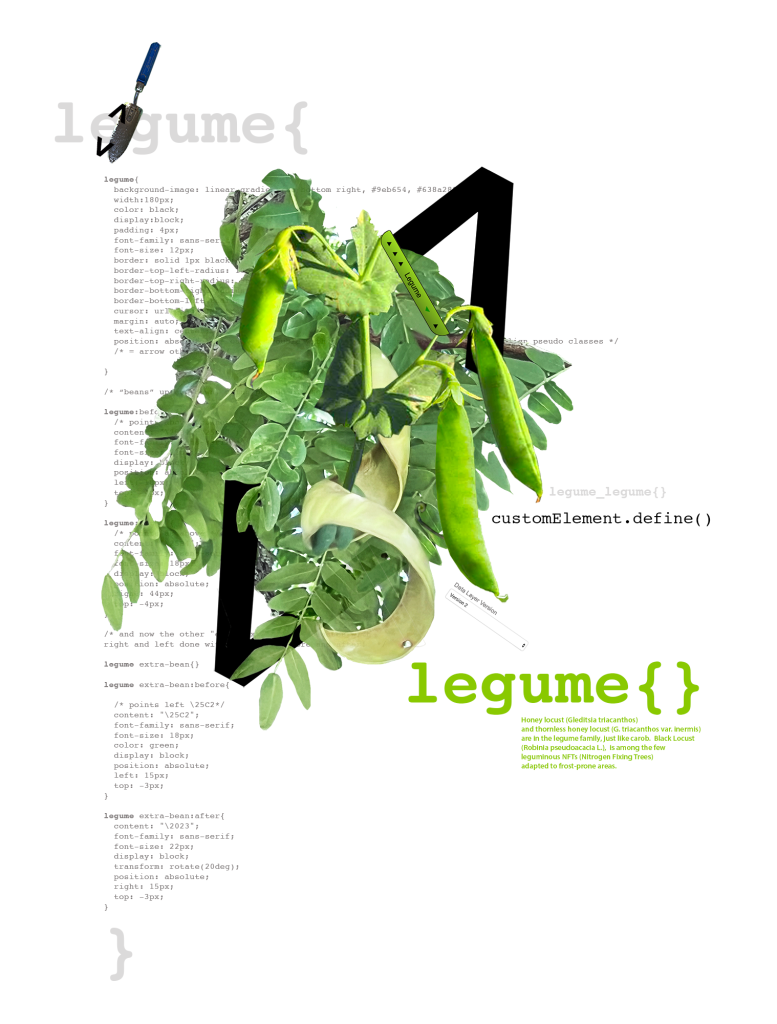

Nicolas Sassoon collects broadly, though like Kaido, he supports other artists whose approach is similar to his own, which in this case means highlighting the pixel as the fundamental element of the digital image. But for Sassoon, building a canon is secondary to building a new kind of art market. “I’m thinking a lot more about the sort of impact that artists collecting other artists have in that space, and the resulting circular economies,” he said. “In the twentieth century there were lot of attempts to redistribute money in the art world that never really succeeded. And suddenly there’s a window of opportunity with NFTs for artists to create circles of mutual support and gain autonomy and agency over their work.” His sentiment was echoed by other artists who spoke with Outland about their collections. “The act of collecting is a gesture of affiliation and support,” Michaël Zancan, a generative artist and prolific collector, said. Christopher Coleman, an artist and educator who has long supported digital art projects via Kickstarter and nonprofit fundraisers, emphasized the anti-elitist aspect of the NFT market. “To be frank, I’ve approached many of the famous galleries over the years to talk to them about acquiring works and they wouldn’t give me the time of day because I wasn’t a high-profile collector,” he said. Collecting on the NFT market has given him new ideas “of how an economy of digital art could exist.”

There is, however, still room for exclusivity and other legacy values. Jehan Chu, a Hong Kong-based collector who came to art through his work as a software developer for Sotheby’s, is confident that the chaos of the NFT market will eventually be subsumed into the art market and its mechanisms for establishing cultural significance. “The ambition of most artists is to be included in history, and traditional institutions—the museums and the major private collections—articulate that history, along with critics, curators, and art historians,” he said. “OpenSea doesn’t do that. Whales don’t do that.” There are also collectors who work in the classical mode of seeking out rare objects of historical interest. This approach is perhaps most common among “digital archaeologists,” who focus on tokenized art made before the advent of marketplaces such as SuperRare. White Rabbit is one such collector. He aims to map out an accurate history of art on the blockchain. “A lot of people will kick themselves for chasing the next billion-dollar 10K PFP project when all of that is a lot of fluff that will go to zero,” he said. “But the role these early tokens have played are locked in stone. They have a place that will always be significant.”

In an attempt to underscore how the increased prominence of digital art is broadly shifting attitudes toward collecting, I reached out to some interview subjects who don’t fit easily into any narratives of the NFT market and its development. I spoke to Peter Wu of Epoch Gallery, who mounts online exhibitions by asking artists to contribute pieces to virtual environments that he designs, then sells them as total virtual installations and divides the proceeds among the participants. Exonemo, the Japanese artist duo, only collect their own work, which often comments on the collector mentality and how it is adapting to the market for immaterial digital things. Arkive DAO is assembling a collection not of NFTs but of physical and digital artworks and cultural artifacts, using web3 tools to do so. They’re thinking about democratizing potential of web3 to reinvent the physical experiences of visiting exhibitions.

I also spoke with representatives of existing museums about collecting NFTs in the context of media art. “NFTs are not a form that arrived at our doorstep eighteen months ago, but inevitably participate in a longer history and community around digital art,” said Alex Gartenfeld, director of ICA Miami, which acquired its second NFT this year. “We’re interested in building a lineage of time-based and digital art.” At the same time, web3 is pushing institutions to rethink their relationship to the public in ways that go beyond collecting. HEK (House of Electronic Art) in Basel, Switzerland, has been building a collection of software art and net art for over a decade, and bought its first NFTs this year. Director Sabine Himmelsbach said she is working to establish a HEK DAO to involve a global audience in the institution’s decision-making process. At ZKM (Center for Art and Media) in Karlsruhe, Germany, exhibition technology specialist Daniel Heiss has been organizing shows and workshops to educate the public about blockchain since 2017. He also led an initiative to host a node of the Bitcoin blockchain—not to mine the cryptocurrency, but to support the network. “The blockchain is always said to be decentralized but when you look at the node counts, there aren’t that many,” he said. “Running nodes is an area where institutions can get involved and do their part in decentralization.”

The market for NFTs is not as hot as it was in 2021, and no one expects an upturn anytime soon. And yet some new releases sell very well, and the prices for some older projects stay high or rise. Speculative value has dried up in the bear market, but cultural value remains. The increasing interest in digital art from museums is a testament to the endurance of this value. But collectors still play a crucial role in identifying and establishing the digital art that matters as institutions work on catching up. What makes this space exciting is that collectors bring a variety of concerns and priorities: innovative uses of blockchains, craftsmanship with digital tools, artistic independence in a decentralized culture. Amid the consensus of digital art’s importance, the ways of valuing it are still being defined.

Brian Droitcour is Outland’s editor-in-chief